Review: Streeton, Wayne Tunnicliffe (ed.), Thames and Hudson/AGNSW

It’s summer, and Arthur Streeton gets a blockbuster exhibition at the AGNSW, and a big, accompanying, hardcover catalogue with just one word on the cover: Streeton.

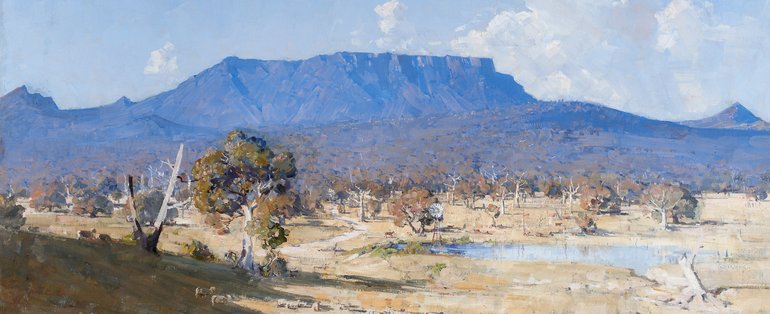

Setting aside Indigenous artists for a moment, who else’s paintings are more iconically Australian, more able to convey the heat and light of the Australian summer? Brett Whiteley? Too racy and Sydney-centric. Arthur Boyd? Too mythical. John Olsen? Too messy. Hans Heysen? Well, he sure could paint eucalypts. Sidney Nolan is a contender simply through his use of the iconic Ned Kelly. Streeton’s fellow Heidelberg School artist Tom Roberts has painted some iconic Australiana, but Streeton is a master at the sweeping landscape – pastoral Australia in the Nepean, Melbourne outskirts and Victoria’s Western District, the Blue Mountains, Sydney Harbour. As the catalogue tells us, he was a savvy businessman, knowing that there was a market for these vistas, appealing to both those who worked the land and those in the burgeoning cities. But his was also a passionate response to the landscape.

It’s a truism that art pushes boundaries and eventually becomes the establishment. Streeton followed in the footsteps of the European Impressionists in being criticised for the looseness of his brushstrokes and indeterminacy of objects in his early paintings. He and his fellow artists wore the criticism as a badge of honour, and from our perspective the style now seems to suit the haziness of our environment. There was also a desire within the Heidelberg School to paint what they saw, en plein air, as the Impressionists did, without the contrived conventions of framing devices and the like that previous landscape painters had used. In this, they had the attitude that the Australian countryside was interesting enough without needing to ‘improve’ the view, a quite modern revolution.

Streeton didn’t like modern art of the likes of Cubism, and certainly by the end of his career his art seemed old-fashioned compared to some of the stuff coming out of Europe and the US. But his hasty oil sketches, where the point was capturing simply light and colour (in his famous blues and golds), as well as being comparable to Turner, have parallels with artists working in the later Abstract Expressionist tradition, and in many Australian landscape painters today we see the desire to evoke feeling rather than accomplish exactitude.

His art was not necessarily nostalgic – his Sydney paintings document the rise of apartment buildings, and his harbour paintings feature the smoke of tugs and steam ferries. (Streeton loved painting Sydney, for its endless possibilities of outlook and contrast of land and water.) But he worried about the retreating bush. A painting was entitled ‘Our Untidy Bush’ approvingly, I assume. And paintings of felled forest and timber milling usually contain an air of criticism. In one of the catalogue’s essays, Tim Bonyhady describes Streeton as something of an environmentalist. In 1939 and 1940 he painted an unusual pair of pictures of the Dandenongs in Victoria, one of which was his dystopian vision of what the countryside would look like in 2000 if clear-felling continued.

A painting such as ‘The Land of the Golden Fleece’ (a subject, in fact, which he painted and reworked a number of times) suggests, typically for those of a European background, that the countryside – in places – was perfect for the pastoralism of sheep and cattle, rather than the Indigenous country explorers and settlers encountered. Who knows what Streeton would have made of recent Indigenous art? But here is a richer, older and more appropriate vision than the colonial one, and one that has increasingly, thankfully, been embraced by the wider Australian community, even if we still have a long way to go. And yet in Streeton’s art, the book suggests, we see a sympathetic, holistic and pioneering view – a step on a journey of appreciating the land for what it is and recognising the need to conserve it.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com