Review: The Book of Job: A Biography (Lives of Great Religious Books), Mark Larrimore, Princeton.

The Book of Job seems apt for our times. Then again, it seems apt for any time. The question of suffering is perennial, not just in the matter of Job’s woes, but in the general state of a flawed world. Job throws up more questions than answers: where is God in the midst of suffering? Is suffering part of his plan? How much can we understand his plan? Is God omnipotent? Does God reward the good and punish the bad? Where does evil come from?

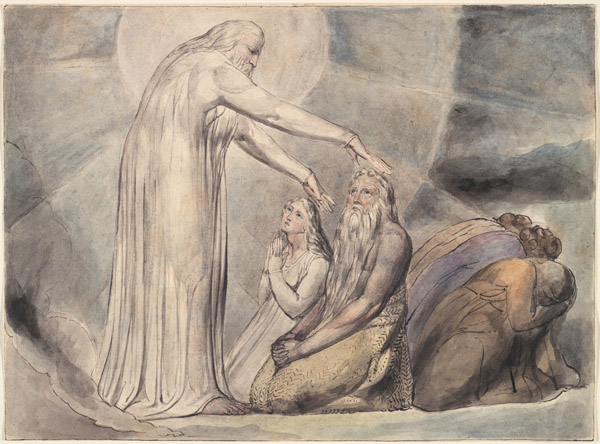

The Lives of Great Religious Books series focusses not just on a book’s content but also on how it was originally written and how it has been received over centuries, including in art and other literature. In the case of biblical books, the series takes them somewhat as stand-alone entities, and indeed the Bible is a collection of books of different ages, genres and emphases, but one of Mark Larrimore’s points is that Job should be read in dialogue with the rest of the Bible. This has been normal Christian practice, to interpret books in the light of other books. Medieval glosses helped readers read Job simultaneously with other books. The Christian Church has generally seen the Bible as a web of connections. The earliest interpreters read Job in minute allegorical detail, though in the case of Job’s mention of a redeemer, the Church has generally thought of this as more directly pointing to Christ.

But within Job itself there appears incongruity. The scholarly consensus is that Job had more than one author, which explains, among other things, why God ‘comes barging in’, as Larrimore puts it, and doesn’t answer Job’s questions. On the other hand, a minority of interpreters see it as the work of one author of genius who has encapsulated within the text the fact that life can seem disjointed and, at times, lacking meaning.

Job of course is part of the wisdom collection (which includes Psalms, Proverbs and Ecclesiastes), containing a certain pessimism, or realism, depending on your point of view, about the ways of the world. Job in particular is a spanner in the works of the Israelite idea that one can trace a clear line from the faithfulness of a person to their material riches. For Elie Wiesel, the tacked-on (happy) ending where Job is restored is a cop-out. Even for the faithful, life simply sucks sometimes.

Robert Frost said lack of meaning was the book’s meaning. Similarly, G K Chesterton, characteristically, found paradox in Job being enlightened by his acceptance of his incomprehension of God’s ways. The philosopher Immanuel Kant said that Job shows that the world can’t make sense on its own (a sentiment sometimes backed up by the observations of evolutionary theorists), and being honest about a lack of clarity provides philosophical clarity. For the Romantic movement, God’s unknowability is part of his sublimity and grandeur (a point God himself makes in Job). These interpretations are not limited to modern times. The earliest Christians took seriously the message that bad things happen to good people and got on with the job of helping the poor and widowed, instead of philosophising.

But central to Job’s story is a struggle against the seeming injustices of life; he is not simply passively accepting. Simone Weil memorably described Job as like a live, struggling butterfly pinned to the page. Larrimore notes that the idea of ‘the patience of Job’ is not always borne out in a reading of the text, unless rage at things is somehow patience.

For Kant, and for much modern ethics, Job initiates the idea that empathy for one’s fellows is more important than meaning, and the lack of predictability or sense of where evil strikes is perhaps a prompt for more ethical behaviour. This is traditionally what the Church does. Sure, theologians work busily on the problem of theodicy, sometimes sounding like Job’s friends, but most Christians (not to mention doctors and nurses) are engaged in the process of not accepting suffering by finding practical ways to alleviate it.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com