Review: Has Archaeology Buried the Bible? by William Dever & Digging Deeper by Eric Cline

Archaeology and the Bible have had a relationship that has been both close and wary. In Has Archaeology Buried the Bible? William Dever says that in the nineteenth century one of archaeology’s purposes was to illuminate the Bible. For the British, he writes, this meant ‘illustrating’ the Bible. Americans had a more forthright attitude, using archaeology to ‘defend’ the Bible (possibly from European scholarship). By the 1980s the roles were reversed, and as archaeology trod its own path, the Bible was seen as useful by archaeologists only when it could further illuminate the finds of archaeology.

Dever is a former seminary student who gravitated to archaeology, and he says he takes a ‘middle ground’ approach. I would imagine he would agree with theologian Tom Wright, who has said that we have little to fear from scholarship of the Bible. Dever’s answer to the provocative question posed by his book’s title is ‘no’. In some cases, archaeology reinforces the biblical text, but then again, sometimes it makes us re-read and re-evaluate.

For example, Dever writes, Joshua and Judges contradict each other as to how exactly the biblical Israelites became dominant in Canaan and what happened to the ‘original’ residents. The evidence suggests that it was more a peasant revolt than invasion. Often the evidence points to shifts less dramatic and triumphant than some of the biblical stories. Archaeology also helps us to hear the voices of the poor, which are in the Bible but can be muted when the Old Testament history books focus on leaders.

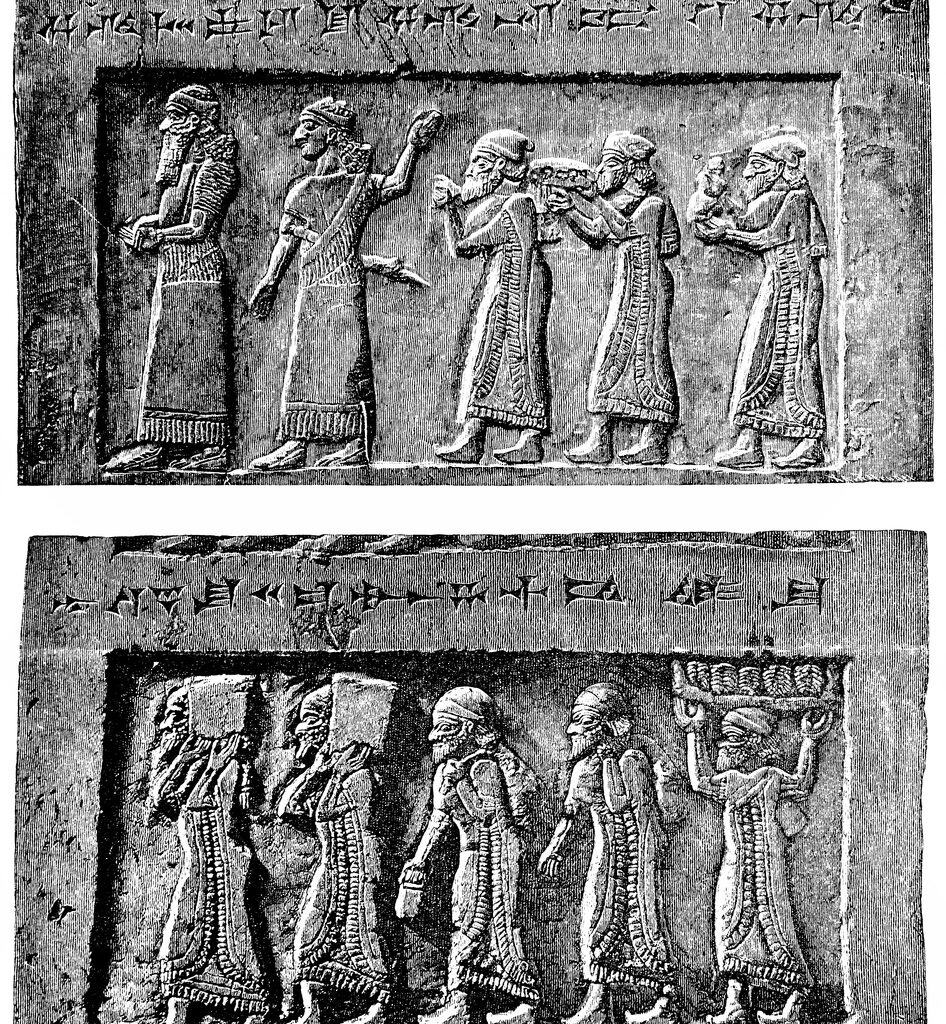

Events in the Book of Kings conform to archaeological evidence. There have now been more than a dozen temples unearthed in Syria, and they have similar floorplans to Solomon’s, as it is described in the Bible. But a book such as Judges, in conjunction with the archaeological evidence, gives us a better idea of the lives of villagers. Such things as when camels were domesticated challenge some of the chronology, but other finds confirm the nomadic lifestyle of Abraham’s descendants, which also explains, Dever notes, the nomad’s wariness regarding towns, an undercurrent of the story of Sodom and others. In his book Digging Deeper Eric Cline mentions that clay tablets found in the Middle East confirmed the Babylonian exile.

Cline’s is a little book about the practice of archaeology, similar to those in Oxford University Press’s Very Short Introduction series. He has excavated in Israel, particularly at Megiddo, where ‘Solomon’s Stables’ were found. (In the end, archaeologists decided they weren’t stables at all.) He writes about what to expect on sites, how sites are chosen, how they are laid out, measured, excavated and recorded. He writes about how artefacts are preserved.

He describes the importance of pottery styles for dating, but also says that context is important. Despite us being in what he calls the ‘Third Scientific Revolution’ for archaeology, refining aerial surveys and dating techniques, digging (and getting dirty) is still important. The correlation of artefacts in the layers tells archaeologists much.

He has a sense of humour and says that if his favourite trowel was found at a site, it would be classified as an antiquity. Short as the book is, he also moves beyond techniques to finds and their implications. Four-thousand-year-old mummies in China, in just one example, suggested surprising cross-continental travel, way before Marco Polo. Five-thousand-year-old Otzi the Iceman, found in the Austrian Alps in the 1990s, was so well preserved that a Czech professor could commission a shoemaker to replicate Otzi’s leather boots. (They turned out to be more comfortable than modern hiking boots.)

Cline finishes by discussing the problems of looting in the Middle East, particularly disastrous after the US invasion of Iraq and the actions of the Taliban and Isis, but also driven by the practice of private collectors paying big money for antiquities. Cline insists that ancient artefacts should not disappear into private collections but should be accessible to researchers, subsequently helping with the general public’s understanding of the past, even if, we might add, what is dug up may sometimes require a rethinking of what the biblical texts are telling us.

Has Archaeology Buried the Bible? and Digging Deeper are available now in bookstores.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.