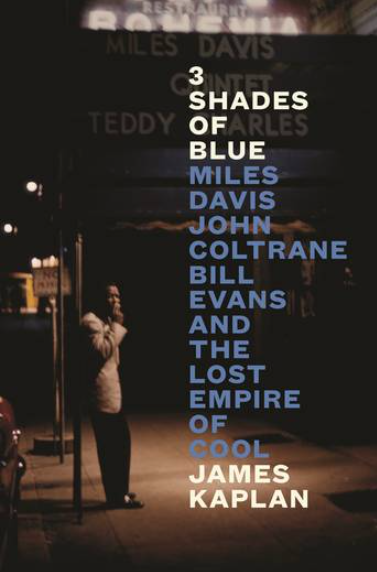

Review: 3 Shades of Blue: Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Bill Evans and the Lost Empire of Cool, James Kaplan, Canongate

It’s hard to imagine now, but in the 1950s in New York you could go to tiny clubs with a handful of other patrons and see the cream of jazz history. It’s after the war and things are changing: these little clubs only fit enough people to either play or listen. Patrons are no longer dancing in big halls, swing has morphed into be-bop, played at a furious pace. Bands are smaller: two musicians stand in for a whole horn section. They trade motifs, reinterpreting the traditions.

On any given night you can hear Charlie ‘Bird’ Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Sarah Vaughan, Thelonious Monk, Art Blakey, Charles Mingus, McCoy Tyner, Ornette Coleman, Cannonball Adderley, Sonny Rollins – the list goes on and dizzyingly on. The up-and-comers include Miles Davis, John Coltrane and Bill Evans.

Miles comes from the mid-west. His parents are well-off but it’s a volatile household – his parents separate. He has played in bands in St Louis, sitting in for a regular off sick. He moves to New York at 18; his father sends him to Juilliard. Miles becomes tired of the racism there, but he is knowledgeable and is appalled at the musical illiteracy of his peers and idols. He makes his mark jamming with Parker and Gillespie. He is arrogant and cultivated.

By the mid-50s Miles has found the sound he wants; he uses a mute, and his trumpet sound becomes intimate yet distant (and yearning). The sound becomes ‘cool’, after the heat of be-bop, as in The Birth of the Cool, his famous album.

John Coltrane lives in North Carolina until a move to Philadelphia, a hotbed of jazz, where Hank Mobley, McCoy Tyner, Jimmy Smith and Philly Joe Jones play. Coltrane, like so many others, is in awe of Parker since he saw him in Philadelphia as a teen. The same age as Miles, Coltrane is nevertheless not as flashy and confident, but he is quietly committed. It seems like his saxophone only leaves his lips when he eats or sleeps. In a young band with Red Garland, he switches from alto to tenor sax from necessity, and gradually he sounds more like himself, less like Parker.

Parker is a genius, but a heavy heroin user, to say the least. Heroin is ripping through the jazz scene, tragedy amongst the novelty. Parker uses it as an antidote for American society, but others use it because it is an essential part of the scene, marking those who are ‘in’. It is a way to feel hip and included, for Black men who are seen as second-class (or non-) citizens. After returning from Paris where he wasn’t treated as inferior, Miles is depressed and starts his own heroin habit. Articles in jazz magazines discuss the toll heroin is taking.

Bill Evans sees heroin as a badge of being ‘in’, but he is white. Some wonder why Miles has this nerdy white guy in the band, but Miles is, he says, just interested in talent, irrespective of race. He hears something in Evans, despite Evans’ hesitancy about his own talent, which only makes him practise more. Like Miles, Evans knows his classical music, and they can discuss it for hours.

Evans and his wife, appallingly, seem to love the junkie life, but it takes its toll, inevitably. Evans has so much nerve damage from his addiction that he has to play one-handed at one point. (In the early 60s he is recording largely to pay off drug debts.) By the end of ’58, before the making of Kind of Blue, Evans is burned out and he won’t play live again with Miles.

In ’54 Miles kicks heroin, annoyed, amongst other things, because people are saying he’s washed up. In ’57 he kicks Coltrane out of the band, as his addiction is making him unreliable, just as Miles had been. Coltrane goes on to play with Monk, and they make a sensation. Then Coltrane makes Blue Train, another stellar, legendary release.

Then for a sparkling moment Davis, Coltrane and Evans come together to make Kind of Blue, both the best-selling and the most lauded jazz album ever. Miles wants something like the spontaneity of Japanese master calligraphy. He is also inspired by gospel and African ballet. He has decided music at that point has become ‘too thick’, with its jammed-together chords. He aims for the freshness of first takes. Little is mapped-out, and they play in a near-to live setting in an old church.

‘So What’ builds to Miles’ first solo from tentative bass and piano, over shimmering ride cymbal. The solo has echoes of what has come before but the song has a minimalist two-note riff, now on trumpet, now on piano, so pleasingly cool and calm, like lapping waves. The other songs, also originals, follow suit. On its release, reception is muted. Some sense its greatness, but many are not entirely sure of what they are hearing. Gradually its genius creeps under the skin of pop music culture.

Then they go their separate ways. Quietly spiritual, Coltrane goes on to make A Love Supreme. He is now at the height of his powers, while jazz is heading down weirder avenues, all exploration and discovery, not to the taste of everyone. By the start of the ‘70s Coltrane is playing free jazz and Miles makes Bitches Brew, the second-highest-selling jazz album of all time. But the album blurs the line between jazz and rock – is it a new horizon or a dead-end?

Also, Miles is into cocaine, as is Evans, who, crazily, is nostalgic for his heroin addiction, after his wife dies, and relapses. It’s another dead-end. Coltrane dies young, like so many others, in 1967, officially from liver cancer, but his addictions have taken their toll. Evans is gone by 1980.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.

1 thought on “The Empire of Cool”

I wonder what Bill would think about all the attention he has been given in the afterlife?