Douglas Purnell is curator of the Stations of the Cross exhibition in Sydney and Canberra. He is passionate about bringing a well-known historical tradition into a contemporary setting that allows people to reflect on the last hours of Jesus Christ’s life, from a unique and creative perspective. Notably, Douglas is keen to point out the importance of the exhibition as a community event that engages Christians and non-Christians alike.

What began as a personal creative and spiritual inquiry for Douglas became an exhibition that has grown to include local and international artists.

This year, the exhibition will be held in the Sydney suburbs, at Northmead Creative and Performing Arts High School, as well as at Canberra’s Australian Centre for Christianity and Culture.

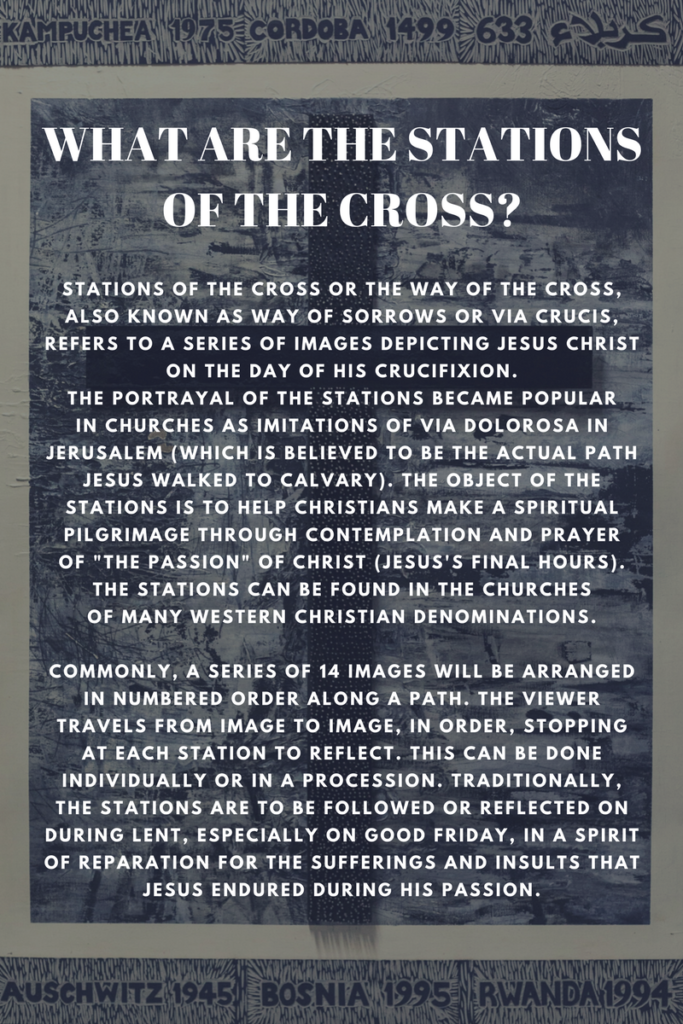

“Historically, the Stations of the Cross date from about 1200. Up until about that time, Christians had made a pilgrimage back to Jerusalem to walk the way of the cross at Via Dolorosa, which marks the Stations of the Cross,” explains Douglas of the historical significance of the Stations.

“St Francis of Assisi, who I now think is an incredible educator, said that because the church had spread so far and it was difficult to make the journey back to Jerusalem, [he would] bring the stations back to each church.”

He wanted people to have a physical representation of this important time of year. “So he named the stations and commissioned artists to paint or find symbols of the stations. It became part of the tradition that, at Easter, people would walk and pray while following the stations.”

In a similar way, these symbolic representations of the Stations of the Cross also led to Nativity scenes being made, also at the behest of St Francis.

His desire seems to have been partly fuelled by the times he lived in; until about 1650, there wasn’t a mass printing press. Most people were not literate, so they needed images to tell a faith story and connect them to their faith. Interestingly, in the 21st century, we have come full circle, with images (like those on film and TV) being one of the primary ways we consume and experience stories.

“I found the Stations to be an existential prayer,” explains Douglas of the experience of viewing the variety of artworks exhibited. “Someone came to me after the first exhibition at St Ives Uniting Church and said to me, ‘I was looking for a deep and rich experience of Easter and I have had it, and this seemed to speak into something for me.’”

I’m not religious, but…

“I’m interested in both how we engage people within the church community, but also how we engage people outside the church community,” explains Douglas. “I think theologians are more worried about dogma than the life of faith. Stories only stay alive from one generation to another if they are true. I believe the Stations of the Cross, or the journey to the cross, is true for everybody. As I walk around the exhibition of the stations with people and talk about the artwork, I am staggered that everybody finds identification points with particular stations.”

“It’s really hard to say to someone in the community, ‘Come to church with me,’” says Douglas. “And if you say ‘Come to this exhibition with me,’ you can walk around and talk openly about life and how it relates to what they are viewing.”

“‘I’m not religious but,’ is a common phrase in society” says Douglas. “But the thing about this exhibition is that it actually asks religious questions. I think every human being is addressed by religious questions. Secular media review films like the recent Martin Scorsese film Silence, because it asks religious questions. The idea of substitutionary atonement [the idea that Jesus died for us or instead of us] is a foreign concept to people in the 21st century.

“In the 19th and 20th centuries, we had plagues and world wars and many people died ‘out of place’. In this century, people seem to be able to turn their backs on the notion of ‘out of place’ death and say that they no longer believe in what Christ achieved for us and say they are not religious.”

Douglas even approaches artists who are professed atheists to reflect on the life of Christ for the stations. He believes everyone has the capacity to reflect on these questions for themselves; this is what makes the exhibition so unique. In some way, it can help those who have never reflected about how the story of Christ affects them, to consider just that.

“I am delighted that over time artists have actually wanted to ask those questions,” says Douglas. “And they are making a significant contribution. What I find as a person within the church, is that they continually bring me fresh readings of the story, of things that I didn’t know.”

Walk and talk of Jesus

If Douglas has an objective for the exhibition, it is to start conversations based on the artworks and the artists who contribute to it. As an Easter reflection of the way the Christ story can shed contemporary light in an age where the meaning of this incredible event is slowly leaching out of societal thinking, the Stations of the Cross exhibition is some sort of “existential prayer”. By creatively engaging with the iconic points in Christ’s journey to the cross and his resurrection, the exhibition can help people symbolically take part in that journey. As such, it is a powerful reminder of the relevance of the message of Christ.

“We take these stories of Jesus walking the road to the cross, to his death and beyond his death because, importantly, we include the resurrection station,” says Douglas. ”We asked Shirley Purdie, who is an Aboriginal woman from the Warnum community, to do Station 16. Shirley had won the Blake Religious Prize in 2007 for her work titled Stations of the Cross.

“Station 16 became known as Jesus Comes to Warnum Today, so this station has been introduced to demonstrate how Jesus is present in the world today.

“If we can set up an environment where people walk the walk of Jesus and have a conversation about what that means in their life, that’s what I’m about.”