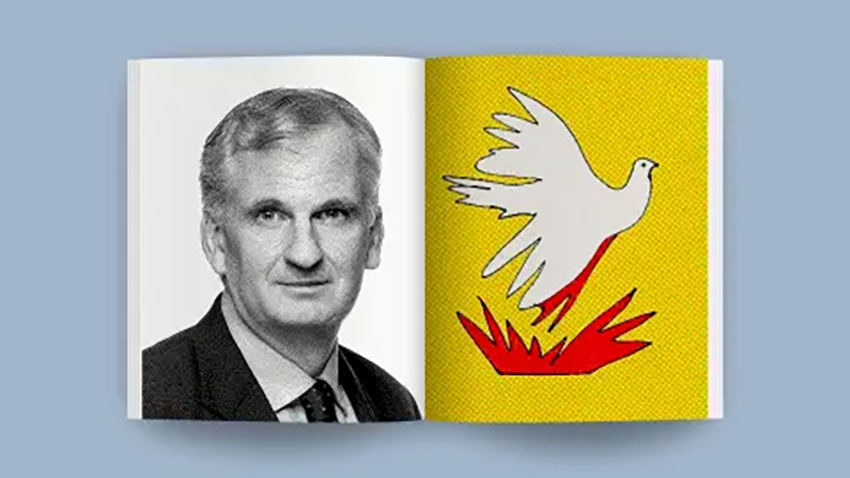

Review: On Freedom, Timothy Snyder, The Bodley Head

After the disastrous US election result, and with constant talk of that very American obsession with freedom, it is good to be reminded of why odiousness (rather than cream) rises to the top and why, against the lies of tech giants and populists, being free is a constant, slow build.

Timothy Snyder is the author of the widely read On Tyranny; now he has written On Freedom. An acquaintance of the Ukrainian president, Snyder also teaches a course on politics and philosophy to American prison inmates, so he knows the depth of importance of freedom. Building on the work of Simone Weil, Vaclav Havel and others, in this new book he investigates how freedom works through the areas of sovereignty, unpredictability, mobility, factuality and solidarity.

Crucially, he argues that we need to think of freedom as ‘freedom to’ rather than ‘freedom from’. ‘Freedom from’ is a focus on means rather than ends. It is tempting to think that the removal of barriers is the essence of freedom, but Snyder argues effectively that without a path mapped out, or at least available, we can’t move successfully anyway.

A negative view of freedom focuses on restrictions, provided, often only perceived, from government or illegal immigrants. Alternatively, a positive view of freedom promotes education, understanding of history, the benefits of equality and working together. Snyder writes that ‘freedom from’ was not enough for Russia after the 1990s, when it was theorised capitalism would transform the former Soviet Union for the better. Instead, it collapsed back into tyranny, with oligarchs quickly monopolising resources and Putin able to consolidate power and spread lies and hate.

Similarly, Americans think capitalism equals freedom, but the free market should be instead named the ‘uncontrolled market’, one which has created inequalities and division, as well as environmental catastrophe. Americans, and much of the world, are enslaved by consumerism, a means that has become an end. (Consumerism is not a tool of just capitalism; Snyder writes that communists in Eastern Europe used it to suppress dissent.)

Inequality restricts freedom. It is clear that in the US the freedom to make money and flourish is restricted to only some, dependent on birth, class, skin colour. In the case of the newly re-elected president, Snyder writes that he doesn’t even have to make things better, he only has to cast blame elsewhere – one of his lies is that inequalities are the fault of the already marginalised, such as immigrants, rather than of rich elites like himself. Demonising others, writes Snyder, might make you feel better about your own imperfect situation, but that is not freedom.

That kind of language divides, driven by the idea that if I win, someone else must lose. This is the logic of capitalism and competition. That can happen if I see others as the enemy, and think the government gets in my way. But the alternative, evident in countries where there is better government spending, is that investing in the public sphere helps all. The argument that government gets in the way is made by billionaires who have benefited from government but now want to avoid taxes and is parroted by those who mistakenly think their problems are caused by too much government, rather than mismanaged government.

At the centre of this is a notion of individualism where people are free from taxes, free from the obligation to help others. But this is not freedom, only a slavery to selfishness, a sad lack of recognition of the fact that I can’t have freedom on my own. Edith Stein argued that freedom only comes when we as individuals are not the centre of our vision.

The language of tyrants, from Thatcher to Trump to Putin, perpetuates inequalities by claiming that there is no other way. This is wrapped up with a deliberate blindness to history. We can see this in talk of Trump being the best president ever, or that America was once great (for whom?), or that Ukraine was always part of Russia. A blindness to history means that those in power can rewrite it, as fictionalised by George Orwell in Nineteen Eighty-Four. Freedom involves not being beholden to the past but in remembering it and learning from it.

Social media is allowing the dissemination of this distortion of facts. In contrast, seeking truth is freedom, according to the likes of Simone Weil. Americans, Russians, Chinese (and Australians) are entangled in lies. And whether we are reading lies or truth online, our digital structures entangle us, making us, via algorithms, predictable – a form of control, one being successfully implemented by the Chinese government.

Both Weil and Vaclav Havel, the Czech dissident and subsequent president, spoke about the value of unpredictability, and how that illustrates the complexity of society. Here they are not talking about impulsiveness, but about understanding the richness and value of human lives, when we recognise what lies behind human unpredictability. Humans reduced to the predictability of machines are restricted, reducing our ability to solve problems, reducing us to accepting the lies from tyrants that there is no other way.

In a church setting it is good to be reminded that there is an alternative, but one that can’t be enforced by tyrants (as the conservative American church seems to think). The Lutheran theologian Robert Jenson wrote (with the danger, perhaps, of oversimplification) that the message of the Bible is that the God who freed the Israelites raised Jesus from the dead. In this assessment, faith is freedom. But Snyder reminds us that there is a danger in focussing on eternity and turning aside from the moment now when action is needed.

Snyder might also help us remember that salvation is communal, not individual, that escapism is not helpful, that doing good is a matter of the interpersonal rather than just rhetoric and doctrine, that our purpose is to help people flourish and be fully human, rather than restrict them so they seem like everyone else, and that this happens in small settings rather than on the grand political stages.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.