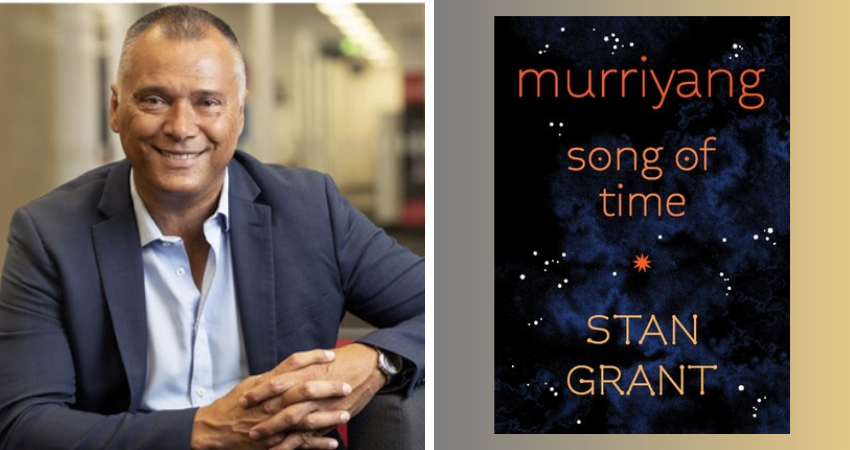

Review: Murriyang Song of Time, Stan Grant, S&S Bundyi

It is not hyperbolic to say that Stan Grant’s latest book is a response to trauma, not only to the rejection of the Voice proposal, but also to childhood marginalisation, racism, a toxic high-profile media, and the failure of his own journalistic crusades. It’s also a deeply spiritual and Christian book, documenting Grant’s search for meaning and love within the church tradition in which he grew up, as he works through lament, forgiveness and the recognition of grace.

If one was being unkind, one might say the book is a mess – all over the place, as he ranges from telling his father’s story to channelling Christian mystics to contemplating the mysteries of quantum physics, letting the narrative meander. But as well as being like yarning or simply an outburst of honest grief, it feels like a search, a little like Jesus’ parable of the man searching for the pearl of great price, looking twice in all the places one might find beauty.

The book is partly about the conundrum of time and how it has been thought of from Augustine to the quantum physicists. Contemporary culture is obsessed with time, yet Grant describes time as a thief, robbing us of all but the present, a notion not generally found in Indigenous culture, which offers a different approach to time.

In modern culture we reside in a fast-paced present, but are, generally, rootless, out of touch with the intricacies of place. Indigenous culture, on the other hand, he says, is not timeless but differently oriented, directly in touch with the past and measuring identity through connection to place, unlike the Western idea of identifying ourselves by our position in history, admittedly a legacy of Christianity. In dealing with his burnout and grief, Grant is working through distancing himself from the modern present, embracing a wider timeframe and embracing Country.

Another aspect of modernity is the prioritisation of the rational and scientific over spirituality, which is seen as superstition, a legacy of the Enlightenment. Grant suggests that many people are open to spirituality, but it is denigrated in the public sphere. He identifies the citizen of modern society as ‘homo solitudo’, with access to material goods but unhappy, shallow, bombarded by entertainment but not meaning, self-regarding, lacking empathy. Building on John Milbank and others, Grant argues that Western liberal society is not in crisis but is the crisis.

We are now living in the wreckage of the Enlightenment, Grant suggests, where success is measured by acquisition, not love, argument is prioritised over conciliation, a deluge of words over listening. For Grant, his is a book about how to leave the world of media, of professional friction and noise. Being a book about responding to the Voice proposal, it is about communication and language, communication with the divine, speaking across time, communication without words—exploring Indigenous language, identity, and how music connects the head and heart.

But it is also a book about silence, in which there is space for listening. At one point he says that sitting in silence is the only real option when Australia has said no to the Voice, when the nation, he says, never really listened properly to the Uluru Statement, encouraged in meanness by politicians. Like Job, Grant sits in the ashes of thwarted generosity, where reason and fine words fail.

Where to next? One aspect of the book that may confound less churched readers is his insistence on the need for God (beyond merely an apologia for his own faith). ‘Writing about God invites scepticism [in Western society],’ he says, ‘Yet write about God I must.’ He addresses those who might wonder how an Indigenous man can embrace the God of the coloniser, arguing that the God of Christendom is not the God of Christianity, and that Australian Indigenous people knew God before the arrival of the colonists. In the concept of murriyang, from which his book takes its title, meaning between heaven and earth, is an indication that Indigenous culture was in touch with an expansive notion of God and the human place in the cosmos. Beyond Panentheism, Grant insists that Aboriginal people knew the Christian God, and he identifies with Jesus as a dark-skinned man in an occupied land.

Grant dialogues with the likes of Christian mystic Simone Weil, who thought deeply about how God is with the sufferer and in the suffering. At the same time, God is love, and Grant is in the process of turning from trauma to wherever the light of God’s love can be glimpsed, within the rubble and wounds. He glimpses God in everything from his mother’s mystical experiences to the music of John Coltrane to the love of friends finding beauty amongst the horrors of war. And in the love of his father, who lives a world away from the politics, referendums and media chatter. If there’s a takeaway here more than Grant’s own therapy, it’s that, for the disillusioned, hope and beauty and meaning are quietly waiting to emerge through the cracks of our lives, beyond the distractions of contemporary society.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.