Review: Hospital, Sanya Rushdi, Giramondo

In art and literature it’s easy enough to sensationalise or glamourise mental illness, but Sanya Rushdi offers a more complex understanding of it in her remarkable little novel.

Written and published originally in Bengali, and translated for Sydney’s Giramondo Publishing, the novel is about Rushdi’s experience with psychosis and hospitalisation, in the context of her studying psychology and living in Melbourne with her migrant family. I recently attended a launch of the strongly autobiographical book, and it was said that the novel format allows, counter-intuitively, a level of honesty about her condition, and what are perceived as the right treatments. At the start of the book Rushdi is encouraged to paint for therapy, and just like this, a novel allows for layers of understanding of her subjective experience to be worked up on the pages.

The book is calmly narrated, with periods of psychological and philosophical insight, befitting a student of those disciplines. She shows mental illness is not the opposite of intelligence. Rather, it is a matter of entanglement of the connections between everyday events and meaning. I feel like this is something that many of us encounter, but of course psychosis is a dangerous and heightened experience of it.

In the novel, lucid speech turns, not in tone, but towards a feeling of extracting too much meaning from the everyday flow of life. But where some patients may leap to conclusions, her intuition of deeper meaning that is not there leads her to feel she is missing out. When a nurse takes her to a café, the nurse pays with a $50 note, just like her PhD supervisor had done, and she wonders whether this is coincidence or a connection she is not privy to. At one point she is listening to a song with the Bengali word ‘shabab’ in it, and the patients of the ward she is in keep talking about ‘rhubarb’ (which was in the night’s dessert). She wonders how they know what she was listening to.

Doctors ask if she sees codes in the newspapers, but she wonders if others around her, like her family, are using codes because she cannot quite follow the gist of their conversations. There are stretches when she is lost within herself, oblivious to surroundings. It is hard to weigh things: she complains to a counsellor about coping with the proliferation of technology, but the counsellor says that it’s okay – everyone feels like that.

Some of this has a darkly humorous edge to it. When she is staying at a ‘community house’ she is given a room with the number ‘6’, and she wonders if she will need an exorcism. When her suspicions turn into an episode of paranoia, her family comes to collect her, and when they ask her how she is, she answers, like a punchline, ‘I’m fine’. When she takes a seat on a train, she sits on the right, and then wonders if that will be misconstrued as support for conservative politics.

Passages of scientific explanation, tied to her studies, are all the more powerful because there is a contrast between her not knowing or understanding because the usual links of causality – keys to science – have broken down. At the same time, strict attention to causality – especially in the use of drugs – means a lack of what she thinks of as holistic treatment.

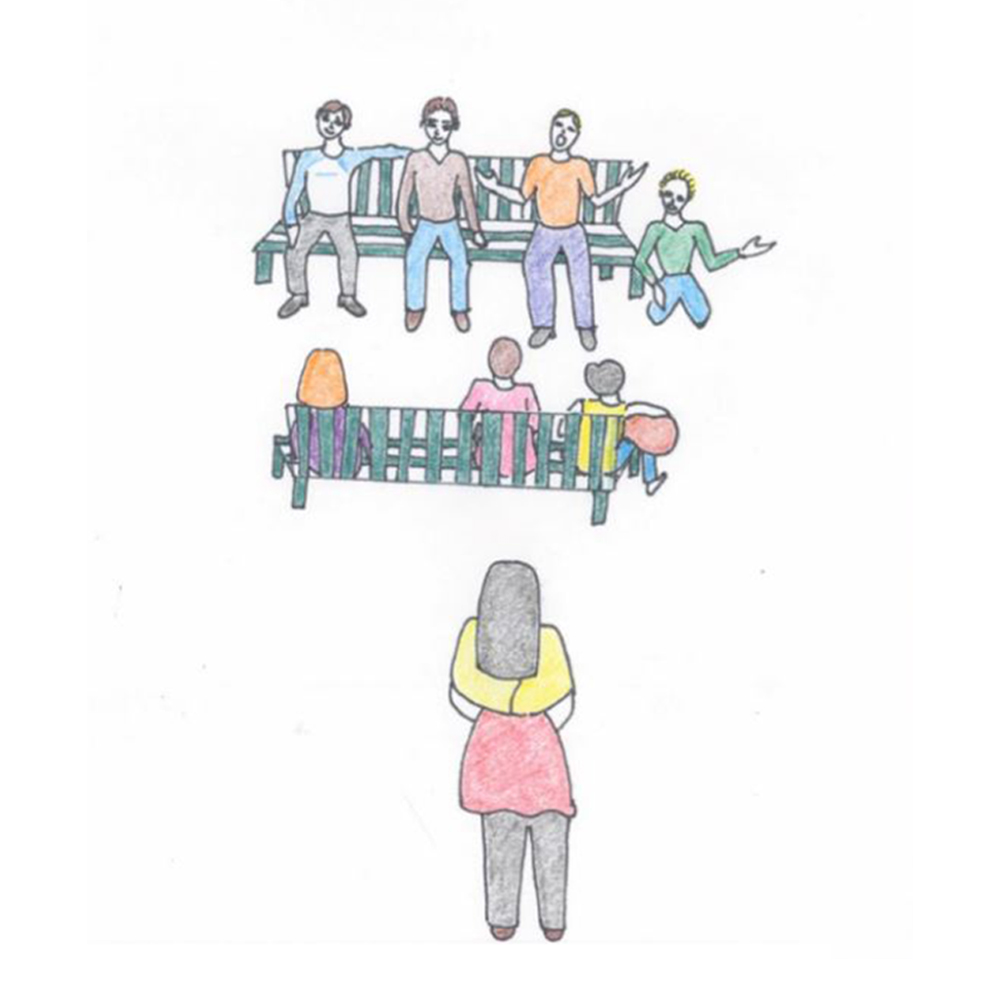

She pushes back on doctors, arguing that medication and traditional counselling are inadequate, and that what is needed is conversation based on connection. She, in turn, is warned against getting too friendly with the ‘boys’. In this, the doctors seem somewhat sneaky, their questions loaded, whereas there is an honesty and generosity amongst the ‘inmates’. But not always: they don’t understand her Muslim avoidance of pork, for example. And because we are within Rushdi’s perspective, we can’t always tell if the doctors are being unreasonable; we simply feel her lack of understanding.

At one point, as she is imposing symbols on the world around her, she says, ‘I need someone who is in possession of both common sense and compassion’. (This is an interesting use of the word ‘possession’, considering its connotations.) This happens when fellow patients are queueing for medicine (drugs), which she sees as a quick fix. She recognises the need for help, but is wary of a strictly physical, chemical treatment, groping instead towards what a more expansive approach might be.

At the event I attended there was talk of the immigrant experience of fragmentation, linked to the shrinking of community that inevitably follows migration. Immigrants can often feel acutely a lack of community connection that gives meaning. This is similar to Rushdi’s experience with mental illness, of being adrift in a sea of language, both disoriented and buffeted. There is a need for migrants to be seen as real people, rather than objects of study and policy, needing relationships, care, understanding, affirmation, empathy.

These are things we all need, but especially so for those people in society who are marginalised for not fitting into society’s norms.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.