Review: God: An Anatomy, Francesca Stavrakopoulou, Picador

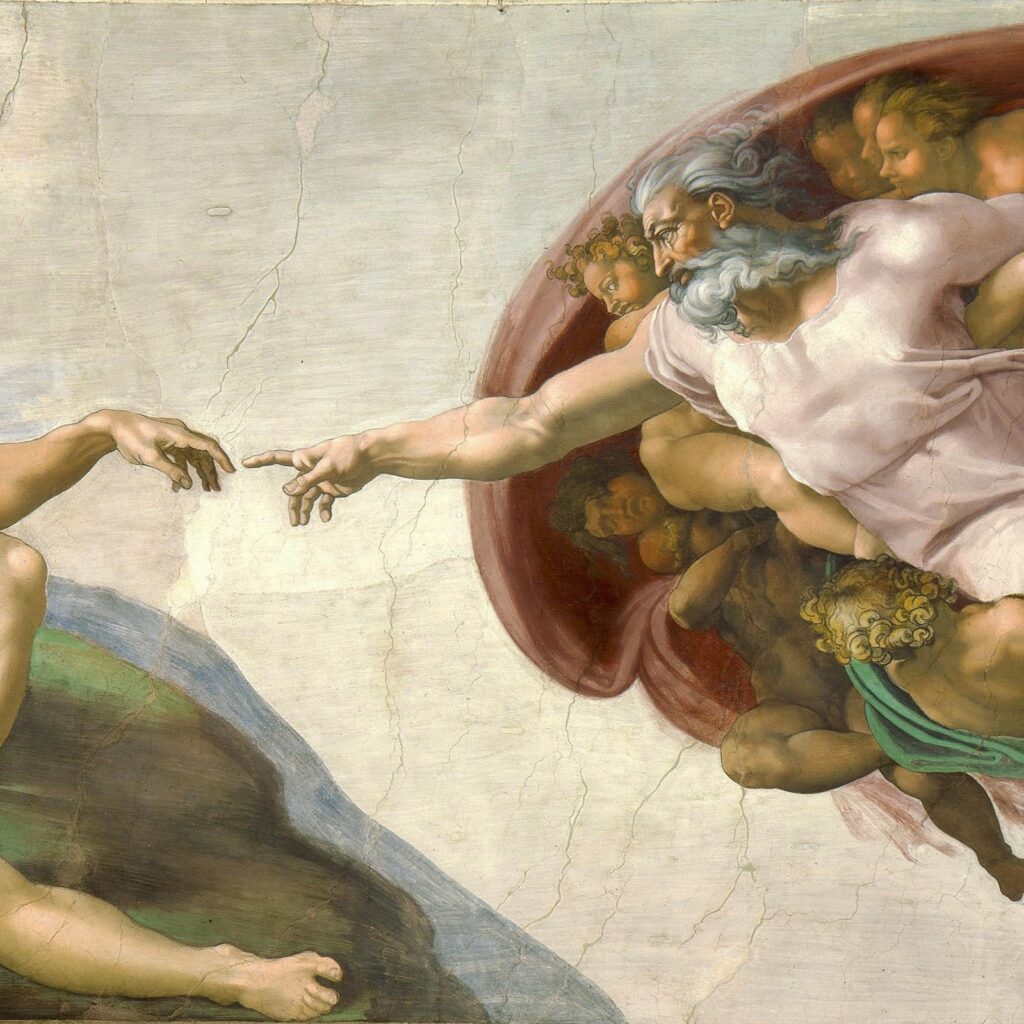

Modern churchgoers think of the picture of God as an old man with a beard sitting on a cloud (as in Michelangelo’s famous depiction) as purely metaphoric (I assume), and in theology, God is spoken of in abstract terms – as essence, prime mover (the cause of all things), his love being indivisible from his being, not being a ‘thing’, and so forth. These ideas are partly the legacy of Greek philosophical thought.

Though they obviously couldn’t see Yahweh, the Israelites understood God in less philosophical and more physical terms. In the Bible we see traces of early conceptions of the god El as one of a pantheon of gods and rather anthropomorphic, more like other Near Eastern gods. Francesca Stavrakopoulou says a more ethereal God is ‘at odds’ with the early Jewish Bible’s image of God. This God was not ‘bodyless’ but ‘hidden’, a god whose robes filled the Holy of Holies, who presented his back to Moses, whose ears were not always open to the pleas of the people.

In this extraordinarily detailed and provocative book, she concentrates on the physical attributes of the Jewish God. She begins with his feet. God walked in the garden, a sign of ownership of the land in ancient cultures. He used the Ark of the Covenant as a footstool. The Church Fathers said all this was symbolic – and that is the way we would read it now – but this was not necessarily the case for the original Israelites. In thinking symbolically and ethereally we lose some of the physicality, emotion and descriptive power of Scripture. God’s relationship to his people is described in frank sexual (or marital) terms, and descriptions of God crushing his enemies are bloodcurdlingly vivid.

The Greek gods were lusty, hungry, thirsty, sleepy, fickle, and we see similar attributes in the Old Testament God. How much is literal and how much symbolic is conjecture maybe. Did the Israelites really think God was going deaf? Or were they just perplexed at the seeming silence? But Stavrakopoulou makes the point that ancient peoples thought of the world in more porous and less demarcated terms than we do.

Sacrifices in the temple weren’t merely symbolic. The people seemed to think the aromas of incense or roasted meat were actually pleasing to God and provided some sort of sustenance. Except that the prophets relayed God’s displeasure at times when the priests prioritised such ritual gestures over justice and mercy. (This is a perennially cautionary tale for people of faith.)

The book utilises a myriad of archaeological finds and is jam-packed with detail: God got his hands dirty when he buried Moses – Moses’ importance signified by the fact that God defiled himself by touching a corpse. Later Jewish scholars thought God, in some way, kept his own Sabbath rituals, including wearing the phylactery. Faces in ancient cultures were central – it was important that Moses could talk to God face-to-face. Which makes it odd then that at Sinai God wouldn’t let Moses see his face. The people ‘longed’ to see God’s face – this meant connection and the bestowing of favour. Most temples had idols one could gaze on, and be gazed upon, something prohibited in Judaism. Despite this prohibition, coins for tithes were minted with Yahweh’s ear on them, in the hope that Yahweh’s ears would hear the petition. God is described as having a fine, long nose – the nose being not only a key component of physical beauty, but also a site of expression of anger (snorting, flaring). Rather than a wise old man, Yahweh is pictured as a buff warrior.

Some of this may be surprising to those readers whose image of God is a filtered, modern one (the straw-god of the atheists, Stavrakopoulou notes). But the modern image of God minimises the obvious fact that the Bible is a record of a developing understanding. In later Judaism and in the church, of course, the idea creeps in that God cannot be held to our mere descriptions and representations, and that these limit our theological understanding – that they are merely us creating God in our image.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.