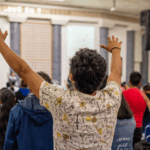

Today, on this 75th anniversary, we remember past events … we mourn the lives lost and grieve for the lives damaged and distorted … and we hear the invitation to commit to seeking peace in our own times.

75 years ago, on Monday, 6 August, 1945, at 8:15 am, a nuclear weapon which had been given the ironic name “Little Boy” was dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. The bomb was dropped from an American plane, the Enola Gay.

Three days later, on Thursday 9 August, 1945, at 11:01 am, another nuclear weapon was dropped from another American plane, the Bokscar, onto another Japanese city, Nagasaki.

The two bombings killed a number of people, variously estimated between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and impacted the lives of hundreds of thousands of people for decades. It is estimated that between 90,000 and 146,000 people died in Hiroshima and 39,000 and 80,000 people died in Nagasaki; roughly half of the deaths in each city occurred on the first day.

Despite the high military presence in Hiroshima, fewer than 10% of the casualties were military personnel. In Nagasaki, only 150 Japanese soldiers died on the day of the bombing. Over 90 percent of the doctors and 93 percent of the nurses in Hiroshima were killed or injured—most had been in the downtown area which received the greatest damage.

Many people lived with the traumatic memory of those days, and grieved for relatives and friends who died. Many suffered terrible illness, physical disfigurement, or mental illness, for decades after those bombs were dropped. The personal and social impact was huge. Had this been considered before the bombs were dropped?

Winston Churchill (right) and Franklin D. Roosevelt (centre) in Quebec in 1943, hosted by the Canadian prime minister William King (left)

The United States was not solely responsible for these bombings. Under the Quebec Agreement, the US had to seek the consent of the United Kingdom for such an action. The Quebec Agreement was a secret agreement between these two nations, setting the terms for the coordinated development of the science and engineering related to nuclear energy and nuclear weapons.

The Quebec Agreement was signed by Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt on 19 August 1943, in Quebec City, Canada. These bombings had been intentionally planned and deliberately prepared for over the course of the two years prior to August 1945.

Hiroshima was a supply and logistics base for the Japanese military. It was a logical target for American aggression, as it was a centre for communications center, a key shipping port, and an assembly area for Japanese troops. It contained manufacturing plants in which were made parts for planes, boats, bombs, rifles, and handguns.

Nagasaki was one of the largest seaports in southern Japan, and was of great wartime importance because of its wide-ranging industrial activity. It had manufacturing plants which produced ships, military equipment, weapons, ammunition, and other war materials. The four largest companies in the city employed 90 percent of the workforce: Mitsubishi Shipyards, Electrical Shipyards, the Arms Plant, and the Steel and Arms Works.

The strategic logic in targeting these two cities is clear. The city of Kokura had been the primary target for the 9 August bombing, but clouds and smoke drifting in from the Allied bombing of nearby Yahata, resulting in much of the city Kokura being covered, obscuring the aiming point.

The bombings had the desired strategic effect within the war that was being waged; on 15 August Japan surrendered to the Allies, and on 2 September the Japanese government signed the formal instrument of surrender.

Was the terrible cost from these two bombings worth it? In terms of military strategy, undoubtedly so. In terms of the overall picture across the world, torn asunder by a vicious war, it may well be possible to see the benefits of ending the conflict, even in such a dramatic way.

But the personal and social impacts of these two bombings set up severe consequences for hundreds of thousands people over the ensuing decades. The social fabric of Japan was shredded. The military hubris of the Allied powers was nourished and encouraged.

And the political consequences of these two bombs was that nations continued to distrust each, and to relate to each other in antagonistic ways, fostering secrecy, promoting public dissembling and posturing, generating a game of threats and power plays across the ensuing decades. The US threatened many times to make use of the superior nuclear firepower that they claimed—although, thank goodness, they did not ever act on that. But the public threats and bluffs continued apace for years.

Perhaps the one enduring benefit form these tragic events was that the nations of the world, despite this public braggadocio, did become very cautious about how nuclear power was used. No similar nuclear bombing or other large scale nuclear weapon has been used in warfare since then, probably because the devastating impact of these bombs was registered around the world, and a firm commitment was made to avoid such large scale and widespread devastation.

What lessons can we take, 75 years later, from these events? We can seek ways to interrupt the course of injustice, without adopting the means of injustice that is being experienced. We can seek to combat evil without adopting the patterns of evil. We can nurture a response that is neither fight not flight, but rather, seeking reconciliation and justice in all we do.

As we do this, we follow the way of Jesus, the prophet of old who speaks words for the present, blessing those who live out the qualities that he most valued:

Blessed are the poor in spirit. Blessed are those who mourn.

Blessed are those who are hungering for righteousness.

Blessed are the pure in heart. Blessed are the peacemakers. (Matt 5:3-12)

And as we follow this way, we seek to live as his followers proclaimed, pursuing what makes for peace (Rom 14:19; Heb 12:14; and see Gal 5:22; Eph 6:15; 1 Pet 3:11).

My colleague Chris Walker writes: ‘Let us then be peacemakers following the way of Jesus. Jesus himself rejected the way of the sword. At his arrest he told his disciples to put away their swords. He followed the way of suffering love and did not resort to violence. Even on the cross he cried out, “Father forgive them; for they do not know what they are doing” (Luke 23:34).’

War causes such pain, such turmoil, such hurt, such dislocation. It has ongoing and enduring consequences. It might solve an immediate problem, but it inevitably sets up longer term dilemmas, difficulties, and discords. War can never bring deep, enduring peace.

To be sure, going to war is seen by many as a legitimate way to resolve disputes and solve arguments, on a large scale. There have even been, through the ages, sophisticated arguments mounted to justify warfare. Fighting evil is seen as essential. War is reckoned as the way to do this.

But war has many consequences. It damages individuals, communities, societies, and nations. It has many more innocent victims than the casualty lists of enrolled personnel indicate. And there is abundant evidence that one war might resolve one issue, but often will cause other complications which will lead to another war. Look at the outcome of the Armistice at the end of World War One: we can trace a direct sequence of events that led from World War One to World War Two.

Sometimes, pitched battle warfare seems to be the only possible way forward. Yet, overall, a commitment to peace is surely what we need to foster. An aversion to war is what we need to develop. A culture of respectful disagreement and honest negotiation, rather than pitched rhetoric and savage violence, is surely what we ought to aspire towards.

Can that be the commitment that we make, today, as we remember the tragedies of 75 years ago?

For this anniversary, the Uniting Church has joined with many other religious organisations, calling for a full nuclear weapons ban—for Australia to sign and ratify the 2017 UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

John Squires is the Presbytery Minister (Wellbeing) for Canberra Region Presbytery. This piece originally appeared on his blog, An Informed Faith.