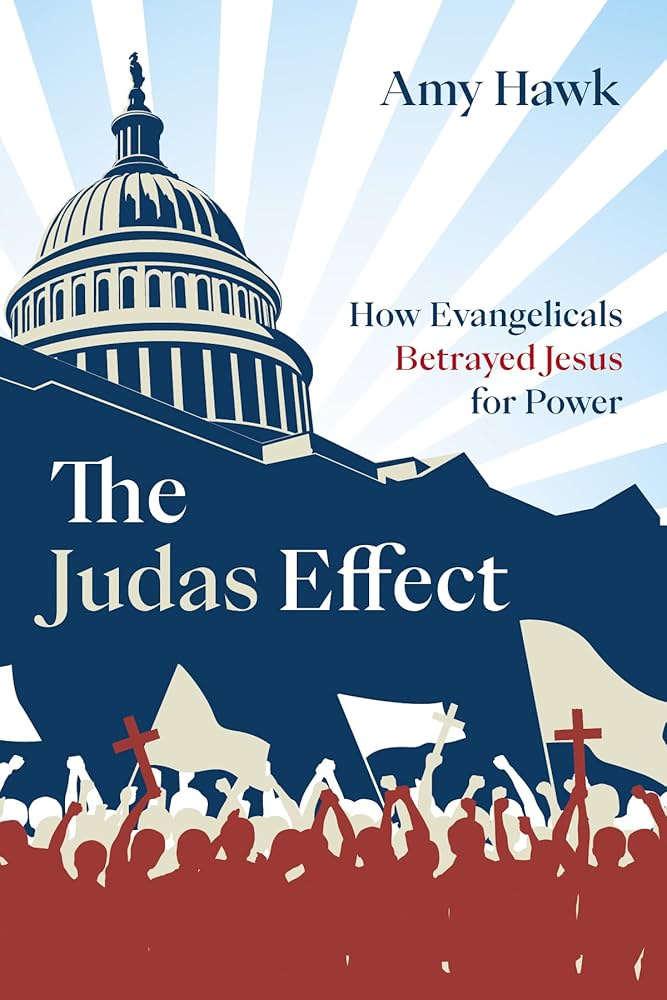

Review: The Judas Effect: How Evangelicals Betrayed Jesus for Power, Amy Hawk, Cascade Books

From the perspective of someone outside the USA, it is hard to understand the popularity of Donald Trump amongst half the American population, who think not only that he is good for the country, but also that he is chosen by God. That Trump is supported by the bigoted and bitter is not surprising, but why does he have such support amongst people who claim to be passionate followers of Christ?

After-all, Trump is a narcissist who ridicules veterans and people with disabilities, a complainer who cares nothing for human rights, an adulterer who has bragged about sexually assaulting women, a pathological liar whose only goal is winning, and a conspiracy theorist – when it suits him – whose incompetence cost thousands of lives during the pandemic. Bob Woodward wrote in his books on Trump that while Trump thinks of himself as a genius, he is in reality uninformed, unwilling to plan or listen, immature, divisive on purpose, ‘chaos’ personified.

Amy Hawk and her husband were (lay) church leaders whose evangelical world was shattered when fellow evangelicals supported ‘cult’ leader Trump. In her book she describes a few key incidents that, as she puts it, popped her bubble: during a worship service she realised she and her fellow congregants worshipped different gods, prompted by an anti-immigrant Facebook post from one of the band leaders, and she was sickened by Trump’s making fun of a journalist with a disability.

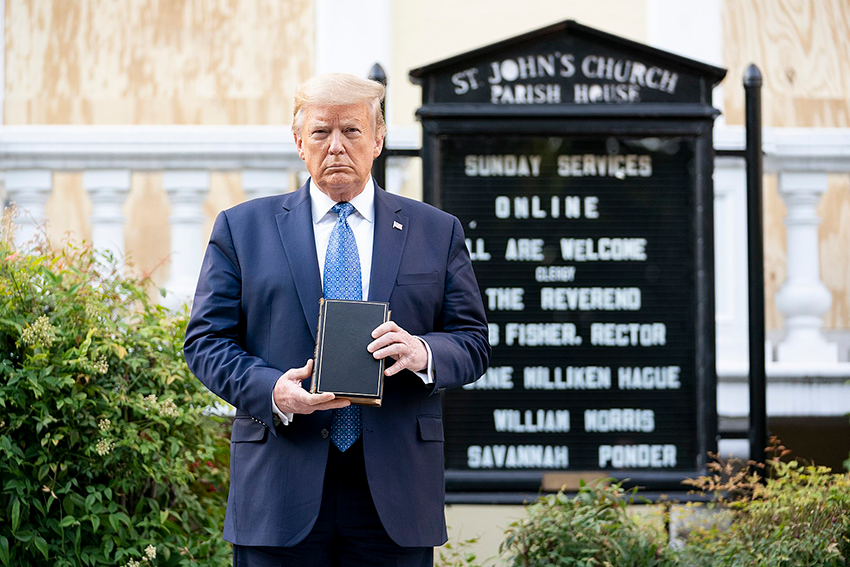

She looked on with horror as evangelical leaders bowed to a man who praises Putin for killing reporters, fans his followers’ hatred, encourages violence and spreads lies. She notes his unethical and illegal business practices, his own racism and encouragement of racists (his recent questioning of Kamala Harris’s ethnicity being only the latest in a long line), his mistreatment of women, especially those who dare to disagree with him, his disregard for the law, democracy and biblical ethics.

Hawk writes that the rest of the world is not fooled by Trump and see him as unhinged and untruthful. Evangelicals either overlook or embrace his odiousness because, says Hawk, they have been intoxicated by the potential of gaining political power. Evangelical leaders want political access to achieve what they think is the Lord’s work. Hawk’s book is a message to her fellow evangelicals that church support of Trump is to their detriment.

The Bible, she explains, has scores of warnings against leaders like Trump. If we want to take seriously for a moment that there is even a debate about Trump’s compatibility with Christian values, we might look to 2 Timothy, which warns against arrogant lovers of money and themselves without self-control. The letter goes on to warn readers against those deceitful leaders who pretend to be religious. Jesus warns his followers to be on the lookout for false messiahs who say, ‘I am the one’. Hawk notes darkly that Trump’s language is very similar to this, and to that of Hitler, with Trump saying, ‘I alone can fix it’.

When patriotism and faith become entangled, as they are in the US, there is a tendency to want to gain political power to force Christianity onto the nation – a problematic notion. Hawk points to Jesus’ warnings to his disciples to not go down the route of fighting for political power, as power corrupts. Political supremacy won’t lead to anything resembling the Christianity of the early church, and the danger, as Hawk argues, is that evangelicals will simply become more like Trump.

Hawk doesn’t go into much more depth in explaining Trump’s evangelical popularity except for an evangelical lust for power. But there are complexities amongst evangelicals in their support. Many evangelicals equate Christianity with conservatism, and the Democrats with virtual atheism, and therefore default to Republican support, no matter the candidate. Some naively see Trump as a sinner being used by God. Linsey McGoey recently reported on the London Review of Books blog that many evangelicals and Republicans are not fans of Trump (‘egotistical maniac’ being a not-atypical description) but see no alternative. (On the other hand, there are evangelical Republicans who will not vote Republican specifically because of Trump.)

From the perspective of outside, we might also observe deeper problems with American evangelicalism than simply misguided political support of Trump. As Hawk hints, within American evangelicalism there is often a conflation of worldly success and Christian faith, expressed in militaristic and dualistic language, the prosperity gospel, emphasis on congregation sizes and buildings, book sales, media exposure, global reach and, most worryingly, a tendency to hypocritically cover up scandals and failures. In this sense, there may be less incompatibility between what has become American evangelicalism and Trumpism than at first it might appear.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.