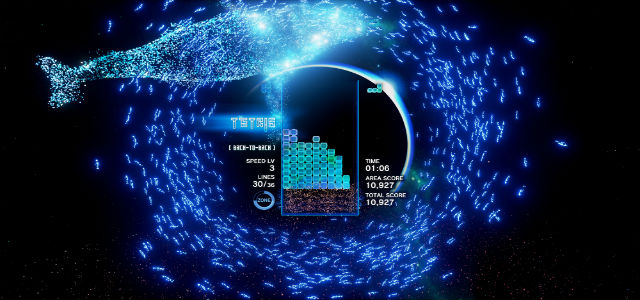

Earlier this year, I posted a short video to Twitter of myself completing a difficult level in Tetris Effect. Looking over the responses to the tweet, I was surprised at a common link between them: this footage of me rotating blocks into place, at high speed in a near-full Tetris basin, was stressful for people. All people saw was the challenge I’d overcome, and I hadn’t properly conveyed how it made me feel.

Tetris Effect, a Tetris game conceptualised and produced by the great Tetsuya Mizuguchi, is one I’ve sought a lot of comfort and relaxation from since it came out. Played at a high level, it’s difficult, but when you find yourself really in the ‘zone’, anticipating exactly where every block needs to go next, it can feel like being in the eye of a storm, a spot of calm amid the chaos of falling blocks.

Tetris Effect has been very good for my mental health during a trying period of my life. It’s not the first time a game has been important to my wellbeing, either; The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker lightened some very dark periods in my teen years, and numerous multiplayer games I’ve played over the years have facilitated and boosted important friendships and relationships. Words with Friends carried me through a period where I needed to stay social and active but did not have the mental energy or money to leave the house and see people. Mario Kart 8 is an important game for the bond I share with my younger sister; every time we catch up we run four races to see who comes out on top (last time, it was her).

The stats add up

It’s worth talking more about who plays games now, and what they take from the experience. Recently, the Interactive Games & Entertainment Association (IGEA) released the Digital Australia 2020 report on digital games use in Australian homes. 91 percent of households contain a gaming device, which is now defined broadly – any computer or smartphone counts. Of the 3228 individuals surveyed across 1210 households, about two thirds play video games. The average game player is 34 years old, and significantly, 42 percent of people aged 65 or older are playing games. These numbers are significant, and likely surprising to some.

The Digital Australia report, released biannually, isn’t just about who is playing games and what they’re being played on: it also digs into the ways games enhance the lives of those who play them. I spoke to Raelene Knowles, Communications and Member Services Manager for IGEA and Jeff Brand, the author of the report and a Professor of Communication and Media at Bond University, about their findings.

One of the most striking pieces of information to come from this year’s report, Knowles says, is that gaming is a social activity for most players: only 17 percent of people always choosing to play video games alone. “Games provide an important role in their lives by way of maintaining and developing connections socially,” she says. “The reasons people play is many and varied, but it is mostly to have fun, de-stress, pass the time, keep minds active, and be challenged.”

For Brand, the fact that so many people over 65 are now gamers is “astounding”, and bucks our standard perceptions of ‘gamers’. “This finding shows that games serve a purpose for young and old and that purpose changes as we age,” he says. “That flexible functionality tells me everything I need to know about the potential for games to have a positive impact on the lives of all people who play them.” Older gamers report that they play games, for the most part, to keep their minds active. The report also states that 47 percent of people playing video games in Australia are female, compared to 38 back in 2005.

Are there health benefits?

There are health benefits to video games, too, both mental and physical, and not just the games that encourage fitness (like Nintendo’s recently announced Ring Fit Adventure, a great-looking RPG that requires you to exercise to defeat monsters). Tetris Effect might calm me down, but it can have an even greater impact: Tetris has been used to ease psychological trauma and in treatment for patients with lazy eye conditions. Surgeons, too, are often encouraged to play games to improve their reflexes and practice complex procedures. “For many people, using controllers can treat chronic pain and may be useful in tackling arthritis, particularly in the fingers, but generally in the upper body,” Brand says. “We increasingly understand that varied movement is a significant predictor of mobility in ageing. We are also learning that playing can distract from pain.” The Digital Australia 2020 report states that 85 percent of people surveyed believe that games can help with their thinking skills, and 74 percent feel that they help their sense of emotional wellbeing.

It’s not just adults who benefit from video games, either. I’ve worked as the games editor for Mania, an Australian kids’ magazine, for nine years. I’ve covered hundreds of games for a young audience; I believe in games as a powerful tool to help children learn skills and solve problems, and that playing through a good game can be an important experience for a child, one that may shape their tastes and their sense of self going forward. I’m not alone in acknowledging how important games can be for children: educators and parents are now coming around to an activity that was once looked at as a distraction, and which is still vilified by many politicians and tabloids.

According to Jackie Coates, head of the Telstra Foundation and an online safety and digital parenting expert, “there are many upsides to online gaming” for kids. “Digital games can stimulate curiosity, imagination and focus and are often highly social with multiplayer options bringing friends together,” she says, although she also notes that “setting time limits” is a good idea. “I recommend a couple of hours max and avoid the all-nighters that some teens push for. This is an area you need to stay on top of and be consistent – make sure your rules are clear and enforced.”

Establishing rules is important

She also believes that establishing rules for proper manners in games is important: “don’t go idle in games or frequently drop out of multiplayer games, don’t team up against an individual or be over critical of other people’s playing styles or shortcomings, or crash into people on purpose if they are playing racing games.” Ultimately, she says, respectful young players can take much away from the experience. “Cooperative, multiplayer games can promote sociability and teamwork as kids play to solve challenges together and are often rewarded for their effective teamwork with others. In addition, role playing games can boost creativity, problem solving, and critical thinking skills, while console games can improve fine motor skills and hand-eye coordination.”

The Digital Australia 2020 report indicates that 59 percent of parents are now playing games with their children in the room with them (and 43 percent play online), and that 83 percent of parents are conscious of the safety of their kids in online play. Games are being used in the classroom more, too. “We’ve spoken to many teachers who find games are a powerful education tool, and in many cases they use ‘off the shelf’ games to engage their students, teach facts and create powerful learning experiences,” Knowles says. “Games often provide a safe place for kids to fail and as such encourage students to keep practising and finding alternative solutions to solving a particular problem or puzzle.” Brand says that he games with his own children: “If we play games with our children, we find joy in the connection and more control over their learning.”

The elephant in the room

The benefits to gaming are clear, then, but there’s an elephant in the room that needs to be addressed when we look at all of this: games culture has an undeniable toxicity problem. It’s not the problem Donald Trump and other fearmongers would have you believe when they say that violent games lead to violence, but there’s a history of developers being harassed, gaming personalities being excused for their blatant racism and sexism, and multiple cases of discrimination within the industry and the wider fandom. We cannot examine the benefits of gaming without also confronting this.

“We believe it is important that we empower players, parents and carers to play safely, healthily and responsibly,” Knowles says. “Industry does this via tools such as parental controls that allow parents to manage game time, suitability of game play and game spend, plus the classification system that provides easily recognisable guidance and advice to consumers on game content. There are numerous other fantastic resources that exist locally, but our single best piece of advice is to pick up a controller, talk to your child about the game and do your best to understand.”

Brand acknowledges that media isn’t neutral. “Countless studies have shown that how you scaffold and contextualise media determines their effect. We understand that some things tell us compelling stories about the challenges we face as a culture and species. Where those stories involve violence, we reflect on the many media that have represented mortal danger including the Bible, thousands of novels, thousands of movies, thousands of TV shows and thousands of games. How we consume these stories and experiences and how we are prepared for them is critical.”

But, he reiterates, it’s not anything inherent to the interactive nature of games that causes these problems. “The reality is that we scapegoat media, including games. Instead we need to leverage and use them. Find in them the experiences and messages that reinforce our values in the same way teachers make lessons from literature and religious leaders create moral teachings from religious texts.”

There’s more work to be done

There’s more work to be done on a cultural level to assure that video games can achieve their full potential as a force for good. The Digital Australia 2020 report suggests that the tired stereotypes around games being for loners, or in any way niche, are over, and now work must be done to make games as inclusive a space as possible. As games become not just mainstream but outright ubiquitous, the clear and tangible benefits they have to our health, wellbeing, and social lives mean that they’re only going to become more important for many Australians.

James O’Connor is a journalist and critic.