Review: Cloven Country: The Devil and the English Landscape, Jeremy Harte, Reaktion

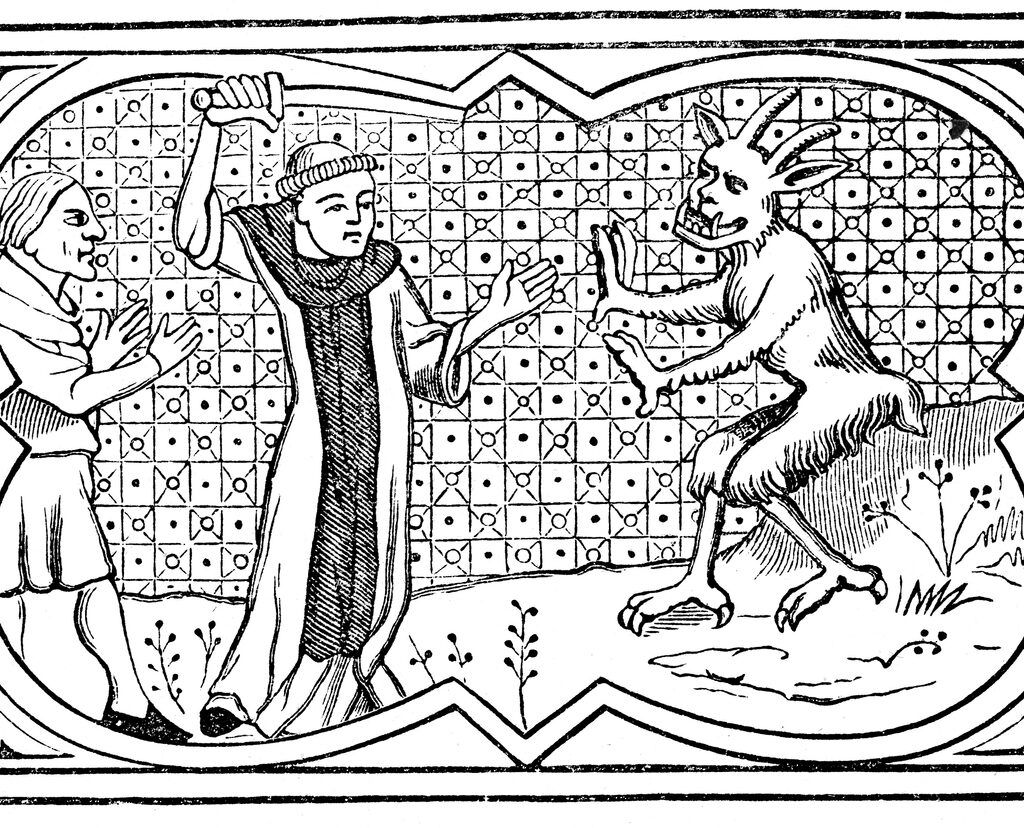

As Christianity spread across Europe in the wake of the Roman Empire it transformed older stories to give them a Christian twist. God, though, was a fairly distant figure, and it was the Devil that occupied people’s thoughts and fears. He was lurking behind every hedgerow, in both a spiritual and physical sense.

Landscape features were renamed for the Devil, malevolent forces and calamities were blamed on his ubiquitous presence. Curiously though, in Jeremy Harte’s book we see how the Devil’s ubiquity in folklore consequently meant that he had a confusing, contradictory and ultimately entertaining number of manifestations. He appears as a well-dressed and enigmatic gentleman, or a monster. He is secretive and boastful. He can be a giant but is easily tired. He can be scary, but in many stories he is certainly not the equal of God, and is mostly not even the equal of human beings.

In the same way that ammonites (fossil seashells) were explained away as being the Devil’s toenails, in the premodern world, hills, potholes in rocks and other features were given supernatural, devilish explanations. If a feature was given the name ‘Devil’s something-or-other [insert type of feature]’, possibly because it was large, forbidding or in some other way significant, it accumulated an explanatory folktale.

In East Anglia, where there are many Devil’s Ditches, the Devil is a giant labourer, and, like gods in other cultures, or like the Rainbow Serpent, he is responsible not for mischief but simply for giant earthworks. But in the developed tales, the Devil’s chief responsibility is mischief. There are many stories of cursed fields or abandoned churches wherein townsfolk work hard all day on a task, only to find that, in the morning, all their good work has come undone. The Devil was particularly keen on ridding the countryside of church bells. One can read into these stories meaning-making for natural disasters or otherwise unexplainable catastrophes.

While the Devil was often portrayed in some stories as having superhuman strength, in many stories, despite his mischief-making, the Devil is easily discouraged, and surprisingly dim-witted. In one story, the Devil is tricked into sparing a town because he is convinced by a local he meets on the road that the target town is too far away. In another, he digs a giant ditch (near Brighton) to let in the sea and drown the valley, but an old woman hears him working and puts a candle in her window. The Devil sees it, thinks dawn has come and abandons his work. (In these stories he fears the sunlight, like a vampire.) He may be a trickster, but he is easily tricked. In some stories he is oddly ignorant of human ways, even anatomy, which is odd since he is meant to be a wily, constant tormentor of people. But what sits behind these tales is the need for human beings to gain the upper hand psychologically against an often-confusing world.

In a kind of deus ex machina, the Devil’s plans can unravel with the simple appearance of a clergyman or a word of prayer. Of course, the Devil of Christendom is after souls. Many tales feature mortals making rash promises which they can’t get out of without the intervention of a priest. Yet, in some stories, Harte notes, as the clergyman is dressed in black, there is a strange resemblance to the Devil. In some stories, while they move about in similar circles, it takes a witch to defeat a Devil.

While many tales Harte recounts are humorous, there are the scarier ones, similar to the dark folk tales of Eastern Europe. In some of these stories souls are not rescued, but mostly they are morality tales, scaring townsfolk, particularly youthful ones, out of scandalous behaviour, such as partying on the Sabbath. Others suggest that, as in the pre-Christian world, some particularly forbidding places, especially at night, were thought of as more permeable to the diabolical world.

Harte emphasises that folktales evolve. What was attributed to demons in medieval times later became attributed to one Devil. By the 1700s Protestant England saw a shift, with more emphasis on misfortunes being attributed to an omnipotent God who was punishing sin, rather than to a mischievous Devil (though this is not a simple demarcation). The Devil became Satan, not stealing sheafs of wheat, but more sinister, corrupting hearts. Today, while Christian faith remains prominent in England, it seems belief in the Devil of folklore has somewhat gone the way of the troll and the leprechaun.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.