Review: Otherlands: A World in the Making by Thomas Halliday

The Silurian: in the seas, nautilus and trilobites are still hanging around. The first bony fish are swimming, avoiding large sea scorpions. Gondwana dominates the surface of the Earth, the plates have congealed into a big land mass at the South Pole. Nearer the equator, North America is a scattering of islands, barely a constellation.

The atmosphere has only half the oxygen concentration it does later, but the first plants are on the move. Cooksonia, a tiny, branching, vascular plant without leaves, proliferates near waterways. Away from streams, not much grows, but in wet areas, there is a mini forest, punctuated by giant, 8-metre-high fungi, the biggest organism thus far, like a pointed mushroom stalk without a cap. Tiny millipedes scuttle about. Cyanobacteria thrive in hot pools. Soil is only just in the process of being made; without a covering of soil and large tree roots, water gouges rock. Later, in the Carboniferous, huge strands of trees that die en masse when they simultaneously come into seed come crashing down in a matter of weeks. The rot can’t keep up and the trees turn to peat, then coal. This world dominates for millions of years.

The past is not only a foreign country (as L.P. Hartley wrote); it is also unable to be visited. But fossils tell us more and more amazing things as science progresses – the anatomy of long-extinct creatures, how they ran, what they ate, what colour they were, how they sounded – and not just from bones. Trace fossils – burrows, footprints, fossilised eggs and dung – all have a story to tell. From sand grains in rocks, the landscape can be inferred. From ice cores come information about atmospheres and tree cover. It’s incredible: the tell-tale chemical signatures of the wax of plants can be found in rocks (which hardened from the soil the plants grew in). And more recently, there is more understanding of how organisms interacted. Science sheds light on the ecosystems of the Palaeozoic and Mesozoic.

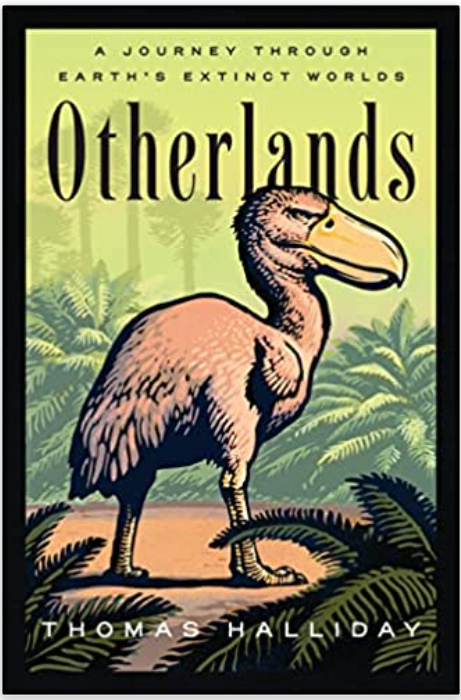

These are the ‘otherlands’ that Thomas Halliday envisages. Take the God’s eye view: If the video of the history of life on Earth were to be run in incredibly fast fast-forward, we would see ecosystems come and go, continents sliding, ice advancing and retreating, migrations of animal species. Imagine the fecundity described in Genesis. Then add another dimension, time. Tyrannosaurus lived about 66 million years ago, Diplodocus 150 million years ago. There is less time between us and T-Rex than between T-Rex and Diplodocus. The world of the dinosaurs is not one but a multitude. And then this, the Mesozoic, is only a slice in the abyss of time. There are worlds upon worlds upon worlds, and Halliday is a nature writer with a time machine.

He begins with the Pleistocene (20,000 years ago), then works his way back, as the landscapes become progressively foreign. He writes about the migrations of camels into Asia from North America. Humans go the other way. He describes how, five million years ago, when the strait of Gibraltar closed, the waters from the Nile and the northern rivers weren’t enough to replenish the Mediterranean, and it became a dry salt pan with hellish temperatures. When the Atlantic finally breaks through, via an enormous waterfall, so much water flows that the whole body of water rises a metre every two hours. On islands in the Mediterranean flightless geese gradually grow gigantic, elephants become tiny. There are tropical penguins.

Halliday can be surprising. You’d think a chapter on Hell Creek in the USA, a famous dinosaur site, would be about T-Rex and Triceratops, but he skips to the end of the story, and the massive asteroid impact, the most recent in a series of mass extinctions, until the man-made asteroid of the Industrial Revolution, only possible because those wily mammals will ride it out, underground possibly, and in the company of canny birds, those survivalist dinosaurs.

Earlier, in the Triassic, just after another mass extinction, the dry-land world is another supercontinent (Pangea). There are thick soils from fallen leaves and rotting trunks. There are no bird calls or flowers. (Yet to be invented.) But cycads, conifers, ginkgoes and ferns are abundant, and on every foothold, there are lichens and mosses. Insects are abundant too. There are grasshoppers with 50cm wingspans. And taking to the wing for the first time are vertebrates. It is a time of experimentation. There is a huge range of forms. The prototypes of dinosaurs are beginning their long reign, which vastly outlasts that of humans. But alongside, mammals are diversifying. They will hold on, threading their way through the abyss of deep time, eventually to us.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.