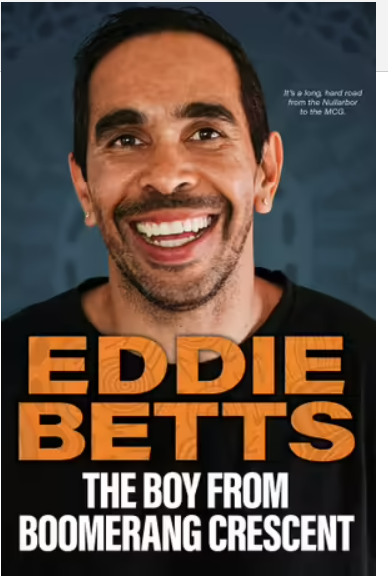

Review: The Boy from Boomerang Crescent by Eddie Betts

Let’s get the controversy out of the way first:

In 2018 the Adelaide Crows football team, after a thrashing by Richmond in the 2017 Grand Final, organised an unorthodox training camp that ended up being notorious. Run by outsider, supposed leadership and motivational experts, the camp was a kind of abusive, quasi-military, traumatic experience. The players flew to the Gold Coast, were then blindfolded and put on a bus, on which they were berated for the Grand Final loss. At the camp they were subjected to weird, cruel, and aggressive ceremonies, some of which imitated Indigenous ceremonies, making Indigenous players extremely uncomfortable. The aggro camp leaders yelled abuse, made team members abuse other team members, often utilising private and intimate information obtained in ‘counselling’ sessions beforehand.

When Eddie Betts, then a star Crows player, and his wife later questioned what had gone on at the camp, Betts was removed from the club’s leadership group.

Distressing as the camp was for all players, it was more so for Indigenous players, because sensitive Indigenous words and ceremonies had been used inappropriately and disrespectfully, and it said something wider about attitudes to Indigenous people, yet another incident where trust was betrayed, and culture stolen.

Indigenous players are over-represented in AFL teams yet continue to be treated badly – whether we think of Adam Goodes being forced out of the game, or the racist culture at Collingwood, or Betts’s experiences. An unusually good-natured and respected guy, Betts describes the sense of unsettling difference he felt, on and off the field.

There are warm stories in Betts’s book, and also some unremarkable ones, and the usual cliches about the ‘boys’ on the team that you expect from a sports memoir. The phrasing is simple, but it’s significant that the book exists at all, as Betts was illiterate when starting his playing career with Carlton. This is not unrelated to his being Indigenous.

Betts grew up in Kalgoorlie. His grandfather died on the floor of a prison cell. (Betts recounts this in the midst of talking about other, happier, childhood memories.) It’s indicative of attitudes of the time that his grandfather probably had some other illness, but police assumed he was drunk.

Betts points out that family for him and other Indigenous people usually meant, and means, a wide family. Biological cousins were more like brothers and various aunties, not just mothers, did the job of mothering. The community respected traditions and tried to uphold them as best as they could, but they were also traumatised. And any escalating differences within the community had to be worked out without the police – they would only make things worse. Betts notes that he was picked up by the police for minor infringements. That seemed to be the lot for Aboriginal kids, while white kids got away with the same things.

Football was a ‘language’ he understood deeply. He says he was never much of a fan – watching football only took him away from being outside and actually playing it. His talent recognised, he was eventually picked up as a teen by the Calder Cannons in Melbourne’s north. Thrilling as this was, he missed family, and he describes the ‘shame’ he felt catching the train after training, while his teammates would be picked up by their parents. (Betts was undoubtedly shy, and bottled his worries, but one wonders why no-one at the club, or amongst the parents, noticed all this.) Players from the country, thrown into the spotlight of big city football, can struggle. But this is compounded for some Indigenous players, cut off from family, Mob, freedom, Country. Betts describes the contrast to the city in the off-season – BBQ kangaroo, dampers, sleeping under stars.

‘Footy was the equaliser,’ says Betts. But Betts was more equal than others. He says he always had a sense where the goals were, which meant he could kick miraculous goals. (Set shots from straight-on were harder.) He played basketball as a kid, and aside from his trademark baggy shorts, this seemed to give him an instinct for weaving through traffic, as well as control of the ball – he would tap or bounce it in front of him like a basketballer. In possession of the ball, he would be mesmerising – not ballet-like exactly, but darting and spinning, staying close to the ground, pulling himself through the eye of the needle to get the ball between the big sticks. He won ‘goal of the year’ four times. Taking a mark, he was like a cannonball, gaining height not from his own height, but from springy momentum.

He received racist abuse in old-fashioned letters and on social media. He copped it at grounds from crowds. When he won his second ‘goal of the year’, he won a car. Police pulled him over to hassle him about whether the car was his – with no seeming reason than that he is Aboriginal. He was once arrested outside a nightclub, earning him the media tag ‘Bad Boy Betts’. But ‘Bad Boy Betts’ was a beat-up, and he was probably arrested for the same reason – as well as for being Eddie Betts. This prompted him to keep his head down. But even as was finishing up his AFL career, he held a fear of the police.

As an older player, he mentored younger Indigenous players, which meant much more than just on-field advice. Skill is paramount in football, but it only takes you so far. You also need an environment that doesn’t hold you back because of the colour of your skin, and Betts has been quietly persistent in trying to change culture within and outside the AFL for the better. (He says he doesn’t have all the answers but can at least show from his own experience the corrosive effect of racism.) And while skill might see you lauded in the sports halls of fame, Betts’s story shows that what you give of yourself off the field is more important.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.