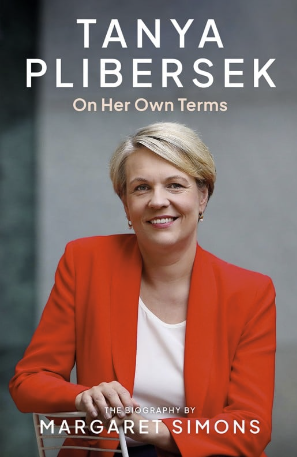

Review: Tanya Plibersek: On Her Own Terms, Margaret Simons, Black Inc

Tanya Plibersek is a big Jane Austen reader and identifies with Sense and Sensibility’s Elinor Dashwood, the responsible and sensible elder sister. Regarded for what Plibersek herself calls her ‘coolness of judgement’, she also knows she can be emotional, driven by a sense of needing to help whomever she can, whenever she can, a trait cultivated in her childhood by her immigrant parents.

Joe and Rose Plibersek have a somewhat typical migrant story. They are from Slovenia originally, where there was the usual post-war chaos and hardship. Joe worked on the Broken Hill railroad, then the Snowy Hydro, before meeting Rose and settling in the southern Sydney suburb of Oyster Bay, in a time of booming suburbia and accompanying prejudice.

Not surprisingly, in hindsight, Plibersek excelled at school, especially debating, and friends said she would be a politician. From a young age, the ideals matched the skills – family and friends recall her early engagement with thinking about right and wrong in the world. At 15 she joined the Labor party, as it seemed to embody politically her family’s values of helping those in need.

If anything becomes monotonous in Simons’ book it is Plibersek’s unflagging energy for helping others, including in her local constituency, despite her demanding federal position. Simons notes how, as she rose as a politician, staff had to explain that she didn’t have time to sit for hours with every person of need who came through the office door.

In federal politics she has had to compromise. As a teen, she studied journalism at UTS, where both major parties were suspect. She soon quit Labor over Hawke’s nuclear and Aboriginal policies, which weren’t radical enough for her. But she says she learned in politics that you can’t ever get 100% of what you want, and getting things done is a matter of negotiation (an attitude Penny Wong, another of Simons’ biographical subjects, also holds). This has clearly helped Plibersek survive politics both within and outside Labor.

She worked in the public service department dealing with domestic violence. When she couldn’t get enough traction there on the issue, she joined Labor again, to try and advance the position of women, especially those in difficult circumstances.

As a minister, she has worked on issues of homelessness and childcare. After the GFC she was involved in a successful housing scheme, which put homeless people into homes, an example of practical, life-changing government action she cherishes (in contrast to the Howard government’s largely ineffectual ‘leave it to the market’ philosophy). She describes herself as a persuader, someone who wants to get the job done right. (We need long-format political writing like Simons’ book because such successes are rarely mentioned in the mainstream media, where politics is often a matter of soundbites, scandals, personalities and machinations.)

Her kids say she cries at the drop of a hat. And she can be fiery – she had to apologise for personal barbs at Peter Dutton – but she has a reputation for competence and kindness. Her husband says her ability to stay calm under pressure is ‘infuriating’. But this is seen as an impediment to becoming PM – some see a lack of ruthless political ambition and vision.

Maybe that’s because she lived through a ‘toxic’ period of Australian politics: Howard’s wedge politics, Labor’s ever-revolving leadership of lacklustre Crean and Beazley and the unhinged Latham, then the backstabbing and car wreck of Rudd/Gillard/Rudd. Characteristically, after having seen the Rudd/Gillard era up close, she is wary of a cult of personality, of the search for the charismatic saviour, and sees governing as a team job. (But then, a politician would say that, right?) Additionally, she notes, as does Penny Wong, that as a female politician, she is still seen as abnormal, under more scrutiny than the men.

Plibersek was close to Albanese in their younger days, but, as they are from the same Labor faction, they inevitably became rivals. Now she says that her relationship with Albo (whose seat in Sydney borders hers) is ‘cool’. She remains a contender for leadership of the country, but a question that emerges from Simons’ book is: is she too sensible to take it on?

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.