Letting nature be our mentor.

This is the first post in a continuing series on biomimicry.

Biomimicry is defined as learning from the genius of nature how to be gently and respectfully innovative. I will apply this to spirituality/wellbeing and to organisations such as faith communities in these posts. This is not new nor am I idealising nature- it’s simply something that is capturing my imagination recently.

“The genius of man may make various inventions, encompassing with various instruments one and the same end; but it will never discover a more beautiful, more economical, or a more direct one than nature’s, since in her inventions nothing is wanting and nothing is superfluous.” — Da Vinci

I first heard about peace silk on a trip to Hobart.

Walking through Salamanca Markets on a bright-blue-sky, cold morning I stopped at a stall selling wild silk scarves. Anything with wild as an adjective attracts my attention these days so I reached out to touch the cream coloured scarf. It felt rough in my hands. Not what you usually think of when you imagine silk. I think “silky- smooth”, polished, shiny and expensive. I also think exotic- the silk roads- dreamy and evocative but also mercenary and colonising.

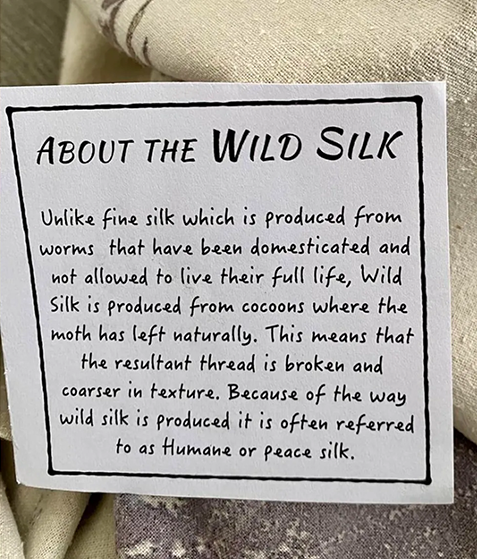

A tag explained that wild silk is sometimes called “peace silk”.

It led me on a journey to exploring the silk-making process. As always when you start looking into things you don’t know anything about, you discover that processes are often riddled with disturbing practices. Sometimes they border on unethical, occasionally they are cruel and frequently revealing how hungry we consumers are for “more stuff” at other’s expense.

Silk worms as it turns out are domesticated and bred to spin their cocoons then their natural life is cut short- they are killed so that the beautiful, smooth fabric we call silk can be made. However, wild silk allows the silk worms to live a natural life “where the moth has left naturally”. As a result, the silk produced is rougher.

That’s why as I held the silk in my hand it did not feel like what I usually imagine when I think about silk but rather I was aware of something more raw, tough and yes- wild. I liked the way it felt even though it was unfamiliar.

It made me think about the tension between domestication and wilding- a live discussion for decades now in farming, food production and care for our planet.

What does it mean for an organisation to become “wild” rather than domesticated? I’m thinking about this as applied to the growth of small faith communities that refuse to work within the usual system of institutional structures. In other words, they resist being domesticated, tamed and cultivated by an external framework seeing this as restrictive and perhaps even oppressive. Like the domesticated silkworms who are capitalised for our consumption, these faith communities that often fly under the radar feel that in order to survive they need to break out of that system- or at least work their way around that system.

How can the system and these free-range faith communities work together? Even the peace-silk produced from these glorious yet mostly doomed moths requires human intervention and an intentional process in order to produce the beautiful, textured and carefully dyed fabric that I held in my hands on that day in the markets.

I love the idea and practice of wild silk or peace silk. It feels right and good, natural and uncomplicated. I also love faith communities that are experimenting to do things differently. We need them and I suspect that most of us long to be part of these kinds of communities. How can the wild and the domesticated work together to learn from and support each other so that we see these communities of spiritual well-being multiplying in our local spaces?

Karina Kreminski is the Mission Catalyst for Uniting Mission and Education

Photo by Dianna Cudworth from Pexels.com