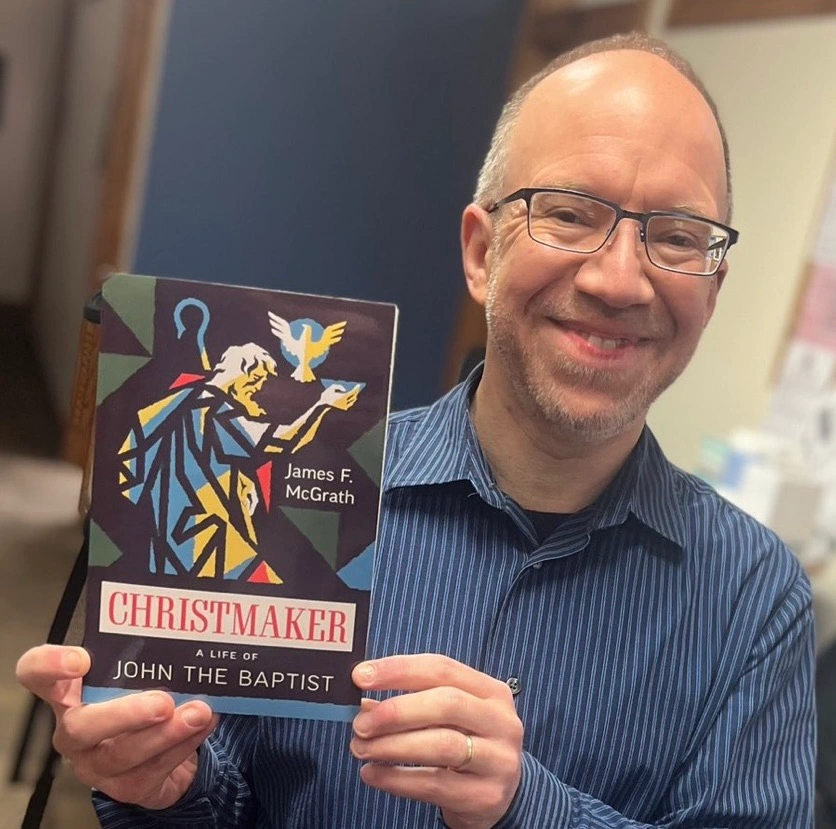

Elizabeth and I recently had the opportunity to attend a lecture at Macquarie University given by our friend and colleague, Prof. James F. McGrath of Butler University, Indiana, who is on a short visit downunder at the moment. James has recently completed two books on John the Baptist, and as part of his visit he is speaking about some of the research involved in producing those books. The first is Christmaker: A Life of John the Baptist (Eerdmans, 2024); the second is John of History, Baptist of Faith: The Quest for the Historical Baptizer(Eerdmans, 2024).

His other personal and professional interest is in the intersection of religious studies and science fiction—he has written other works in relation to this area of interest: Time and Relative Dimensions in Faith(Dayton, Longman and Todd, 2013) and Theology and Science Fiction(Cascade, 2016). James is also speaking tonight at Sci-Fi Church in northern Sydney.

Elizabeth and I met James in 1997, when we were all a part of the research community in the Theology Department at Durham University in the UK. Both James and Elizabeth were undertaking postgraduate research under the supervision of the late Prof. James D.G. Dunn—James, into the Christology of John’s Gospel, and Elizabeth, into mission in the Gospel of Matthew.

The two books that McGrath has written complement each other. Christmaker is unapologetically “popular”, in that is was written for a generalist audience. I can confirm that it is easy to read as it invites us along the journey of discovery that McGrath himself has taken. The second book (a clever riff off the oft-heard statement about Jesus, “the Jesus of history, the Christ of faith”) promises to take us deep into the scholarly explorations of the ancient texts that provide the foundation for Christmaker. In his recent lecture at Macquarie University, James McGrath has provided a glimpse of those scholarly discussions in his typical engaging style.

The small book Christmaker (just 172 pages) opens with typical McGrath-esque snappy commentary: “everybody thinks they know John the Baptist; he has good name recognition”, and yet, “I bet most readers of this book would know him the way they know a homeless man they pass on their way to work each day … [with] an astonishing lack of detail, little apart from vague impressions” (p.1).

The book proceeds to explore “the splash John made” (pp.3–8) and then to set out how a reconstruction of the life of John will be built, using both familiar and less familiar sources. The best-known sources come from Hebrew Scripture—the infancy narratives of 1 Samuel 1—2 and Judges 13—and the New Testament—the conception and birth of John in Luke 1; the Gospel accounts of the baptising activity and preaching/witnessing of the adult John, and the Synoptic accounts of his death. The other sources he uses, barely known outside a small academic circle, are the Infancy Gospel of James from within second century Christianity, and the Mandaean Book of John, from the traditions of another living religion, Mandaeism.

There is, obviously, solid and groundbreaking scholarly work lying beneath the surface of this accessible “fresh look at the life of John the Baptist”. One element of this is that McGrath has co-authored the only English translation of the Mandaean Book of John, published in a critical edition (de Gruyter, 2019) which takes the readers on a wondrous journey into the poetry and imagery of this 7th century Aramaic text.

Since late antiquity, the Mandaeans have followed the baptismal practice of John and have revered him as the key figure in their religion. Communities of Mandaeans are to be found in many places around the world today, still practising their faith. One significant characteristic of McGrath’s work is that he has connected with, and interacted with, Mandaean communities in a number of countries.

By discussing his views with them, he has ensured that he is best understanding (from the vantage of an “outsider” to the religion) how John is today understood within that faith tradition. Indeed, there were a number of Mandaeans present at the lecture that Elizabeth and I attended, and they offered helpful insights into the thesis that McGrath was proposing.

Another contribution to the fine scholarly work that is evident in this book is the careful critical reading of the Infancy Gospel of James, a second century Christian text replete with miracles and extravagant tales relating to the birth of Jesus (chs. 1–20) and the death of Zecharias, father of John the Baptist (chs. 22–24).

By reading these two unfamiliar texts alongside the biblical passages already noted, McGrath is able to posit quite a lot about the quite overshadowed—and largely misunderstood—figure of John the Baptist. He wasn’t an unkempt and unruly figure, wandering the desert, angrily denouncing his fellow-Jews, for one; rather, he travelled the rural areas, proclaiming his vision for Israel. McGrath has visited many of the sites traditionally associated with John in person—beyond the all-too-predictable River Jordan spot where John’s baptisms were said to have taken place. So this adds another dimension to his discussion of the traditions.

John was not, as might have been expected of the son of a priest, devoted to service in the temple; rather, he was “an antiestablishment rebel and activist”, challenging the hegemony of the Temple through the practice of baptism, for which he is best-known. Such baptism “invited people to have a mystical spiritual experience of rebirth”—leading, eventually, to a Gnostic-type movement (Mandaeism) which embraced his practice as the key to religious fulfilment.

John did, indeed, look to the coming of “one who is to come”, to rectify the classism of ancient Israelite society—although it is not necessarily so clear-cut that John himself actually envisaged any particular one of his followers (let alone the man from Nazareth, Jesus) as the one to fill that role.

And, in a surpassing twist, it may well have been the overenthusiastic action of this particular disciple, Jesus of Nazareth, who sought physically to overturn the practices of the Temple in his famous “Temple tantrum” (a catchy phrase that McGrath has used in conversation with me). So it was John’s stimulus of Jesus which provoked controversy about his movement through this act, leading to the arrest of John and his eventual death. That Jesus might have borne primary responsibility for the death of John is a twist, indeed!

So, what can we take from this fascinating tour through ancient texts and modern religious practices? That Christianity started within a very specific social and religious context—the Baptist movement—and not just within an undifferentiated amorphous mass of “Judaism of the time”. Jesus, as a disciple of John, adopted his teachings, his practices, his vision. The introduction that Luke provides to his Gospel, focussing on Zechariah, Elizabeth, and John, needs then to be reconsidered in this light.

Second, that piecing together a life of John the Baptist can and should be done by judiciously critical use of the later Mandaean sources. Scholars have learnt, in the last half-century, to utilise material from rabbinic writings in Mishnah, Midrash, and Talmud—works from late antiquity—with appropriate care and critical acumen, to inform our discussions of the foundational documents of Christianity (especially the Gospels). In similar manner, a critical appreciation of the Mandaean Book of John offers a range of applicable insights.

Third, scholars have become aware of “editorial fatigue” in their treatment of various ancient texts. This refers to the practice of including source material without paying careful attention to the need to adapt and contextualise it for the later writing in which it is used. Evidence for this “editorial fatigue” can be found in works by historians, evangelists, and apologists alike. McGrath cites instances in the Infancy Gospel of James which throw light on the figure of John the Baptist—especially the jagged change in ch.22 from a story about Jesus, to a story about John.

On this basis, he proposes that the author of this second century Gospel was using an existing account of the infancy of John and adapting it as a story about the origins of Jesus. An editorial lapse (forgetting to change the names of mother and child!) provides the key to unlocking this reading. We may well, then, have access to an early tradition about John, separate from the apologetic way that he is portrayed in the New Testament Gospels (where he is portrayed as “second-fiddle” to Jesus).

So a readily-accessible “life of John the Baptist” (set out with clarity in Christmaker) becomes possible, by tracing and examining the interlocking and overlapping threads across three religious traditions—Judaism, Christianity, and Mandaeism—through the various source documents already noted. What results is a creative, insightful, and groundbreaking book. I recommend it as worth purchasing and reading.

Rev. Dr John Squires is the Editor of With Love to the World. This review originally appeared on his blog, An Informed Faith.