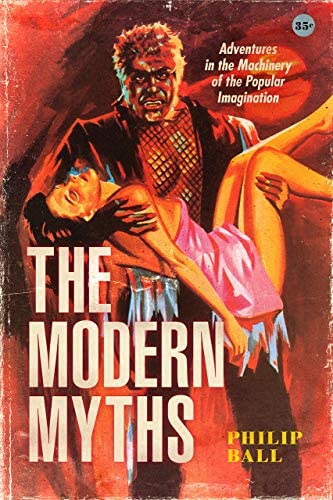

Review: The Modern Myths by Philip Ball

There are different ideas about what makes a myth exactly, but most agree that myths tell us something fundamental about human nature. We’re familiar with Greek myths, but Philip Ball wonders what more recent stories may have been elevated to mythic status, even if we might not think of them in those specific terms.

Ball, a writer on science, here ascends the cliff and climbs into the cave to wrestle with those unscientific, literary creations that have become embedded in our collective psyche, beginning with Robinson Crusoe. Although mythology is contested, Ball has firm ideas about what we should be looking for, and what a myth is not. A myth is a myth because of the story, not because of the qualities of the writing itself. Some of the modern myths Ball discusses aren’t written well – Robinson Crusoe, Frankenstein, Jekyll and Hyde, Dracula. The consensus of critics is that they are ‘messes’.

A moral tale of good and evil doesn’t automatically qualify, so sorry, Harry Potter, Star Wars and even Shakespeare fans. If you claim your story is myth, as William Golding did of Lord of the Flies, it is, argues Ball, merely a fable. Rather, a myth grows beyond the intentions of the author, is only a myth posthumously, and will speak to different readers in different ways, because meaning can never quite be pinned down. Myths help us think through questions without promoting definite answers, and this is why they keep cycling through our culture.

So, while Robinson Crusoe may reflect the individualism of the Romantic age, or the power of English colonialism, or even the modern reliance on reason, we might read it as showing how humans can’t live without society, no matter how resourceful. Ball also notes how the setting of Crusoe’s island has in the twenty-first century been transferred to the context of space, as in the film The Martian. Being marooned is scary, and while technology connects us, it also allows for the possibility of greater isolation.

Ball says the story of Frankenstein’s monster is the epitome of modern myth because it is ‘endlessly malleable’. While contemporary interpretations centre on the dangers of scientists playing God, Ball writes that upon the book’s release it was seen more as a criticism of the human hubris that led to the French Revolution – of the obvious dangers of the monstrous plebs. Obviously, it refers to the Greek myth of Prometheus, but even Mary Shelley can’t be relied on to explain her story’s meaning, and it has taken on a life of its own, if you’ll pardon the pun. Its power lies, says Ball, in Shelley’s humanising of the monster. This is no kraken or demon that is undoubtedly Other, but rather, because it (he?) is made of human parts, and we are even privy to the monster’s thoughts, the story raises uncomfortable questions about what it means to be human, and what constitutes life, issues that have become more critical for us dealing with AI and reproductive technologies.

Ball notes that the Frankenstein myth has been reinvigorated in Blade Runner and Terminator (Schwarzenegger recalls well the square-headedness of Boris Karloff), further reason to elevate it to mythic status perhaps. In the case of Blade Runner, the question is how autonomous human beings really are, and how programmed.

When a myth doesn’t have a genesis in a definitive and self-contained literary text, it is even more malleable. Look at Batman, whose story has been endlessly played with. Ball says that when we speak of Batman, we need to ask, which Batman? The Adam West Batman may be less mythical material, but we can see in the various Batman iterations an uncertainty about his character and motivations (in contrast to Superman, who, Ball reminds us, is pretty one-dimensional, let’s face it, as well as being, we might add, not human anyway). If we are thinking of the Dark Knight, the point, if we can pin one down, is that we have an uneasiness over whether darkness can be defeated without becoming dark ourselves, and an uneasiness over confronting what darkness might lie within us.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.