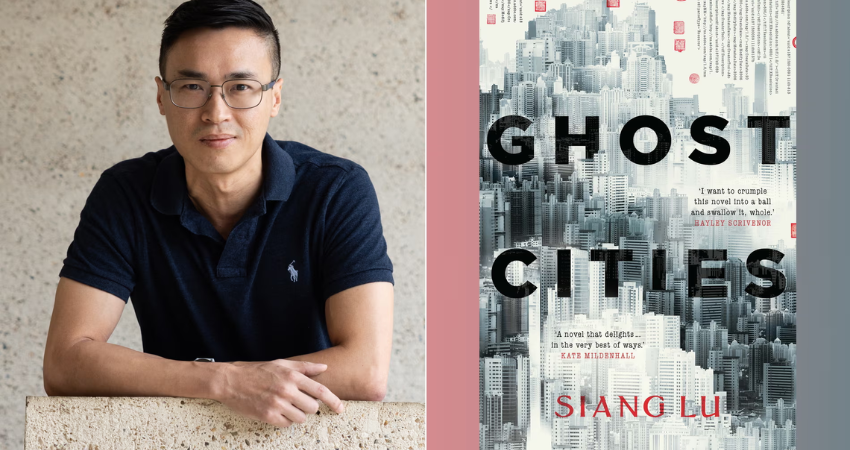

Review: Ghost Cities, Siang Lu, Uni of Queensland Press

A recent phenomenon in China is the so-called ghost cities, built largely as investments for the spreading middle class but unpopulated, leaving forests of empty skyscrapers (though some of these cities are slowly being populated now, a decade after the economic slowdown that caused them). Partly, these cities are uncanny because of a reversal of logic, or an illogic – normally demand for housing drives building; an unpopulated city makes no sense.

As well as one ghost city becoming the setting for Siang Lu’s terribly clever novel, he plays with logical absurdities or paradoxes to comical effect. In ancient China a royal taster is killed by a mob and replaced by his infant son, whose food must be liquified. The emperor asks for stories about himself then kills the storytellers, he commissions artworks which he then decrees must be destroyed to show the artists who’s boss.

In a parallel, contemporary story – a young man, Xiang, is fired from his job as a translator in Sydney because, although he is of Chinese descent, he doesn’t know Chinese and has been using an online translation program. He becomes an internet sensation as #BadChinese, which then prompts a visiting Chinese film director to think he can piggyback on Xiang’s fame, and the director asks Xiang to return with him to China to the ghost city which is the set of his forthcoming movie, and which is he populating with numerous extras. Xiang falls for the director’s translator, who is somewhat redundant, as the director speaks English anyway but feels compelled to play the part of the ‘foreign’ artist.

As the book progresses, we begin to see parallels between the emperor, who is creating a fantasy world, and the Director, who is increasingly referred to with a capital ‘D’ and the definite article, and who is becoming more like a dictator. The name of his film company is Daedalic Productions, which should be a red flag for Xiang, as Daedalus, in Greek mythology, as well as being the father of Icarus, was the creator of the labyrinth.

While in the parallel tale, and like something out of Borges’ fiction, the emperor has a labyrinth made so he can banish an unfaithful concubine there, the ghost city is a labyrinth of sorts – extras living there can’t leave, are controlled, and the line between real life and fiction is blurred: they go about all manner of business at the request of the Director and his Department of Verisimilitude and are told to act normal in case a film crew arrives. Increasingly the film set becomes a real city, and also a kind of prison, and movies seem beside the point. Critics of the Director are banished to labour in factories.

There is a revelling in postmodern theory here. The Director is criticised for making bad movies, but the Director protests that the critics don’t understand he is making a ‘simulation’ of bad movies. The situation is a delightful feast of Baudrillardian absurdities, where the simulacrum becomes the real thing. The movie becomes real life. ‘It’s real and it’s not,’ says Xiang of the city. In the tale set in ancient China, an artist inside an apparent automaton beats the emperor at chess. The paranoid emperor hires doubles of himself, but then his doppelgangers take turns in ruling and making ridiculous pronouncements, and no-one can judge who is the real emperor. But with a history of usurpations, which emperor is ‘real’ anyway?

Amusingly, the name of the ghost city is Port Man Tou, and a portmanteau is a word made from parts of other words – a hybrid thing, and the city is a strange hybrid of the real and pretend, just as a ghost city is a strange mix of dense and empty. Surely all this is a commentary on contemporary China itself, where communism is meant to free the masses, but they work in factories just like in the worst capitalist cities. And more than this, there is the reality within China and the public-facing, global façade, with constant surveillance to ensure citizens act out unity. As the surveillance becomes more high-tech, citizens have to act as if a camera could be on them at any minute. In Orwellian fashion, you have to act authentic or you’ll be found out.

Not that this is exclusive to China – in all countries there is a push to control the national narrative, a front of unity that often overshadows disharmony and is intolerant of dissent – just look at the way contemporary Australia pretends to value the richness of our Indigenous past while simultaneously veiling the violent disruptions of that past.

Xiang is fond of Paradise Lost, Milton’s epic poem, which, he explains to his love interest, inadvertently mentions two Chinas. Xiang asks if maybe there are indeed two Chinas, a real and a mythic, and he goes on to mention how there is real Chinese food and tourist Chinese food, advertised as authentic but anything but, and which real Chinese don’t eat. (They chuckle over the concept of lemon chicken.)

But Xiang too is playing roles – as he begins to learn Chinese, #BadChinese is a role he is playing rather than the actuality, as he is no longer humorously ignorant of Chinese, and the character is no longer relevant, just as the term ‘ghost city’, and even the concept of it being a film set, is no longer relevant for Port Man Tou. Conversely, as romance blossoms, he muses, are we, within romantic relationships, not performing our best selves, trying to ‘be ourselves’ while simultaneously putting on a show? Performing authenticity?

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.