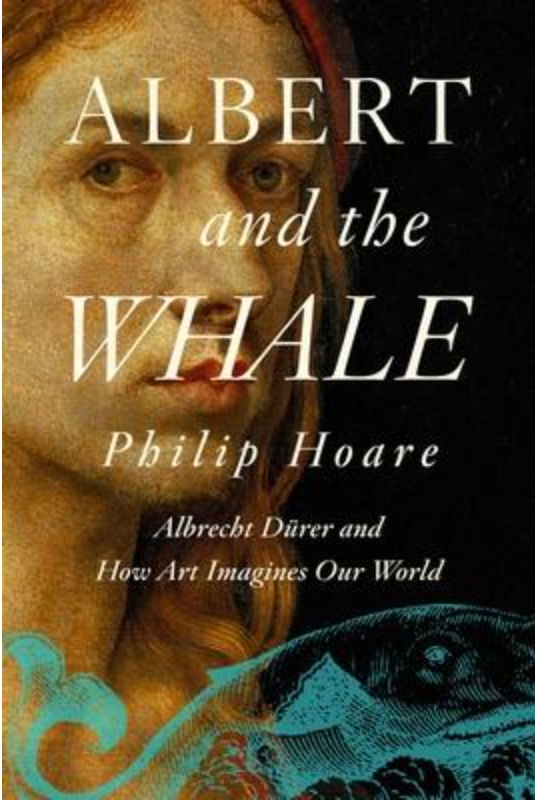

Reviews: Everybody by Olivia Laing | Albert and the Whale by Philip Hoare

The two new releases from British writers Olivia Laing and Philip Hoare similarly centre on an individual – in Laing’s case, European psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich; in Hoare’s case, artist Albrecht (Albert) Durer – but these figures loosely connect, in sometimes surprising ways, a cast of recurring, historical characters.

Laing’s book is subtitled ‘A Book About Freedom’ and she sneaks up on contemporary debates about freedom by way of an assortment of biographies of twentieth-century artists, writers and activists: Malcolm X, Nina Simone, Susan Sontag, Philip Guston, Andrea Dworkin, Agnes Martin. She writes about how they reacted to marginalization and notes that bodies can be vehicles for both oppression and freedom.

Reich, initially a disciple of Freud’s, who disagreed with Freud and was ostracized from Freud’s circle, worked on freeing the body from trauma, and this provides an overarching narrative. Some of Reich’s theories were odd, to say the least, such as his claimed discovery of the life force and his construction of a phone-booth style box for harnessing it. He also constructed a gun to control the weather and battle aliens. (Kate Bush, almost as kooky, wrote a song about it.) Laing is not convinced by all this but admires his dedication.

She doesn’t always agree with the radical feminism of Andrea Dworkin either, but places Dworkin in the context of women in the twentieth century trying to be free of submission, violence and the expectations of society. In turn, a reader may not always agree with Laing, especially when sexual freedom can sometimes seem like simple indulgence, but her writing is marked by her desire to understand, and by empathy with victims. As well as sexual and race politics, she writes about, in contrast to the superficial robustness of bodies as they are portrayed in the media, the way inhabiting a body includes dealing with illness and decline. She contrasts the ways Susan Sontag and Kathy Acker (whom she ventriloquized in her novel Crudo) dealt with cancer diagnoses.

Hoare’s book centres on Durer but he also writes on Durer’s biographers, novelist Thomas Mann, poet Marianne Moore and the Aztecs. Unsurprisingly, if you know his oeuvre, he writes about whales, that seemingly inexhaustible subject. Durer spent time on the Dutch coast, where whales stranded, but Hoare says he can’t tell us if Durer saw the whales or not. This didn’t stop Durer drawing them.

What Durer did see he drew with ‘almost uncanny’ precision. His drawings and paintings are wonders. No-one had painted nature like that before. John Ruskin told his students to try and emulate Durer but warned they wouldn’t get close. Hoare is entranced, lucky enough to have a private viewing of watercolours and etchings. He is gobsmacked and soon his writing is busy, words bumping against each other like images in a fever dream, echoing Durer’s almost obsessive, fecund details.

Durer lived in Nuremberg, later famous for its Nazi connections. Durer’s art survived allied retribution on Germany (not to mention disgruntled gallery-goers). Hoare holds a lock of Durer’s hair in a museum, but it is the art that survives better than the body. Hoare too writes of illness and decline – of Durer and Mann and himself. But what is remembered of Durer is the intense gaze of the handsome young man in the portraits. And, Hoare wonders, considering the threat of extinction that hangs over parts of the animal world, will Durer’s art outlive some of the animals he chronicled?

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.