Since 2019 The Synod of NSW and the ACT has been supportive of the Statement from the Heart, and of the three elements of the Statement: Voice, Treaty, Truth. The Synod is, in principle, supportive of a substantive, constitutionally enshrined, Voice to Parliament. The Synod also supports the call for a Treaty (or Treaties) with First Nations, and of “Truth-Telling” about Australia’s colonial history.

In recent months there has been much discussion around the Statement from the Heart. The Prime Minister has publicly committed his Government to implementing all three elements of the Statement from the Heart: Voice, Treaty, and Truth. In particular, as a first step, Prime Minister Albanese has committed to implementing a constitutionally enshrined Voice for First Peoples via a Referendum, in this term of Government.

Australian Governments have had many opportunities to hear the Voices of First Peoples over many decades, through advocacy groups, Traditional Owner groups, Aboriginal organisations, and various Government Committees and Inquiries. Unfortunately, the broadly shared experience of Aboriginal peoples and communities, and our advocates, is that Governments have rarely taken this advice on board in any substantive way.

One only has to consider the 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody and its 339 recommendations: The ineffective, or non-implementation of at least a third of these recommendations to date, and the ongoing crisis of preventable deaths in custody of Aboriginal people 30 years on, demonstrate how easily Governments can ignore good advice.

The bulldozer-like implementation of the NT Intervention, contrary to the advice of several Aboriginal organisations and advocacy groups, which resulted in the punitive and discriminatory treatment of Aboriginal people and communities in the Northern Territory, and few (if any) positive outcomes, is another example of Government refusing to heed good advice.

What will a non-binding Voice to Parliament actually achieve?

Given this history, and the lived experience of Aboriginal peoples, many Aboriginal people ask a legitimate question: What will a non-binding Voice to Parliament actually achieve? The only way such a Voice can be effective is if the Government and the Parliament actually listen and act on the advice they are given… to be frank, history shows us that this is likely an unrealistic expectation.

While the current Albanese Government is possibly the most progressive Government this country has seen in terms of its stated commitments to First Peoples, this commitment has yet to be well-tested, and the cyclical nature of politics means that we will eventually see the return of a Coalition Government who, in my opinion, are unlikely to ever support a Treaty. We have not forgotten that in 2008 Peter Dutton MP, then opposition frontbencher, now Opposition Leader, walked out of the Rudd Government’s formal Apology to the Stolen Generations.

So why do some Aboriginal people enthusiastically support the idea of a Constitutionally enshrined non-binding Voice to Parliament? Maybe because “Something is better than nothing?”. Maybe because they genuinely believe the Government will listen to such a Voice? Maybe because they feel that trying to achieve a binding Voice, or a Voice that is envisaged in Article 19 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), is a bridge too far – perhaps too easily misconstrued as a “Third Chamber” by the likes of Malcolm Turnbull? Or maybe because a non-binding voice is considered a relatively easy win, and a first step on the journey towards Treaty and Truth Telling? Or perhaps a combination of some of these reasons?

In any event, the current Government has made a public commitment to implement the Statement from the Heart “in full”. I believe this means we will see a referendum at some point in this term of Government, on the question as to whether Australians support Constitutional change to enable a First Peoples’ (non-binding) Voice to Parliament. It may succeed. It may not.

The Voice is not the endgame…

Having spent significant time thinking about the Statement from the Heart, and in particular the usefulness of a non-binding Voice to Parliament, I recently realised something that has changed my perspective on the Voice issue. I had an epiphany of sorts. The Statement from the Heart has three elements, and the Voice is not the endgame. It is merely the pre-game entertainment. The Voice proposal is interesting, it provides some time for discussion (facilitating spaces for truth-telling), and allows us to prepare for the main event. In my opinion, the main event is the Statement from the Heart’s “Treaty” component.

Regardless of the non-binding nature of the Voice element, and regardless of the outcome of a referendum on whether the Constitution should be amended to enable such a Voice to Parliament, a Treaty can achieve any number of substantive outcomes such as acknowledgement of sovereignty, the return of land, mechanisms for redress, and so on. A Treaty could (and I believe should) also include a UNDRIP Article 19 type provision along the lines of:

The Australian Government, and all State and Territory Governments, shall consult and cooperate in good faith with the Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander Peoples concerned, through their own representative institutions, in order to obtain their free, prior and informed consent before adopting and implementing legislative or administrative measures that may affect them.

Self-governance and self-determination

In essence, an Article 19 type provision would enable all First Nations the opportunity, on a free, prior and informed basis, to have the right to consent (or not consent) to proposed legislation or administrative measures that may affect them. In practice, Governments would be required to properly consult with First Nations representatives and obtain their free, prior and informed consent to proposed legislation and administrative measures that are likely to affect them. The Voice can exist (if a referendum succeeds) to advise Government and Parliament on how to best develop legislation and administrative measures that are likely to impact First Peoples, while an Article 19 right would give First Nations, on behalf of their peoples, the right to effectively opt out of being subject to laws and administrative measures that are developed if those measures are deemed to be likely to have negative and/or discriminatory impacts on First Peoples. Such an ability to opt out is also a means of acknowledging sovereignty of First Peoples and providing opportunities for self-governance and self-determination.

Given the above, if the Albanese Government is committed to implementing the Statement from the Heart, in full, then the outcome of the Voice element is really neither here nor there – it would certainly be useful for the Government to have an elected Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander advisory body, but it won’t necessarily protect the human rights of First Peoples. On the other hand, any Treaty that acknowledges and reflects the benchmark human rights of Indigenous peoples contained in the UNDRIP, to which Australia is a signatory, must address the right of Australia’s First Peoples to have a say in the development of laws and administrative measures that are likely to impact them.

So I no longer feel the need to be concerned about debates about the Voice… Aboriginal peoples can support (or not support) a referendum for a Constitutionally enshrined (non-binding) Voice to Parliament without fear we are missing an opportunity to address the more substantive human rights of First Peoples. That opportunity will arise when Government addresses the Treaty element of the Statement from the Heart.

There is of course the question of whether the Government will ever get to the process of Treaty implementation? All I can say is that representatives of our sovereign Aboriginal Nations have been calling for a Treaty since we became aware of our entitlement to such an agreement, and the issue is never going to somehow just fade away. We now have an Australian Government that has named its commitment to enact a Treaty. The issue of Treaty is real, is on the table, and cannot be put back in the box. “Treaty” represents hope, healing and our way forward as a nation. It is not a matter of “if” we will see a Treaty, it is just a matter of “when”.

Nathan Tyson, Director, First Peoples Strategy and Engagement, Uniting Church Synod of NSW and ACT

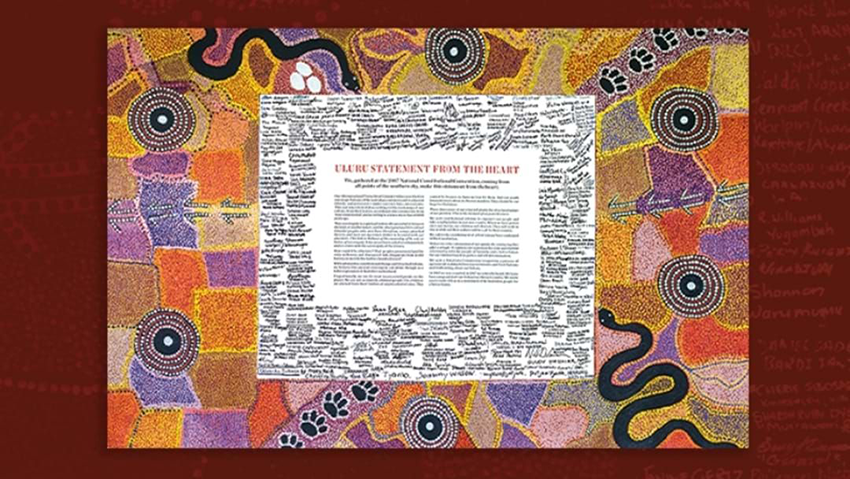

Photo courtesy of ulurustatement.org: In May 2017, over 250 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Delegates from all points of the Southern Sky

gathered in Mutitjulu in the shadow of Uluru and put their signatures on a historic statement.