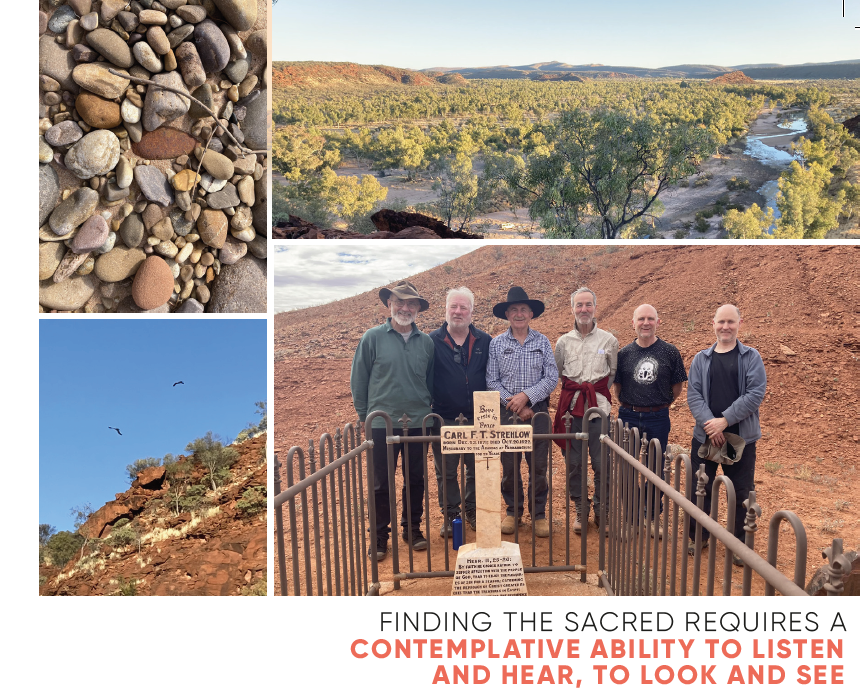

From 24 to 31 July, a desert pilgrimage group walked along the oldest river on earth, the Finke in Central Australia, known in the Arrernte language as Larapinta, or Salty River. We were there to mark the centenary of the death of Lutheran missionary Carl Strehlow and to celebrate his achievements in supporting and documenting the living culture and language of the Arrernte people. As well as his ground- breaking anthropology research, Strehlow directly protected Aboriginal people from threats of massacre, building up the Hermannsburg mission as a sanctuary of respect for Aboriginal dignity.

The Larapinta/Finke headwaters are in the Tjoritja mountain range (the West MacDonnells) in the Northern Territory. The river runs past Hermannsburg/Ntaria, and ends in the dry sandy lands of the Wangkangurru people in the Simpson Desert (language map). The ancient geology and ecology of this spectacular region provide windows into deep time, in a watercourse that has flowed through the same valley for about half a billion years. So too, the indigenous names of the mountains and waterholes are very old in human terms, shaping sacred songlines that have provided meaning and memory in this place for many thousands of years. On top of these layers of complexity, recent history since white settlement in the late nineteenth century has brought this isolated country into connection with the modern world, creating much sadness for its indigenous people.

Rev. Carl Strehlow was pastor at Hermannsburg Mission for 27 years between his arrival with his young wife Frieda in 1894 and his death on 20 October 1922, apart from one year taking his children back to Germany in 2010. The poignant drama of his final days was told by his son Ted in the renowned book Journey to Horseshoe Bend, describing the family’s desperate but unsuccessful effort to go by horse and buggy down the Larapinta/Finke toward medical help in Adelaide. The journey ended in tragedy, at a time when faster travel in this remote region was almost impossible.

The legacy of Strehlow’s achievement is seen in the Strehlow Research Centre in the Museum of Central Australia, which houses sacred secret tjurunga objects given by Arrernte elders to Ted Strehlow for safeguarding. While controversial due to some breaches of trust and questions over access, this priceless collection enables elders to continue their living cultural practice in ways that might be impossible if it did not exist.

Uniting Church Minister Rev. Dr Mel Macarthur organised our walk. Rev. Dr Macarthur is now completing a PhD dissertation on Strehlow’s journey, seeing our partial repeat of it as a type of Australian pilgrimage that can help to bring together white and black histories to promote a message of reconciliation. Unfortunately, Mel fell ill just before our departure and was unable to do the walk.

The walkers were Uniting Church members Rev. Dr William Emilsen, Bill Tulip and Robbie Tulip, Lutheran Church member Martin Reusch, and Professor Hart Cohen of Western Sydney University, who is making a film about it. Two support vehicles were driven by cameraman Rob Nugent and long-time Central Australia resident Glen Auricht. Glen has lived in Central Australia for fifty years and speaks Arrernte. He was our guide, sharing some remarkable stories along the walk about the spirit of place and cultural context, especially at the permanent waterholes that used to be home to large indigenous communities. Locals David Hewitt and David Moore also joined us for part of the way. Invitations were extended to the local indigenous community, but none took part.

We started at Hermannsburg/Ntaria and walked a total of 70km along the Larapinta/Finke in the path of Strehlow. Unlike his rough journey of pain and sickness and fear of death, we were supported by four-wheel-drive vehicles carrying our bags and camera gear. For the first few days there was not a cloud in the sky, and at night the desert stars were stunning, providing great opportunity to tell stories of the constellations. The clouds came in on our fourth day. No animals were to be seen apart from birds in the sky and fish in the waterholes. At night we heard the neighing of horses and howling of dingoes. One point of sadness for threatened species is how the invasive buffel grass, the cane toad of arid regions, has killed off native animals by removing food and shelter. Buffel is now throughout the more fertile soils of the Larapinta/Finke valley. It has outcompeted the fragile native grasses and killed trees by burning too hot.

The Larapinta/Finke had a ten-metre flood in the big rains in February this year, so there was a lot of debris high in the trees, and enormous amounts of firewood, which gave us some crackling campfires. The floods usually run out in the Simpson Desert, but we heard some of the water this year reached Lake Eyre.

The pebbles in the riverbed are a rainbow array of different colours, reflecting the many geological sources that have contributed to the river over hundreds of millions of years, washed down from the mountains from before plant life emerged on land.

We heard these large rocks symbolise a story of the key importance of sharing food in traditional culture.

Our walk ended at Irbmangkara (Running Waters), just part of the distance of Strehlow’s journey. We then returned by bus to Alice Springs/Mparntwe and the next day drove six hours to Strehlow’s riverside grave at Horseshoe Bend on the edge of the Simpson Desert, where we completed our pilgrimage at a commemoration service with the local community.

The presence of God in guiding and blessing our pilgrimage in the heart of Australia emerged in conversations along the way and around the campfire, in the spirit of place of the beautiful ancient river gorges, and in the warm feelings of the local community toward remembering the work of Carl Strehlow.

Our pilgrimage honoured Strehlow’s achievement as a martyr for indigenous reconciliation. He remained in Hermannsburg after he fell ill due to his passionate commitment to the people, staying true to his calling to mission. His legacy shows the important ongoing role of Christian faith in both supporting and challenging indigenous identity and culture, through a ministry of reconciliation, seeking a completely honest and open understanding of the difficult situations facing indigenous people today.

Pilgrimage is a journey of reverence where we can cultivate a sense of awe and wonder for the holy. Finding the sacred requires a contemplative ability to listen and hear, to look and see, to enter dialogue and put thoughts into a coherent story. Ancient ideas of pilgrimage have lost meaning for many people due to the confusion that surrounds religion. A new meaning for pilgrimage can bring together all the different sources we encounter along the way, in the effort to understand and explain the spiritual meaning we find on the path. Pilgrimage can integrate the heritage of wisdom with new experience in a spirit of respect for sanctity in nature and culture.

Our pilgrim journey to Horseshoe Bend considered four themes raised by Ted Strehlow’s book:

- awareness of Carl Strehlow’s pietistic calling from God with his strict Christian theology;

- the rich cultural depths of indigenous people with their difficult modern realities informed by the ancient dreaming songline heritage;

- the flawed but honourable outback settler culture; and

- the beautiful and rugged natural environment of the Larapinta/Finke River.

In different ways, each of these themes invites us to explore how time connects to the eternal, how our world connects to God, and how Christianity can evolve to integrate and recognise local cultures.

The preamble to the Constitution of the Uniting Church in Australia states “The First Peoples had already encountered the Creator God before the arrival of the colonisers; the Spirit was already in the land revealing God to the people through law, custom and ceremony. The same love and grace that was finally and fully revealed in Jesus Christ sustained the First Peoples and gave them particular insights into God’s ways.”

Walking the Larapinta/Finke River in a spirit of pilgrimage helped us to reflect on the indigenous encounter with the same divine presence we see in Christ, within their own distinct cultural traditions. In this context, the complex spiritual order of God at the ground of Christian faith can acquire a new and deeper light, bringing together contrasting approaches as we work toward an integrated understanding.

A transformative theme in our discussions was around the essential role and beauty of indigenous language. The philosopher Martin Heidegger said language is the house of being. In the context of the Larapinta/Finke river, the ancient indigenous language of the Arrernte people speaks to the identity of place and culture and their unique sense of being in ways that simply cannot be understood or translated in other languages. Our story of being, with the ethical values that emerge from that story, is embedded in our own language, and can be deepened and enhanced by respect for the wealth of difference in other cultural traditions, approached in a spirit of pilgrimage.

Robbie Tulip, Secretary of Canberra Region Presbytery of the Uniting Church

1 thought on “A Reconciliation Pilgrimage ”

I preached at Leura Uniting Church to mark the Strehlow centenary on 23 October. Here is my sermon. (five minute read)

Atonement

Good morning. I acknowledge indigenous elders and all indigenous people, and the suffering and sorrow and silencing they continue to experience. I thank the reverend Mel MacArthur for his kind invitation to participate in today’s service to commemorate the legacy of Carl Strehlow on the centenary of his death. My comments will focus on the theology of atonement and repentance.

Atonement is an ethical and moral concept that means being at one. It describes a situation of reconciliation, where a damaged relationship is healed. In Christianity, the death of Christ on the cross is held to atone for the sins of the world, repairing our broken connection to God and bringing humanity into unity with the earth and the cosmos.

Our walk down the Larapinta River (known as the Finke) in July provided time to reflect together on how badly modern Australian history has harmed the cultural and natural life in this beautiful fragile place. The ancient living systems of the Larapinta have a complex and priceless sanctity that we should hold as of infinite value. Instead the Australian nation has held this heritage as of little worth.

We should reflect on how Christian faith can enter the ethical conversations about the need to atone for the destruction of our irreplaceable cultural and natural heritage.

How can the atoning sacrifice of Jesus on Golgotha relate to the broken relationships of Central Australia? We are far from the integral peace of atonement. In atonement we are all at one with the whole of creation. Jesus tells us in The Last Judgement at Matt 25 that we will remain in a state of disruption and division until we transform our social values to give the highest esteem to all who are excluded and marginalised and damaged by the evils of the world. We must treat the defenceless and vulnerable and innocent as though they are Jesus Christ himself.

As we mark the centenary of the death of Carl Strehlow at Horseshoe Bend, we can ask about his vision of atonement. The courageous work of both the Reverend Carl Strehlow and his son Ted to document and honour the ancient living culture of the Arrernte people of Ntaria is part of an atoning journey of healing for Australia.

But atonement faces a major blockage. Unrepentant racism continues to blight the lives of Arrernte people today. The journey toward atonement for the destruction of indigenous culture and ecology has barely begun, and will be the work of many centuries.

The Larapinta is the oldest river on Earth, flowing through the same stable geology for the last half billion years. The old river was formed before plants emerged from the sea. Ever since then, its ecosystems have evolved into ever more complex interrelationships, punctuated by occasional catastrophes including at present. We should hold natural and cultural complexity as sacred, as a window upon eternity, as a revelation of how God supports the orderly flourishing of life on Earth.

Australia’s white settler society has a heedless and unrepentant arrogance about our destruction of Australia’s ancient natural and cultural complexity. This refusal to repent is a main barrier to the respectful dialogue needed for atonement. In this context, it is valuable to consider what the Bible had to say about repentance. John the Baptist tells us in the story of the baptism of Christ that repentance is essential to obtain forgiveness. When you have done wrong, you have to be sorry in your heart in order to restore right relationships. You must understand that you have done wrong, why it is wrong, and the harm your action has caused. That means that while a society remains in denial of its state of sin, which is largely the case for Australia’s history of genocide and ecocide, that society also remains unforgiven by God. Our mental and physical health requires a path to atonement.

The love of God is infinite and unconditional, but the Gospel tells us that divine forgiveness is conditional upon repentance. To restore our relationship with God requires an atoning sorrow, a recognition how actions that benefitted us came at great cost and loss for others.

And such restoration is essential, for otherwise we worsen the division and delusion and suffering of our society, living under what the Bible calls a state of divine wrath.

Jesus tells us in the Beatitudes ‘blessed are those who mourn for they shall be comforted.’ We can hope for the comfort of atonement as we mourn the violence of Australia’s frontier wars. Grief over historic loss generates a need to understand its ongoing effects and to encourage broader social repentance for the sins of our society, leading to reconciliation, recognition and respect.

The Indigenous Voice to Parliament will deepen religious conversations about Australia’s need to atone for the evil deeds of the colonial period and the enduring traumatic legacy of the violence of conquest.

Yesterday the Uniting Church held its first indigenous theology conference. I put a question to the distinguished indigenous theologian Aunty Anne Pattel-Grey about her views on repentance and atonement. Aunty Anne responded that white Australians need to walk alongside indigenous people as equals. This means our situation can still be redeemed, but only if we challenge and transform dominant social values that promote division and injustice and inequality.

The ancient natural beauty of the Larapinta River is a sign of the abundant loving grace of God. Our pilgrimage of reconciliation along the Larapinta showed how fragile and sensitive its ecology and human culture are today.

We have a religious duty to atone for the sins of our society in order to repair the damage we have caused. As Christ prayed, may we all be one. Just as Christ bore the sins of the world, the church today has an atoning mission of healing and restoration. Only a rigorous and resolute honesty about our true situation can open the path toward atonement.

Let us pray. Loving eternal God, we give thanks for your incarnation in Jesus Christ, who suffered and died under the Roman Empire as indigenous Australians have suffered and died under the British Empire. We pray for the Larapinta River, for its people, climate and biology. We pray for the day when our world will be at one with you, through the glorious grace of your Son Jesus Christ, whose death on the cross began the atoning work that we are called to continue today. In the name of Christ, Amen