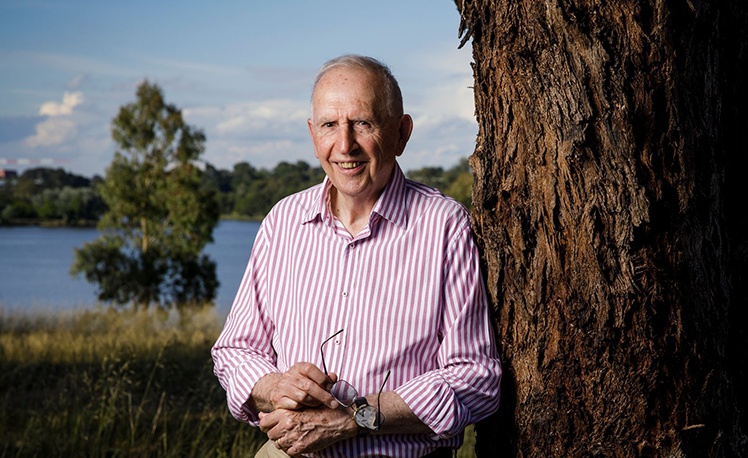

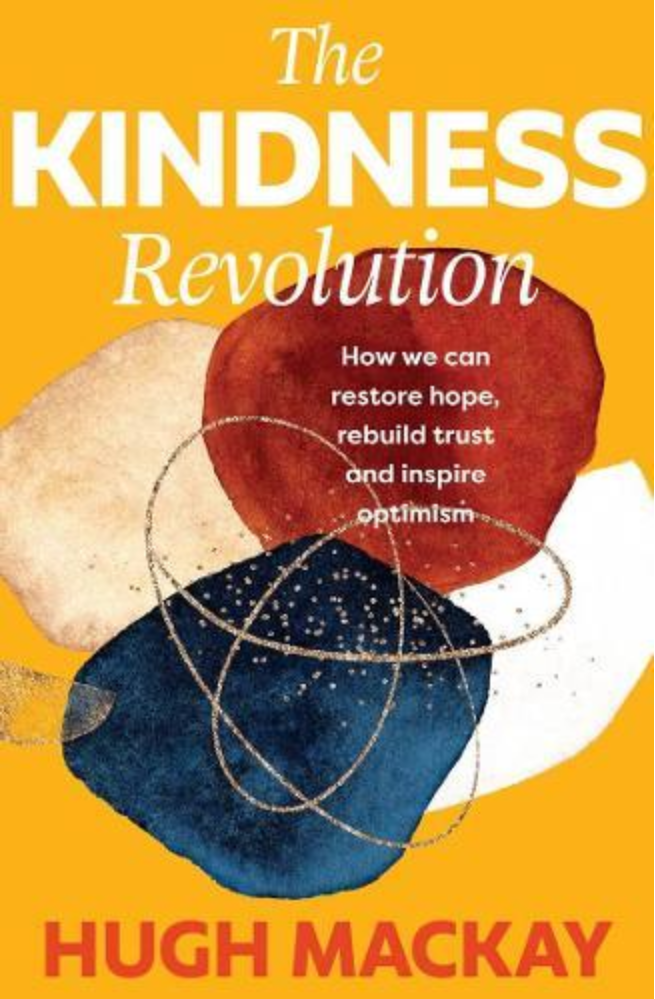

Reviews: The Kindness Revolution, The Inner Self & The Question of Love by Hugh MacKay

It seems that during lockdowns Hugh Mackay was busy – writing not one, not two, but three books, all concerned in their own ways with wellbeing and a cohesive society. These are typical subjects for Mackay, and indeed The Kindness Revolution promotes harmony through cultivating relationships and community. The pandemic provides a jumping-off point; he hopes it may be a spark for a revolution in the way we conduct ourselves in society, building on the way the pandemic has forced changes in perspective.

A revolution often starts at the grassroots, not with pronouncements from leaders but in everyday life, and while the news during the pandemic has been full of rule-breakers and the arguments of politicians, the majority of people have done the right thing. We have made sacrifices in order to protect the vulnerable and have focused on work/life balance. All this, says Mackay, is a template for how we can live in future.

Kindness is not exactly trendy, and love is not something most people would put at the top of their list of quintessential Australian values (mateship, larrikinism, easy-going perhaps?). But the pandemic shows cooperation can be bigger than competition and individualism, if we accept it as the norm, or a worthy goal. In Australia, we have typically seen ourselves as a lucky country, but with application and wisdom it is possible to be a loving country, writes Mackay. As elsewhere, he seeks out our better qualities, showing how we can harness them for reconciliation and care.

He is pragmatic about life being messy and sometimes irrational, arguing that we need to be resigned to the way life is, but then listen, apologise and forgive. He warns against cynicism, but interestingly, disagrees with journalist Julia Baird, who, in her popular book Phosphorescence, advises us to run from cynical and selfish people. (To be able to do so perhaps says something about Baird’s status.) Mackay says that while we shouldn’t emulate them, we should love them, recognizing that some with unhealthy attitudes to life need care. (This, of course, aligns with what the churches teach, and is grounds for moving beyond cynicism to hope.)

Cynicism and pessimism can also grow through lack of attention to self. Of course, there is not a neat separation between the inner and outer self, but in the book The Inner Self Mackay concentrates on how we see ourselves – on individual psychology, in other words – in contrast, he says, to most of his other work, which is about how we relate to society.

Many of us are reluctant to own up to our true selves (and our culture is geared not towards honesty but to a constructed, flawless façade we need to present). Self-analysis is hard work, frankly. There are things that skew our inner self that we need to confront: selfishness, self-delusion, the pursuit of happiness or material wealth, work pressure, dishonesty about the past. Mackay offers gentle advice on dealing with these and nudging ourselves towards an inner core that is honest, balanced and focused on others.

This orientation to others is key to Mackay’s outlook and stands in contrast to much pop-psychology self-help that focuses on self-fulfilment. Although talking about the mental or moral health of individuals, Mackay recognizes, even insists, that the social is at the heart of the self. We are a social species and our ‘capacity for love’ is what makes us whole.

Both of the above books have fictional vignettes embedded in the text, where Mackay explores how the principles he discusses may work out in practice. The Question of Love is an extended version of this – a novel – but where in the other books Mackay tells us what to do, The Question of Love is more a lesson in what not to do, or at least in how life complicates good intentions.

In musical terms, his other books are melody, this one is harmony – it shadows the other books, at times even as a discordant counterpoint, in order to add depth to the issues with which Mackay is concerned. Mackay explains that his novel is inspired by musical ‘variations on a theme’, in the music of Bach in particular, where a melody line is repeated but embellished, explored, thrown into relief by harmony lines. So here the opening ‘theme’ is an architect husband coming home to his violinist wife. In a bold structural move, progressive chapters return to this theme, Groundhog Day-style, and Mackay subtly changes the tone of the encounter, adds detail, fills in the backstory. He has some fun with stereotyping well-off, inner-suburban Sydneysiders, but also explores the faces we put on in relationships, how we talk past each other and misinterpret, remember differently, and project our feelings, wishes and motivations on to those we love. And, as in his other books, this is a reminder of the power of listening, to both others and ourselves.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.