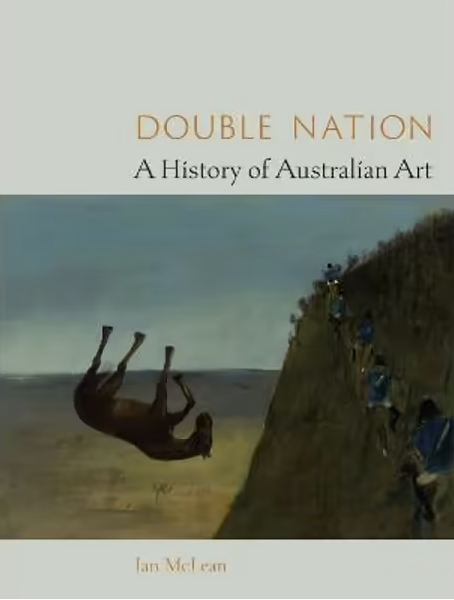

Review: Double Nation: A History of Australian Art, Ian McLean, Reaktion Books

Artists don’t always intend for their art to represent the nation, but national galleries look for works that say something about a collective experience. In Australia this is complicated by the ‘double’ histories of colonial and Indigenous Australia.

Ian McLean begins his (succinct, glossy but affordable) history of Australian art in 1788, following the likes of Robert Hughes’ 1966 history. This might seem narrow, but McLean has recently written a history of Australian Indigenous art (Rattling Spears), and he sees that art as an important stream parallel to art made in the European tradition by those with European backgrounds. He is also aware that the nation was founded on the exclusion of Indigenous people, so it is realistic to recognise that the history of mainstream Australian art has likewise been, unfortunately, exclusionary.

This exclusion meant that Australia suffered for decades under a kind of cultural schizophrenia – celebrating the continent’s distinction while simultaneously continually referring back to the ‘mother country’ – which meant competing perspectives on art even within the European tradition.

Later there were grand, celebratory re-enactment paintings of the colonising moment in 1788, legitimising the act of dispossession. But the first art made in Australia by Europeans tended towards natural history, with depictions of the struggling colony amongst strange flora and fauna. Some of these artworks are exquisite and perceptive, but they also tend to depict Indigenous people as like other antipodean curiosities, at the fringes of (struggling) civilisation.

As the colony outgrew its prison beginnings, it was conceived as a new England. It is often said that early painters couldn’t ‘see’ the landscape properly, but this is possibly not accurate. It is more likely that they wanted to soften the views of Australia to make it more like their bucolic homeland, as well as simply painting in a tradition, which occurs across the history of Australian art. John Glover’s painting of Mills Plains in Tasmania can hardly be said to be unsympathetic. At the same time, pictures of tamed wilderness hid the dark reality of genocide, and paintings of wilderness excluded, with some exceptions, the original inhabitants. Even Streeton and Roberts would contribute to the myth of terra nullius by depicting their visions of a wilderness tamed.

The Heidelberg School is now seen as a watershed in truly representing the country’s land and light, but McLean notes the experimental nature of these paintings, and that they didn’t go over well, initially. McLean suggests that the likes of Streeton and Roberts were searching for rather than finding iconic landscapes. Streeton was simultaneously trying out Symbolism and placing mythological nymphs into his works. Similarly, Hans Heysen is now seen as the iconic painter of eucalypts, for the first time imbuing them with heroic, individual spirits, but, incredibly, not all viewers were impressed at the time.

Part of the ‘double’ nature of Australian art has been the tension between following British style and being independent enough to forge our own style. In the 1920s, Art in Australia magazine said that Australia lends itself to harsher, harder art forms: beginning with Heysen, artists turned to the desert, then to the newly positive interest in Indigenous art. Margaret Preston attempted incorporation rather than appropriation of Indigenous art to find an Australian sensibility. Judging by the number of paintings McLean reproduces here, he sees Preston as key in the attempt to bring Indigenous elements into European-style art, but whether her art was incorporation or appropriation is currently debated.

In the middle of the twentieth century, optimistic, inter-war paintings that focussed on Australian content, such as beach-going, gave way to Nolan, Boyd and Tucker’s modernist, sour, myth-soaked images. We had our share of Surrealists, Expressionists and Cubists, trying out the art of Europe in a different setting. Iconic Australiana still dominated: outback, bushrangers. But Nolan’s Ned Kelly series didn’t make much of an impact at the time. Russell Drysdale gained acclaim for his outback paintings, but probably their most radical aspect was how they returned Indigenous people to the landscape, with unusual dignity. Even so, McLean suggests, it is indicative of how tied Australian art still was to Britain that Nolan, who had moved there permanently and was celebrated for his outback paintings, was included in a book about ‘British’ artists. Nolan, for his part, though, despite his subject matter, saw himself as an ‘international’ artist.

After World War II, as happened in the US, there was division in the art world over abstraction – a divide that now seems, as McLean notes, arbitrary. The art of John Olsen, for example, may seem messily abstract, but like Indigenous art, it often has an aerial perspective and contains plenty of figurative details. Fred Williams, likewise, was a landscape painter who tipped towards the abstract, and seemed to find something quintessentially Australian. McLean relates the story of Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri getting excited over one of Williams’ works. In contrast, colour field painting never quite took off here. It seems to have lacked some Australian essence.

McLean’s story trails off in the 1980s, largely because there began there a shift from the ‘double’ nature of Australian art to multiplicity, and McLean argues that that is another story. We, therefore, miss out on, say, Howard Arkley and Rosalie Gascoigne (who also combined the abstract and landscape to great effect). Others, whose subject matter seems iconic Australiana, such as Brett Whiteley and Ken Done, are not discussed either. His chronological frame makes some sense, I guess, as, ironically, the broadening of influence from Britain to the whole world, and the growing prominence of Indigenous art, undermined the idea of a national style. But, as in other areas, debate about what is distinctively Australian hasn’t exactly gone away.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.