Lately I have been in some conversations relating to the language we use. We all speak English; a number of us speak or read another language, or languages, in the course of our days. But mostly, in most situations, we use English.

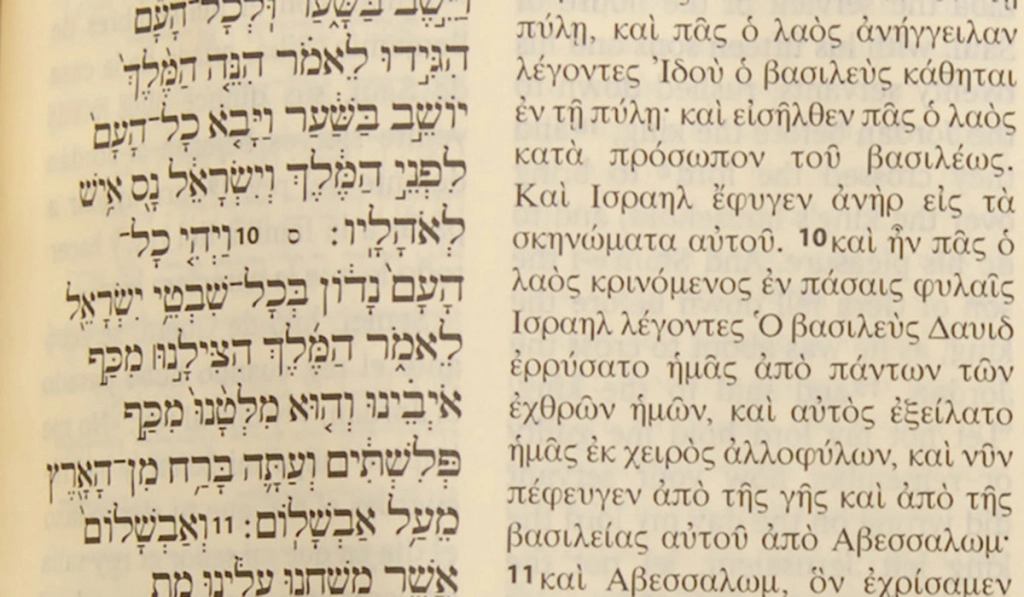

For many years, much of my work was focussed on making sense in the English language of material that was written in another language. The books of the Bible, as we should know, were not first written in English. Our Bibles are translations from Greek, in the case of the New Testament, and Hebrew (and a few chapters of Aramaic) in the case of the Hebrew Scriptures. So choosing the right words to render those foreign language texts into our English language is an important task.

Indeed, when it comes to Bible translations, we have allowed the Enlightenment to drive us into an incessant search for The Right Word/Phrase/Translation. Since translating is a skill that relies on nuance and subtlety, the offer of multiple options is just too good to refuse—and it invites us to explore, to question, to search for ourselves. That can only be good for our own discipleship and faith development.

These days, my work is focused more on other areas where language matters. Sure, I still am involved in Bible studies where the meaning of a particular word or phrase in a biblical book might be a point of consideration. But more often during the week, I am involved in conversations where I am listening to people speak in the words and the phrases of their own choosing.

My task in such conversations is to listen carefully, to seek to understand what is being said by my conversation partner. Grasping the words that are spoken and sensing the meaning of what is being conveyed are important processes. We all do it when we converse. In ministry, listening carefully, hearing and understanding correctly, are vitally important skills.

Another area where understanding the words used—and making decisions about what words to use—is worship. I have long been of the practice that I will try to choose hymns and songs that don’t include complex, inscrutable, incomprehensible words—theological jargon, in particular. (To be honest, sometimes, if I really want to use such a hymn or song, I will “translate” such terms into more manageable words, and put them into the lyrics on the screen—although nobody seems to notice!)

I also have a personal dislike of hymns that persist in using “thee” and “thou”—fine, common words in Shakespearean English, but not at all in common use in the 21st century! A simple change from “thee” to “you” is easy and clear. The same goes for verbs that end in “-est” and “-eth”, like “thou doest” and “they saieth”. They are strange to people listening with a 21st century ear and not readily understandable in the contemporary context.

The matter becomes a little more complex when thinking about other terms often found in traditional hymns—and even in contemporary choruses. Persistently calling God “he” and referring to human beings as “men” really grates with me—and has for half a century, now. Using inclusive language is the policy of the Uniting Church, and that should carry into our hymns and songs in worship.

Likewise, I avoid hymns or songs that reflect particular theological viewpoints that I don’t personally adhere to (like hymns glorying in the shed blood of the lamb and extolling him as the

substitutionary means of atonement for our terrible sins). We can sing about how we relate to Jesus without adopting medieval theological terminology that has “stuck” in some quarters of the church long beyond its use-by-date.

In the same way, we can seek out those songs, poems, and prayers that move away from the stultify ing predictability of calling God “Father” or “Lord” over and over, never deviating from these so-called “biblical” names for God. Why, there are many names for God that are found in scripture—Holy One, Righteous One, Eternal One—and a proliferation of terms that identify a quality of God—Gracious God, Loving God, God of justice, Compassionate God, Faithful God, and so on.

There are also ways of addressing God that have been developed more recently—Ground of our Being, and the variant threefold pattern of “Creator, Redeemer, Sustainer” come to mind. And I recently found someone, writing about our care for creation, referring to God as “Gardener God”. I like that! Surely we ought to rejoice in the diversity of divine names that we have at our disposal.

And another pet peeve I have is the way that some grand favourite hymns simply assume that we are in the northern hemisphere; that Easter is taking place when the temperature is warming and the flowers are budding; that Christmas is celebrated at the time of the year when days are shortest and temperatures are coldest, with snow on the ground and warm fires burning.

That’s not my experience, and it feels weird to sing as if it is, when it isn’t! There are Southern Hemisphere alternatives that can be sung—not just “The north wind”, but many others that have been written downunder in recent decades by writers such as Shirley Erena Murray, Colin Gibson, Robin Mann, David MacGregor, Craig Mitchell, Leigh Newton, Heather Price, Malcolm Gordon, and more.

We have, in our midst, some fine wordsmiths who write new songs for us to sing—songs that use contemporary words, that avoid theological jargon, that employ inclusive language, that relate to a contemporary “downunder” context. People have always created new songs, and they still are today. Fostering that creativity by singing these songs and hymns is good to do.

There are also talented folks who are able to revise the words or even craft new verses for existing hymns, maintaining the traditional beloved tunes, but inviting people to sing using words, concepts, phrases, and ideas that more readily reflect the natural way of conversing and speaking in daily life.

I’m thinking of Sue Wickham and Sarah Agnew within the Uniting Church; I am sure there are many more. Sarah writes fine poetry for use in worship; and when it comes to poetry, the work of Jason John is excellent, also—although not always geared for liturgical use. (And there’s often a language warning with Jason’s work!)

That’s a good thing, I believe; articulating the Gospel in ways that make most sense within the context is an important thing to do. It’s perhaps somewhat akin to paraphrases that people make of biblical passages—or, indeed, preaching, where the aim is to communicate the message of scripture in ways that connect into the contemporary context.

Sadly, I know not everyone shares my interest and delight in discovering “new words for old tunes”. Some people think that the ”traditional” words shouldn’t be changed or interfered with in any way. However, if the original is acknowledged as the inspiration for the reworking, then I think that should be acceptable; it indicates that the person reworking the old hymn is finding inspiration to express in refreshing and invigorating ways, the age-old truths of the Gospel.

And really, this is actually doing what many fine hymn writers of the past have done—they reworked their own words, they reshaped verses from other writers, they wrote whole new sets of verses for tunes that were popular in their day (although they weren’t bound by the laws of copyright as we are). It’s part and parcel of the fine tradition of hymnody that we celebrate within our church.

So choosing the right words is a very good thing to be concerned about. What language shall we use? The language that conveys our faith in relevant, understandable, enlivening ways, right here, right now! I’m all for that.

Rev. Dr John Squires is Presbytery Minister (Wellbeing) for Canberra Region Presbytery and the Editor of With Love to the World. This reflection originally appeared on his blog, An Informed Faith.