Review: This Isn’t Happening: Radiohead’s Kid A and the Beginning of the 21st Century, Steven Hyden, Hachette.

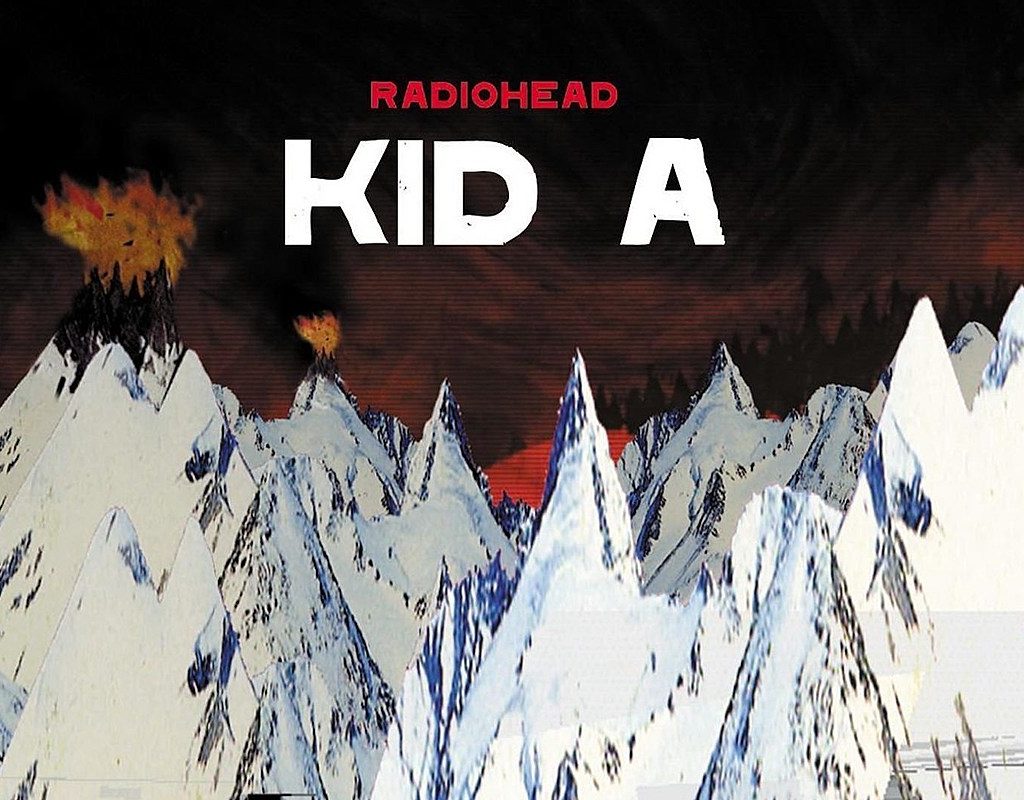

Twenty years ago (in 2000), after the universally lauded album OK Computer, Radiohead did a Sgt Peppers and confounded critics and fans alike with the release of the Frankenstein’s Monster-ish Kid A. It was not the most radical music ever, but it was a radical change for Radiohead, and that’s the point, for the band was sick of being cast as some sort of saviour of rock, and were trying to smash down the walls of the corner they found themselves in.

This turn of the millennium also happened to be a time when the music industry was transitioning to an online world, shaking the foundations of traditional ways of disseminating music, moving from CDs to downloads, and eventually, as Steven Hyden notes, to streaming. In Hyden’s book on Kid A he describes the album’s creation, the controversy, and the band’s career before and after. He also ponders what was said, or implied, by the album’s inarticulateness, about the disjointed times into which it was born – the evolution of the internet, the malfunctioning of politics, growing climate threat.

Kid A is as of its time as those bloated, late 70s prog rock albums with sci-fi artwork. And what was weird then – electronic bloops, processed vocals, jarring elements – the album’s supposed innovations – were already long established in the music of acts such as Aphex Twin, even ambient pioneer Brian Eno. Nowadays, even Taylor Swift’s music has stuttering drums and treated instruments wafting in and out, and skittish beats and manipulated sounds are ubiquitous across TV advertising. And now Kid A is part of the pop/rock canon. There is a certain inevitability about this. Acts that push the envelope are eventually filed under ‘classic’ and/or inducted into a hall of fame of one sort or another. Art that once created scandal becomes beloved, like the Impressionists, jazz, even classical music of the likes of Wagner.

Unsurprisingly, Hyden compares Kid A with U2’s work with Brian Eno, when they came up with Zooropa in 1993. This left-turn reinvention stuff had happened with the Beatles, and way before Kid A, U2 had re-invented themselves with 1990’s Achtung Baby, but Zooropa was U2’s Kid A, borrowing similarly from electronic dance and clanky industrial rock. Like Radiohead U2 cast an ironic eye over consumer culture and the power of corporations. The Edge sang ‘Everything’s just fine’, and just like when Thom Yorke sang ‘Everything’s in its right place’, you knew it most certainly wasn’t. Rather than being explicit about it, Zooropa said something about the times by being all over the place. Ultimately U2 and Radiohead went in different directions. By the end of the 1990s, U2 had (unfortunately) U-turned and gone safe, just as Radiohead made their left-turn and dropped Kid A, and continued to experiment and confound. (Or, more truthfully, just continued to make music they found interesting.)

Hyden’s book is about the big issues of what it means to be in a band, what making music means, about the tension between experimentation and emotional connection. He asks how a band knows when it’s being itself (whatever that might mean) and what a band does when it becomes too famous and is taken too seriously (including by itself). He gets into a few too many what-ifs and admits that it is easy to read into Kid A what might not be there. He is a Radiohead geek who knows possibly too much about them, and also possibly overstates Radiohead’s intergenerational relevance. But he is intrigued at how Radiohead fits into wider schemes.

More widely, he looks at the internet and culture, how the likes of Spotify have commercialised and homogenised things, how rather than being an online community (an oxymoron, I suspect) and a land of liberty, the internet is now a place for groupthink and rampant exploitation, and a place of exhaustion brought on by too much choice.

But the book also conveys Hyden’s wariness about the limits of the power of music. He recognises that music has power, especially for young adults, but also that that power fades somewhat. I think Radiohead is a good example of the fact that despite its power as art, music is not usually ‘subversive’ in a wider sense, despite what egocentric rock stars might think. Kid A was of its time in conveying a sense of foreboding, partly brought on by what was happening in the world, and an interesting piece of art because of that, but it couldn’t do anything more than that. Music won’t save the world. You have to look elsewhere for that.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com