Review: What an Owl Knows, Jennifer Ackerman, Scribe

Growing up on a farm in rural southern Australia, we would hear owls at night – we called them ‘Mopokes’; that species is otherwise known as the Boobook, named after its two-note calls. Our owls lived in the barn and sheds, but I don’t recall seeing one, which says something about the nature of owls. Along with other nocturnal creatures, they inhabited another world to ours.

Owls can be found in the 30,000-year-old cave art in Chauvet Cave. They are associated with wisdom, of course, from ancient Greece to India. The Winnie the Pooh stories play with this by making the owl character a pompous know-it-all who is often off-the-mark. With their binocular faces there is something more human about owls than other birds, but then the other side is that they are creatures of the dark that can sneak up on you (a characteristic enabled by specially adapted sound-dampening feathers on their wings). Their nocturnal habits and eerie calls mean they have been associated with witches and demons in folklore.

In American Indian culture they are seen as both good and bad, even as returning spirits of the dead, depending on the context. The Bible forbids the eating of owls, along with other birds of prey. In the Books of Job and Jeremiah owls are linked to isolation and ruination, presumably because of their calls during the night and their habit of roosting in isolated locations.

Hearing the calls of owls while ill has been widely thought of as an omen of imminent death. Killing owls, unfortunately, has been thought of as a remedy for the bad luck brought about by their presence. Suspicion, even fear, of owls continues in areas such as Africa and Eastern Europe. On the other hand, eating owl eggs in some areas is thought to improve the eyesight, and, more accurately, one owl can kill thousands of vermin – mice, rats – in a year, meaning they should be thought of as friends of farmers.

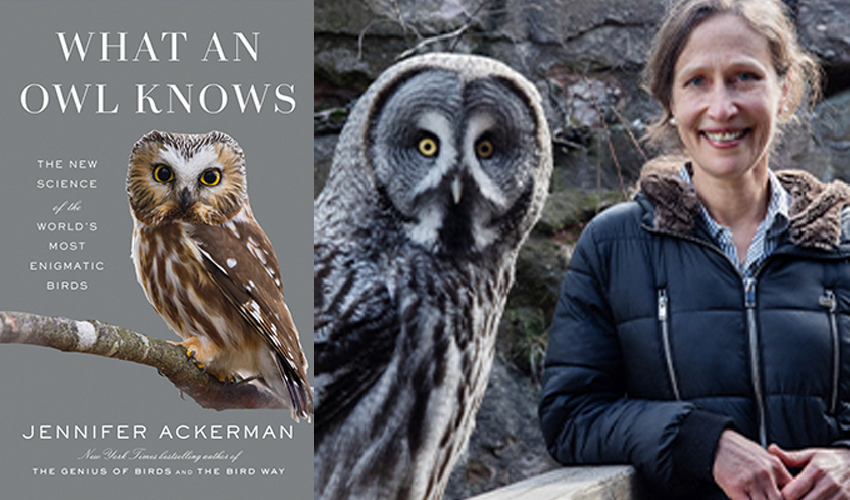

Being largely nocturnal, they have an air of mystery, which scientists are eager to overcome, especially to redress their declining numbers. Jennifer Ackerman, who has previously written much about birds, travels with owl experts and lovers who are studying and saving owls. Her book is as much a story of the people who are obsessed with, and want to save, owls. But because of their nocturnal, wily and stealthy behaviour, owls are difficult to study. Small American saw-whet owls were thought to be endangered until they were properly studied and were found to be plentiful.

Even so, they are widespread, from the tropics to the arctic, from mountains to grasslands. Some are quite specialised, like burrowing owls. Others are generalists, and adaptive, preying on insects to rodents to other birds, even venomous spiders. America’s Great Horned Owl can prey on ducks and cats. In Australia, owls eat brush-tailed possums, which are, as she says, the size of a cat – and they will eat one a day! And yet, despite being powerful predators, they don’t seem likely candidates for a footy team to be named after them.

An owl’s whole facial disk is like an ear, so they can hunt purely by the sound of their prey (which might include, remarkably, a mouse rustling under a pile of leaves). Like an eye, they can adjust the disk to let in more sound. Some owls have asymmetric ear positioning that helps even more with pinpointing the origins of sounds. Working in tandem with this is the makeup of their wing feathers. They have more than other birds, and are not silent in flight, but the feathers create sounds at lower frequencies, resulting from fine, velvety feathers that calm turbulence over the wings.

They captivate researchers with their cleverness. Ackerman witnessed a female burrowing owl digging under a trap at the entrance to a burrow to rescue her young. Rescuers grow fond of them, but they have distinctive personalities and judge some humans as friends, some as enemies. Picasso had a famously bad-tempered pet owl. (His art often featured owls.) Ackerman warns that, despite an upturn in interest due to the success of Harry Potter, owls don’t make great pets – they have sharp talons, smell (due to their diet of raw meat) and can be frightened by humans. On the other hand, because we look somewhat like them, and they like us, rescued birds can sometimes ‘imprint’, thinking they are human, and then fail at being re-introduced to the wild.

Despite being out of sight, they do inhabit our world, and suffer the consequences of our ubiquity. They are threatened by cars at night, which can hit them as they gather roadkill or attack prey on the roads. Lead from ammunition fragments in dead animals can give them lead poisoning, and they can be killed by feral animals. Rat poison, which the owls ingest from the dead rats, builds up quickly in owls and is an increasing cause of owl deaths. (Ackerman suggests that we should be avoiding rat poison and using traps instead.)

Habitat loss is another factor. This inadvertent killing of owls by humans can be added to their deliberate killing, which is being combatted around the world by education, which includes, in Africa, programs where school children learn about and draw owls, and a town in Eastern Europe where hundreds of owls roost in an inner-city park and where there is now an annual ‘owl month’, a turn-around from previous malevolent superstitions directed at them.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.