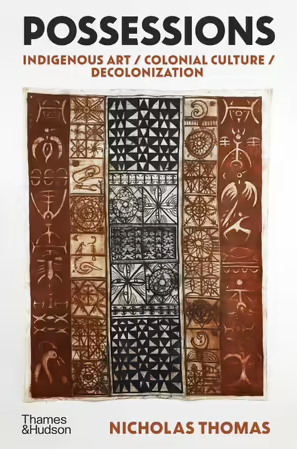

Reviews: Possessions, Nicholas Thomas, Thames & Hudson

European Vision and the South Pacific, Bernard Smith, Miegunyah Press

These two books, published about 20 and 50 years ago respectively, now helpfully reissued with new introductions, address the issue of art and colonisation, which, in the years since they were originally published, has only become more prominent and complicated, with debates over the removal of statues, art appropriation from Indigenous artists, historical assimilation, the return of stolen artefacts, contentious gallery labelling and school curricula.

Bernard Smith was a pioneering art historian who explored a chapter of the history of art and science, namely how explorers (including the artists who travelled with the likes of Cook) pictured the people and art of the Pacific. He recognised that art both reflects and directs culture, and he traced a shift from the Romantic sensibility to the more scientific outlook of later explorers and colonisers. Another way to put this, as Smith did, is to say that as European explorers repeatedly contacted Pacific people, there was tension between the ideas of biblical Fall and Darwinist ascent.

Classical painters were taught to see uniformities in the world, in a kind of idealisation of landscape, so Europeans first encountering the Pacific pictured that world as similar to Europe. Pacific peoples were pictured as noble savages, in line with the Romanticism of Rousseau, a vision of what Europe (supposedly) used to be.

But later European intellectual developments brought a shift, as a more forensic mindset gained ground. So, within Cook’s various voyages we see artists making a greater effort to capture the individuality of flora and fauna and geography. One of the oft-noted strengths of Smith’s book is that he analysed utilitarian art – sketches and watercolours done on the spot – to understand attitudes to the new landscapes and cultures Europeans were encountering.

By the nineteenth century a widely applied Darwinism meant that Europeans, in studying the Pacific, came to believe that Indigenous peoples were on a lower evolutionary rung. This in turn boosted the colonialist idea that Indigenous people weren’t cultivated enough to retain possession of their lands.

The broad-brush summary above leaves out one important aspect of Smith’s book – that within this history there are always contradictions and diversions. Not everyone thought the same way. Some of the interest in the Pacific was sympathetic, some of it combative. This is also an important aspect of Nicholas Thomas’s book, as he too shows that the history of Western and Indigenous modern art in the colonies of Australia and New Zealand is complicated, and, especially, that transactions between colonists and the colonised weren’t one-way. He says his book is about ‘cross-cultural traffic’, both constructive and destructive.

As with Smith’s book, there is a broad argument here that initially, art from explorers and colonists featured Indigenous people. Later, in the likes of the Heidelberg School we see romanticised landscapes. The bush is finally celebrated, but it is devoid of Indigenous people, as if, Thomas says, the colonists were the natives, carving lives out of virgin bush.

In the twentieth century there was a recognition of Indigenous art, and with good intentions, the likes of Margaret Preston in Australia and Gordon Walters in New Zealand used Indigenous motifs, later coming under some criticism for appropriation. Gradually, Indigenous artists themselves were lauded, though there remains the issue of celebrating what non-Indigenous people think of as ‘authentic’ Indigenous art versus a wariness over hybridised and overtly political modern Indigenous art.

Amongst this narrative Thomas recognises that neat lines are sometimes hard to draw. He writes that celebration and appropriation can, of course, go together. And a celebration of Indigenous art can also pigeon-hole it in the past or the fringes of culture. But then, also, the motivations of artists, buyers, and viewers are mixed.

While he writes that the project of colonialism, in encountering native peoples, had to continually adjust to continue its dominance, sometimes to the point of confusion, he also notes the more positive aspects of adjustment on the Indigenous side. From Albert Namatjira to Papunya to Gordon Bennett, we see how Indigenous artists have taken from Western culture, and this is not merely evidence of assimilation, but a use of borrowed styles to assert sovereignty, and evidence that Indigenous cultures are strong through their adaptability.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.