Review: The Word: On the Translation of the Bible, John Barton, Allen Lane

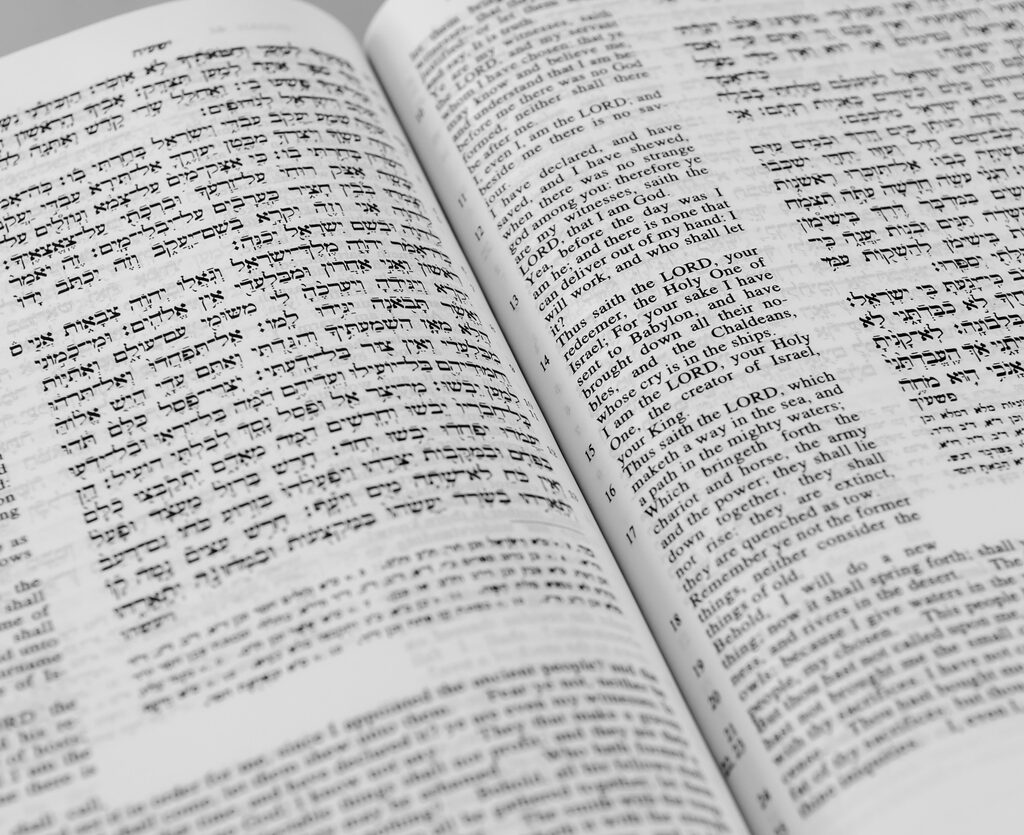

Translations can be good or not-so-good, or plain wrong, but they cannot be perfect. It is not so simple as just translating directly. Translators must make decisions. Good translation can be a balance or a compromise, depending on how you see it. This is exacerbated with the Bible. We are dealing with a collection of books in different genres, written in different languages, some of them already translations. (Jesus probably spoke Aramaic largely, but we know his words only from the Greek). And because the Bible is a religious text, considered sacred, the stakes are high.

This new book from John Barton, whose previous book was a history of the Bible, is consistently, enjoyably enlightening. It is concerned largely with translation of the Bible into English, but touches on French, German and Indigenous languages. The Bible has been translated into only (!) ten percent of around 7000 global languages, and of those, most have only one translation. English, on the other hand, has many, many versions of the Bible. And, as in many other areas, the twentieth century saw an acceleration of translation work.

Barton begins with a quick history of all this and then dives into the thorny issues. At the heart of translation is the purpose of the translation, whether that be theological or literary, which can set up a tension between readability and fidelity, although this may be too simplistic an opposition. Translations tend towards what are officially called either functional or formal equivalency. The former is concerned with how well the text reads in the destination language, whereas the latter is concerned with how closely the translated text aligns with the original.

There is no way around this – either it is more literal and takes more effort to read, or it is an easy read, due to some liberties being taken in the translation. Yet strict, word-for-word translations would make the text almost unreadable, especially because of the gulf between the grammars of Hebrew and English. Genre complicates this further. The explicit purpose of the 1923 Godspeed translation was to give each biblical book a distinctive voice, whereas most translations can be characterised by a distinctive voice or vocabulary across all the books.

A primary purpose – but not the exclusive one – of biblical translations is to spread the Gospel message, but this can create some tension between fidelity and readability, and is more complicated than it might seem. The Good News version uses deliberately simple language, for a wide readership, but this entails a loss of sophistication of theological argument at times, as in Paul’s letters.

When translators have had evangelism front-and-centre, they have sometimes tried to make cultural references more relevant for the intended audience, such as referring to bananas rather than figs for Pacific audiences. Translations like this can tip easily into paraphrase, which aims to get across the gist, in accessible language, while largely eschewing word-for-word agonising. Eugene Peterson’s The Message is the most prominent recent example.

As Barton puts it, a translation always reflects its times. Language evolves, so translations date. J B Phillips made an accessible translation for his time, but it is now dated by the way he, hilariously, substitutes ‘hearty handshake’ for ‘holy kiss’. Aussie slang versions of the Bible may be a bit of a joke and cringe-worthy, and also date quickly. But maybe that’s okay, as colloquial translations need to be updated every twenty years or so anyway. The inclusion of inclusive language in the NRSV is yet another, controversial example of contemporisation.

The influence goes both ways, as we know from the influence the King James Version has had on

English. The Luther Bible did the same thing, unifying the German language. (Germans got an updated version for the recent Luther anniversary.) Cyrillic was invented for the purpose of being able to write down a Slavic translation.

Although the argument is sometimes resisted, a translation cannot help but make theological interpretations. Jews and Christians interpret the Bible differently, and the choice of words reflects this. A key area is the supposed foretelling of Jesus in the Hebrew Bible’s prophetic works. (This Christian interpretation is heightened by the wrong assumption that ‘prophetic’ in this case means predicting the future.) The NIV is, famously, translated through an evangelical lens, and the translators made choices in, especially, the words they used to reflect theologies of atonement and justification by faith.

There may be differences of theology between the biblical books too. Paul’s understanding of faith is likely different – more individualistic – than that of writers of the older texts he refers to. Then again, there is an argument for intertextuality – for meaning coming to us modern readers via the way all the texts talk to each other. This aligns with postmodern literary theory, but it is also the Jewish midrash way of interpretation.

Jewish translations tend to be, unsurprisingly, more concerned with the text’s relationship to Jewish culture. At their most passionate, advocates of this way argue that taking the Hebrew and thoroughly demystifying it in everyday English speech is a form of cultural theft, a deliberate minimisation of the culture that is inseparable from the text. Robert Alter has made recent translations of the Hebrew Bible and deliberately uses what may seem surprising word and syntax choices, in order to keep the text(s) seemingly exotic to English readers.

One might think the text will have less impact if the language is not so familiar. But there is an argument that a more formal or irregular English translation makes us pause, removes familiarity, makes us think more about what on earth it means, as well as making it seem more sacred. Yet this may not make sense as a blanket argument – the fact that there are multiple genres of biblical books might mean that some are by nature more accessible than others. Some biblical books may best reflect the language of the court, others the language of the pub. Even then, says Barton, we have to be careful of assumptions: Paul’s letters, say, may seem informal, but that is not necessarily the case. They are quite legal in places and were not just dashed off quickly.

Barton, for what it’s worth, tends to like a bit of formal language, to give some sense of distance between modern readers and the biblical world. Taking into account personal preferences may sometimes be beyond translators, but it is another indication of how loaded the translation process is.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.