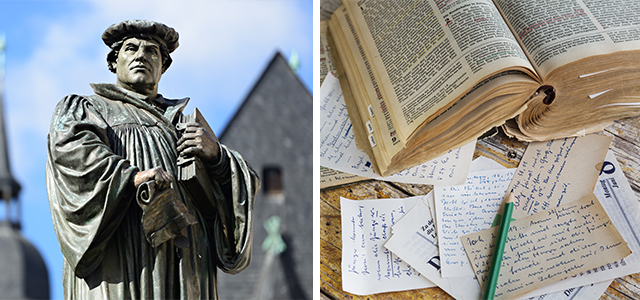

In 1517, priest and theologian Martin Luther nailed his ‘95 Theses’ to the door of a church in Wittenberg, Germany. The rest, as they say, is history. Luther’s call for debate on the Christian faith would lead to the Reformation that shook the very core of European thinking on religion, politics and culture.

To commemorate the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, Dr Janice McRandal explores the Uniting Church after 40 years and the Reformation after half a millennium.

“It strikes me that this may be one of the differences between youth and age: when we are young, we invent different futures for ourselves; when we are old, we invent different pasts for others.”

The Sense of an Ending, Julian Barnes

Infatuated as he is with time, the English novelist Julian Barnes frequently reflects on memory, history, narrative, and meaning-making. He draws attention to the muddled truths which spill out in the accounts of ourselves and our histories.

I am mindful of this inevitable scrambling as we mark time together as the broad Christian church: 500 years since the 95 Theses and 40 years since the formation of the Uniting Church in Australia.

We are registering the passage of time, counting significant moments of the continuous but always uncertain march of history. Just what have we gathered to do, though? Invent a future? Invent a past? Perhaps both at once?

The Uniting Church is a relatively young ecclesiological experiment, a repetition of the past into an unknowable but hopeful future, an inheritance of the past that won’t let the past remain simply what it was.

At its best, the Uniting Church is discovering itself ever anew, not because it shuns the past, but because it invites the past into a pilgrim cadence, a way of walking, or perhaps dancing, through time, in response to the call of the pilgrim Jesus who moves in history in “his own strange way”.

And so gathering to think about the time of the Uniting Church, we cannot help but think theologically about time itself. About the sense of time we have inherited from the past, and also about the sense of time we are discovering, or creating, or inventing, together.

“The Uniting Church is discovering itself ever anew, not because it shuns the past, but because it invites the past into a pilgrim cadence.”

It is in Luther that we find the emergence, or at least reinvigoration, of the category of expectancy in Christian thinking: the idea that faith orients itself to what is coming rather than to what is discernibly present. Faith does not see what is coming; it cannot anticipate or calculate what is coming. But it holds itself open to the future with a trust that feels out its way in the dark.

“Justification by faith alone” is one of the most famous slogans to emerge from Luther’s famous 95 Theses, and it carries a logic of temporality. At present, we are sinners without any hope of securing our own righteousness. Any future extrapolated from this present is a future in which we remain sinners. What then justifies a hopeful movement through time?

Faith alone does. That is, faith entrusts itself to a future in which we will always have been the beloved children of God, even when we were sinners. There is no rational ground for this trust. It does not grow out of any “natural order of things”. It calls for a naked readiness to be embraced by divine mercy despite everything. For those who live with such readiness, a radical freedom is born, the freedom to love and serve without the anxiety of securing a future we can see, or that we have earned. Luther puts such expectancy — or faith — to “work” against the kind of metaphysical gestures that attempt to construe the life of faith as a process of accumulated merit. Put in terms of temporality, Luther refuses any future extrapolated from any present state of things (or, of the potentiality of those things).

This is not without problematic applications, not least of which is Luther’s conception of the two kingdoms — or two temporalities — which fuelled his opposition to the peasant revolts which emerged during his lifetime. Luther found in such revolts a problematic overturning of the law that must, he thought, structure political and economic life in the present evil age. He was unable to hear the Gospel in the peasants’ demands for a new world. But despite its problematic applications, we can say that the Reformation sees a reframing of time along lines of eschatology (the theological study of the final events of history and the ultimate destination for humans). The movement of faith is timed or rhythmed by expectancy. Faith moves by waiting for what it cannot secure or construct and for what it will not possess.

Faith works by trusting a future that arrives only as a gift.

For the Uniting Church in Australia, from the establishment of the Joint Commission on Church Union and right through to the present day, a clear eschatological lens has shaped the Church’s sense of time.

I often think of this as a kind of mystical and apophatic* eschatology, an eschatology more engaged with the promise of a new, extraordinary reality of divine union rather than with the anticipation of a content-filled future. Our language in the Basis of Union marks such a posture: “The Church lives between the time of Christ’s death and resurrection and the final consummation of all things which Christ will bring; the Church is a pilgrim people, always on the way towards a promised goal; here the Church does not have a continuing city but seeks one to come.” (Basis of Union, Paragraph 3)

It is a theology of eschatological patience that shapes the Uniting Church’s sense of calling as a pilgrim people, a theology that waits, a theology that suffers its own incompletion. Such incompletion and the apophatic patience that nourishes it is embodied in a commitment to abide together in the most patient ways.

This patience is not an abstracted virtue but eminently practical, written into all our forms of governance, even down to our manual for meetings. Whereas worldly eyes might look upon such patience as a form of foolishness, the eyes of faith see the practice of such patience as the dance of a strange, difficult joy.

The joy of gathering around what cannot be possessed or lodged in us, the joy of a gift that does not become a possession.

And yet, as we’ve moved toward marking and celebrating our 40 years together, time has come to be marked by urgency in the Uniting Church: a sense of confusion about mission. We seem to have replaced our theology of patience with an ideology of panic.

“It has been 40 years so shouldn’t we have some momentum by now?”

I am not sure that 40 years should mean what it seems to mean to many in the Uniting Church, because for us it has always been eschatology that holds all things together. What would it mean for the Church to resist the temptation of impatience, of knowing itself and a world too quickly?

Perhaps we need to think of eschatology as an art: the art of patience, a patient art. As Julian Barnes suggests in his most recent novel, “Art is the whisper of history, heard above the noise of time.”

This is part of a series exploring the 500th anniversary of the Reformation and the Uniting Church in Australia. This article was first printed in Queensland Synod’s Journey and subsequent parts of this series are available at: journeyonline.com.au/reformation

*Apophatic theology—also known as negative theology—is a theology that attempts to describe God by negation, to speak of God only in absolutely certain terms and to avoid what may not be said. In Orthodox Christianity, apophatic theology is based on the assumption that God’s essence is unknowable or ineffable and on the recognition of the inadequacy of human language to describe God. The apophatic tradition in Orthodoxy is often balanced with cataphatic theology—or positive theology—and belief in the incarnation, through which God has revealed himself in the person of Jesus Christ.