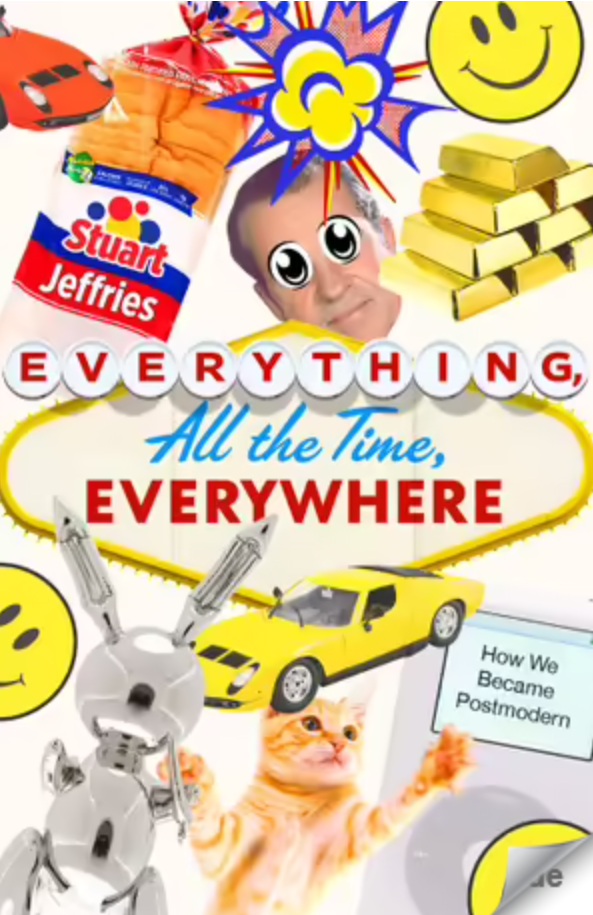

Review: Everything, All the Time, Everywhere by Stuart Jeffries

We are up to our necks in postmodernism, swimming in pluralism, saturated by pop culture, old hierarchies drowned in seemingly endless choice from horizon to horizon. This seems to be simply the way society is now. But, asks Stuart Jeffries, if you dig deeper, is this liberating or another avenue for commercialisation and self-centredness?

Postmodernism is infamous for being wilfully opaque while at the same time celebrating surfaces – of pop music and comics, advertising and pastiche. But Jeffries is able to explain the philosophy while jumping from pop reference to pop reference. He covers the quasi-religious rise of Apple, the morally vacuous Quentin Tarantino and Grand Theft Auto, the identity-shifting art of Cindy Sherman and David Bowie, the overinflated (in size and price) kitsch art of Jeff Koons, the gluttony of streaming TV. And Jeffries can mine below the surfaces, exposing the often-dire political and social consequences of postmodernism. Not everyone would see the connections between Margaret Thatcher and the Sex Pistols (a cynically manufactured pop group if ever there was one).

A key aspect of postmodernism is its rejection of unified thought in favour of a melting pot of ideas. This, somewhat self-referentially, means that postmodernism itself resists one definition, and so, also, it is hard to make sweeping judgements about it. Unless you think that unvarying uniformity is great and anything less, diabolical.

Postmodernism’s emphasis on the cacophonous, fluid and diversified means that amoral relativism is often ascribed to it, but this is misleading. No-one, says Jeffries, believes that the theories of Gandhi and Hitler are equally valid. But postmodernists do question the notion of objectivity and look at bias, including what we might think ‘normal’ society looks like.

More banally (and more fun), global culture is, well, more global. The collapse of ideas of high and low art, beginning possibly with the advent of pop art, means there has been an overdue recognition of the value of folk art (often made by women and minorities). The cosmopolitan ‘jumble’ of cities has made them more liveable, though this has also come with architects forcing kindergarten architecture on us.

More insidiously, there has been a confusion of art and advertising, and globalism has allowed the dominance of mega-corporations such as McDonalds, Apple and Google. And a pluralism of ideas and a focus on pop culture means that it is much harder to see the value of the social, and organise politically, not to mention suggest that any religion can claim to have a hold on truth. Postmodernism undoubtedly hastened a more tolerant – even celebratory – attitude to minorities, to those who didn’t fit in. This is part of its democratising tendencies. But because of the pervasive nature of commercialisation, transgressive identities are quickly harnessed to the neoliberal, all-conquering task of selling stuff. Questioning inequalities turns to online shopping. And the happy pluralism of postmodernism sits oddly with the shrill, simplistic binaries of current political debates, but perhaps underlying this is a fight between those who accept postmodernism and those who fiercely oppose it.

The rise of the internet is an interesting phenomenon that has exposed similar problems. Initially billed as full of utopian potential, there is now ever-increasing concern that the internet is being taken over by, on one hand, ever-more centralised commercial corporations, and, on the other, conspiracy theorists and spreaders of hate-speech, including the governments of whole countries such as Russia and China, who have been able to censor and bend online information for their own benefit.

Being part of a larger, online crowd, Jeffries notes, was meant to expose us to wider views and art and connect us with likeminded individuals from whom we could learn. Yet, a bigger crowd seems able to be steered easier, and desire for the new is channelled into desire for the new and shiny, or at the very least desire for endless, numbing novelty, thereby also enriching those who offer the means for us to connect to the internet. Lost in an online world, we lose touch with reality. Stuck in a fantasy realm, we treat people like commodities.

Supposedly, postmodernism is meant to hasten a decline in authoritarianism, but one effect of a destabilisation of meaning, a ‘semiotic black hole’, as Jeffries puts it, is that there is a loss of community and a lack of responsible government. Politics is focussed on spin, more than ever, and the chaos allows dictatorial leaders to rise while exploiting the proliferation of ‘alternate facts’. The assault of imagery from around the world means that celebrity titillation is mixed in with images of injustice and misery, making it hard to focus on anything. And care is replaced by irony.

What’s in place – or what can we put in place – of all this? Rather than return to mean, authoritarian uniformity, we can keep postmodernism in place and embrace its tendency to open the surprising diversity of the world to us, but simultaneously resist the way this can easily sour into the faux diversity and destructive tendency of endless shopping.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.