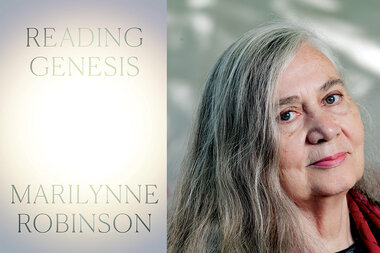

Review: Reading Genesis, Marilynne Robinson, Virago

Genesis is the beginning, but as Roberto Calasso pointed out in his recent study of the Bible, the Genesis narrative rapidly turns from the story of where the universe came from to where the ancestors of Israel came from. Marilynne Robinson agrees it is more family history than cosmological.

While she acknowledges modern scholarship, Robinson sees more theological and narrative cohesion than some scholars, who, she says, aim too low. Despite multiple authors and editors, and a resulting patchwork of text, they knew what they were doing, fashioning a text that insisted on God’s goodness and faithfulness and is remarkably honest about Israel’s faults.

Readers ‘see what they want to see’, she writes, but there is a ‘serenity’ about the Hebrew creation story that sits against the chaos of the doings of imagined gods in the epic tales of Gilgamesh and the Greeks. Bad things happen in the world, but Genesis sees these as against the created order of things. Take, for example, slavery in Egypt, which, she writes, is just taken for granted and is not explained away as punishment for sin. The text is less theodicy – evil is just assumed to be an anomaly – than theophany, the tale of how God promises a land and a nation to a childless nomad who trusts in God but doesn’t seem to understand him very well.

In contrast to the Epic of Gilgamesh, God doesn’t need to eat, sleep or have ziggurats built in his honour. He is not much interested in a proliferation of shrines (humans want to pin him down anyway), the temple is more concession than necessity. Robinson suggests that the story of Isaac’s near sacrifice is an argument (perhaps a rather roundabout one) against human sacrifice. (This may be, but the story remains perplexing and doesn’t exactly show God in a good light.) The Flood story is the best example of how the biblical authors take an older story and twist it, first, to promote monotheism, and second, to insist that God is in control.

Once we get to Abraham, we get to the nitty gritty. What parts of his biography are historical is beyond the point. Here is God, for whatever reason, working his purposes through a family group who, in Robinson’s words, are not paragons of virtue. It is remarkable that the ‘heroes’ are so unremarkable. The fact that divine purpose is enacted through and despite the capabilities and culpabilities of human beings stands against other mythologies that envisage gods as inconsistent as humans, and this difference, Robinson insists, is not minor. (This tension between divine constancy and human fickleness cleverly drives the narrative, and it is unsurprising that Robinson the novelist prioritises this.) An intriguing part of this story is that God uses outsiders and the non-preferred – especially when it comes to primogeniture. Jacob, Joseph and eventually David – they are not the elder, favoured sons. And despite the patriarchy, mothers are prominent.

Robinson is full of awe at the unique moment when Abraham, outside the tent, gazes at the stars and the Lord tells him his descendants will be like them in number, and a blessing to boot. There is, of course, discussion about why an omnipresent God would turn his attention to this small band, but Robinson points out that God, in the Old Testament, is always reminding Israel that they are a vehicle for his wider ambitions. The Jews are the descendants of Abraham, but an integral part of the religion is that there is room for others (a notion that extends later to Christianity).

Robinson makes another interesting point: the text deals with communities, not just individuals. Whole communities are rescued or destroyed despite the merits or not of individuals – something that may be hard for us moderns to understand, unless perhaps we see it as a warning that we can’t live isolated (as current events prove): we’re in it together. And yet, says Robinson, time and again God doesn’t punish where he should; he shows restraint – this against the caricature of an Old Testament God swift to anger.

Genesis is the later Israelite nation looking back, trying to understand their place in the divine plan for the world. As much as the story deals with individuals, Genesis is a tale of humanity as a collective, of our combined hubris, misunderstanding and contradictions, and how a righteous yet sympathetic God deals with that. Here, an understanding of the biblical milieu is important for understanding the text.

Robinson’s reading is an implicit (and occasionally explicit) argument for holistic reading. There is a tendency within churches to contemplate texts in isolation, and within critical circles a tendency to take a similar approach to ‘proving’ the cruelty or inconsistency or sheer unbelievability of God. It is true that the Old Testament God can be puzzling, and, okay, Robinson is quick to see uniformity or benign purpose behind the narrative, but she argues that Genesis has a very carefully worked-out narrative that enhances its power and meaning.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.