On 22 October, some 100 people gathered in Wesley Mission’s conference centre to hear from First Nations theologians.

Walking Together, the inaugural First Nations Theology Conference, featured four keynote speakers. At points challenging, this was a look into the theology of stolen land and what it meant for the Uniting Church to acknowledge the dispossession and role of Indigenous Australians.

The day began with a Welcome to Country from Aunty Yvonne Weldon from the Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council, Yvonne Weldon is an independent councillor for the City of Sydney and the first Aboriginal councillor in the City’s 180-year history. Yvonne is a proud Wiradjuri woman. She was born and raised in the inner city of Sydney but maintains strong ties to her homelands of Cowra and the Riverina areas of New South Wales.

The first keynote speaker for the day, Dr Anne Pattel-Gray, spoke on the topic, “Raising our Tribal Voice.”

Dr Pattel-Gray is Professor of Indigenous Studies and inaugural Head of the School of Indigenous Studies at The University of Divinity. Dr Anne Pattel-Gray is a descendant of the Bidjara / Kari Kari people of Queensland and a celebrated Aboriginal leader.

“The vision of walking together has been a lifelong goal for [indigenous people]

“In the 1980s and 1990s the [Congress] forged a relationship with the Uniting Church…To lead the way in calling for accountability of its churches and the entire nation.”

Dr Pattel-Gray said that Rev. Charles Harris’ vision was more relevant today than it was, as this was founded on the desire for First Nations people to be self-governing.

This, she said, included “de-colonising” readings of scripture.

She said that first nations people’s experience must form part of the task of theology, such as the stolen generations, the destruction of Indigenous people’s lands, and ongoing removal of children. and high incarceration rates.

“The colonial view of God is one that separates the creator spirit from the land. It is not one that Aboriginal people can relate to,” Dr Pattel-Gray said.

The topic of a potential Indigenous voice to parliament was a repeated topic for the the conference. Rev. Pattel-Gray said First Nations Peoples required a voice to parliament, so as to “secure the same rights, wealth, power, and privilege, that is enjoyed by all other peoples.”

“Aboriginal people have got to be recognised by the constitution,” she said.

“We’re tired of other people talking for us. That’s why we’re going to need to have a voice to parliament.”

“Those steps, and educating people, and bringing people with us, are going to bring us to…a treaty.”

“I think the wonderful thing that churches could be doing in driving the truth commissions is leading by example…and start setting the record straight.”

“In this journey, is our redemption as a nation.”

Preparing to walk together in ancient lands

The second keynote speaker was Naomi Wolfe, a trawloolway woman. Ms Wolfe is a Lecturer of Indigenous Studies at NAIITS: An Indigenous Learning Community, Australian Catholic University.

She spoke on the theme, ‘Preparing to walk together in ancient lands.’

Ms Wolfe said there was no relationship yet based on honesty and justice.

“When our kids can’t walk the streets… without being attacked by vigilante gangs…there’s an urgency here,” she said.

“When Aboriginal churches and congregations are closed because of efficiency, and megachurches remain, there’s an urgency.”

“Can we have healing if we don’t acknowledge the pain and causes?”

She said that there was a “sickness” in Australian society as a result of unacknowledged pain.

This sickness came despite the nation having moments of hope for reconciliation, including the year 2000 march for reconciliation and later, the 2008 Parliamentary apology to the stolen generations.

After the latter, she recalled, ‘never again’ was a popular sentiment. However, children have since been removed from their families in record numbers.

Ms Wolfe said that some hope remained and that Indigenous people had resilience and senses of humour that carried them through.

She added that she did not believe reconciliation was a matter of individual guilt.

“I believe in a faith that is renewing, and is redemptive, so all is not lost,” Ms Wolfe said.

According to Ms Wolfe, telling and exploring were necessary for indigenous and non-Indigenous people to walk together.

This included churches finding out on whose land they were built.

“It means holding our church communities responsible and asking those hard questions,” she said.

“So often the burden is on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to facilitate these processes.”

Ms Wolfe suggested it was now time for non-indigenous Australians to shoulder the burden.

“It’s time for your communities to do the work,” she said. “What might it look like if your agency started the process for decolonisation?”

“As a historian, I want the richness of Indigenous history to be shared and acknowledged.”

“There’s a sense of urgency to all of this.”

A Kairos threshold of opportunity

Rev Dr Garry Deverell is an Anglican priest and lecturer and research fellow in the School of Indigenous Studies at the Melbourne-based University of Divinity. Rev. Deverell is a trawloolway man from northern lutruwita/Tasmania who currently lives in Naarm/Melbourne.

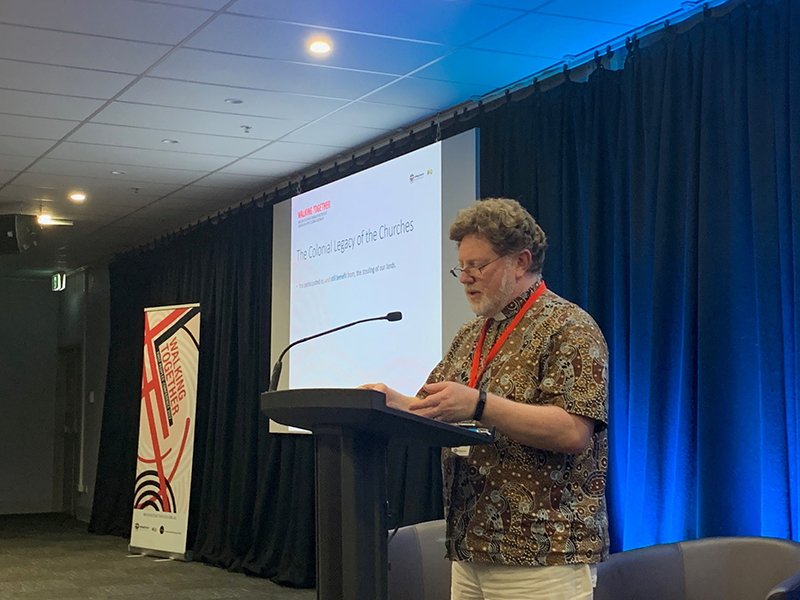

He presented a wide-ranging address, this time on the theme of how the church might redress inequity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

Rev. Dr Deverell pointed out that those who participated in the massacre, frontier conflicts, and genocidal government policies, were overwhelmingly Christian.

“Many of you continue to deploy an imaginative terra nulius regarding our people by pretending that we don’t exist.”

“How are the churches, cooperatively, to reckon with the legacy of colonialism?”

Rev. Dr Deverell quoted from Philippians 2.

According to Rev. Dr Deverell, there was a direct point of comparison between the Philippians passage and the contemporary church, as contemporary non-indigenous Christians benefited from the stealing of others’ land, and that this mirrored the Philippians’ context.

“How do migrant Christians in churches that are still dominated by euro-centric theologies, those who have empowered themselves at the expense of Indigenous people, let go of that power and reclaim it in a more…health making kind of way?” he asked.

“If you are Christians, it cannot be a matter of whether you return this power, but how,” he said.

Paul, in the context of Corinthians 8, commands Christians in a wealthier church share their resources with a poorer church to redress the imbalance between them.

He indicated that the process might involve treaties on the local level.

“A treaty is a relationship.”

Rev. Dr Deverell presented a challenge to churches to hand land back to traditional owners.

“One way churches came to receive land was the crown took it from us and passed it along to them without fee or compensation.”

At the denominational level, this included making arrangements to hand properties churches were originally given by the crown back.

At the congregational level, he challenged churches to contribute 10 percent of their annual budget to ministries run by Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people.

He said it was a part of the concept of “Setting up camp in the Centre.”

“The fruit of these ministries would make for stronger mob,” he said. “The churches should allow us to set up camp in the centre of your corporate life. The place where decisions are made about ministry and mission.”

This, he said, would also help the church.

“Your churches are in decline because they are seen as being irrelevant and too corrupt,” he said. “The churches need to get with the program. They need to get with what the spirit is doing in the world. You need us and our theological perspectives.”

“Our theology is really different to yours,” he said.

Rev. Dr Deverell said the church was at a “Kairos threshold of opportunity.”

A new beginning for Congress

Rev. Mark Kickett is the Interim National Chairperson, Uniting Aboriginal and Islander Christian Congress (UAICC). A Noongar man from south west WA, Mark was ordained a minister in the Baptist Church in the 1990s. His ministry has taken him from Brisbane to Perth, Broken Hill and Kalparrin near Murray Bridge in South Australia.

He presented a keynote session devoted to the history of the Congress and what needed to happen in order to better promote its vision.

“The place that the First Nations People have in our church is paramount,” he said.

Rev. Kickett said that colonialism was, in the words of J. Kehaulani Kauanui from Wesleyan University, “A structure, not an event”

Against this, Indigenous peoples exist, resist, and persist, and second, that settler colonialism is a structure that endures indigeneity, as it holds out against it.”

“It’s really clear that we build who we are on two world wars, especially the first world war.”

“Out of that we have built this larrikin image that defines what it is to be Australian”

Rev. Charles Harris, he recalled, returned from a Christian Conference of Asia gathering in the Bay of Plenty, New Zealand in early 1982 with the question “Why couldn’t Aboriginal Christians, like Māori Christians, take control of their own destiny?”

22-26 August 1983 was where the Congress was inaugurated. While it was a big event, according to Rev. Kickett, knowledge of the Congress was not widespread.

“There is a blockage somewhere that does not allow the seeds of this relationship to trickle down to the people in the pews,” he said.

Rev. Kickett shared meeting several people who had never heard about the Congress and the Covenant.

He said that Congress now faced a question of, “how serious the relationship between the Congress and the uniting church is.”

“There is hope and expectation in this gathering.”

The event had the subtitle, How can the church embrace indigenous peoples theology in a post-colonial Australia?

Nathan Tyson was the event MC. Mr Tyson works with the Uniting Church Synod of NSW and ACT in the role of Director, First Peoples Strategy and Engagement. Nathan is an Aboriginal man who has spent most of his life in Sydney and is of Anaiwon/Gomeroi descent (with connections to the Brown, Munro and Sullivan families from the Tingha region in North Western NSW).

He acknowledged that the subtitle implied that Australia, “was not there yet” in terms of being a nation that was “post colonialism.”

Moderator Simon Hansford opened the event. He said there was much to the use of “embrace” in the event title.

“It isn’t tolerate, it isn’t endure, it…requires work and time,” Rev. Hansford said.

“There is hope and expectation in this gathering.”

Rev. Hansford said he looked forward to, “many more years of this gathering.”

As well as the keynote addresses, there was a performance from the Pymble Ladies College First Nations Students.

Photos from the morning and afternoon sessions can be found on the Uniting Church Synod of NSW and ACT’s Facebook page.

Visit the Uniting Church Synod of NSW and ACT’s First Nations Resource page for information and other helpful resources.

4 thoughts on “Inaugural conference asks how we can Walk Together with First Peoples”

Jonathan, perhaps you can edit this to indicate the Nations to which the speakers belong. I imagine this was part of their introduction and as important a part of their identity for them as their academic qualifications and positions.

Thank you for pointing this out Judy, the article has been updated accordingly.

Thanks. I notice several of the names begin with lower case letters. Is this a convention that I’m not aware of, or the result of hasty editing? 🙂

Embracing indigenous theology is central to the renewal of Christianity as an authentic ethical voice and vision. I was so pleased to hear the discussion at the Indigenous Theology Seminar of the role of Reverend Charles Harris with the Uniting Aboriginal and Islander Christian Congress. Here is a book review I wrote of A Struggle for Justice, the biography of Charles Harris, by Uniting Church theologian Rev Dr William Emilsen.

Robbie Tulip

A Struggle for Justice tells a gripping story about a man who should be celebrated as central to recent Australian history. Charles Harris is a giant in Australian indigenous religion, as Founding President of the Uniting Aboriginal and Islander Christian Congress and main organizer of the Aboriginal March for Justice, Freedom and Hope on 26 January 1988.

Dr William Emilsen has written a superb biography of Harris, scholarly, thorough, highly readable and engaging, and above all important for its contribution to public knowledge of a great Australian. The background to this story is the traumatic pathology of the physical and cultural genocide of Aboriginal Australia, in the direct harm to Aboriginal people and in the culture of silence resulting from white Australia’s denial. The emerging message is the potential of Christian faith to provide a universal reconciling story for all.

There are several themes of great interest in Emilsen’s excellent account. The role of the Uniting Church in supporting indigenous spirituality is a constant, as are the various political tensions generated by Aboriginal religious activism. The personal story of Charles Harris has much broader relevance than within religious history alone, with his unwavering Christian faith, his strong Biblical foundations, the political importance of his achievements, and also the growing radical anger that built up in his heart over the course of his life, grounded in the gospel values of the life and witness of Jesus Christ.

The record of events in this biography is of immense value, especially with the establishment of the Congress and organization of the 1988 March, which became both a way of mourning the impact of loss and a celebration of an emerging vision of support for Aboriginal identity. Charles’ speech to the rally in Hyde Park emphasized Aboriginal spirituality as a foundation to work together.

The role of theology in generating political change is highly contested. Christian missions in the colonial period had a deeply ambiguous role, in some ways helping to protect Aboriginal people but in other ways participating in the broader process of cultural destruction. Charles Harris began within a Pentecostal environment, seeing faith in dogmatic literal spiritual terms, but his attitude steadily shifted to a focus on doing the will of God on earth. Toward the end of his life, cut short by heart disease, he told the Uniting Church that his harsh words came from the depth of love, commenting that “the vocation of Christians is to change the world, not to draw people out of the world” (p207).

Such views about social justice were not accepted by all Aboriginal Christians, in view of the role of a conservative faith in providing personal protection against moral collapse from alcohol and violence, and in light of the ongoing influence of colonial theology that completely rejected traditional Aboriginal culture. Harris sought to unite both worlds, bringing together the political and religious dimensions of Aboriginal society, but the difficulties he encountered illustrate that social change is a slow process.

Developing a truly indigenous Christianity that can lead the process of cultural reconciliation in Australia requires a theology that is equally true to modern knowledge, to the heritage of Christianity and to the experience and identity of indigenous people. Reflection on such themes seems to have influenced Charles in his insistence that both truth and justice are central moral values. The steps that Charles Harris took upon this journey of healing are valiant and prophetic, and this biography shows how people today and in the future can build upon his great work of faith.