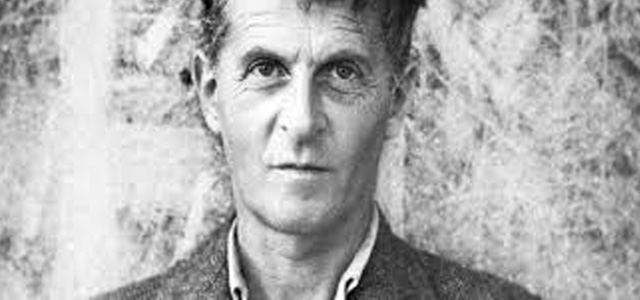

Review: Ludwig Wittgenstein, Miles Hollingworth, Oxford.

Miles Hollingworth’s new biography of philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein is a natural follow-up to his biography of Saint Augustine. This is because Wittgenstein was much taken with the Church Father, and they covered similar themes – the relation of the personal and emotional to truth and logic, human freedom, how the way we talk about things covers deficiencies in our ways of thinking. Both tended to do their own thing, roaming widely in philosophy, unafraid to tackle unorthodox subjects. But reading Hollingworth’s biography of Augustine doesn’t quite prepare the reader for this extraordinary Wittgenstein book, which raises the level of Hollingworth’s writing.

Wittgenstein is rightly famous for his wariness of the modern attention to facts as described by language, the tendency to think facts explain life. This is relevant to our own time when Western society is subservient to the scientific methods of efficiency, utilitarianism and naturalism. Famously, Wittgenstein argued that such language is not just descriptive but prescriptive. Life is often squeezed into the shape of facts, distorting it, and he was concerned about the way a focus on logic lessened the human. In a similar way, Augustine argued that emotions mean human thought is not always logical (which is not necessarily a bad thing).

When it comes to biographies of figures such as Wittgenstein, Hollingworth thinks it is absurd to fit a life into 400 or so pages, into a neat parade of biographical facts, and that much of the essence of a life is lost. (Think, further, of a eulogy and how diminished, unreal and remote the life as described by a eulogy sounds.) This becomes especially paradoxical in the case of a ‘genius’ such as Wittgenstein (which he undoubtedly was), Hollingworth argues, when the traditional biography supposedly sums up in rational, logical fashion how the subject of the biography became a genius, which should really be beyond simple explanation.

So, in order to be true to Wittgenstein’s life – which was not that of a desk-bound academic – he fought in a world war, inherited a fortune, gave it all away, designed aircraft and houses, taught in a remote primary school, lived like a hermit. Hollingworth tries to show how Wittgenstein lived out his philosophy, with all the ambiguity this involves. More than this, Hollingworth tries to, as biographer, show how a biography can wrestle with its subject rather than just put it on a pedestal. As quixotic as it sounds, this biography battles against the deadening effect of biographies, it drags the hidden biographer – the disengaged biographer being a pose, an act – into the light.

It’s a personal style, but it’s not easy. Following the thread is sometimes like hanging on to a crocodile’s tail in order to not be eaten. At times Hollingworth puts his arm around your shoulders and whispers in your ear, at other times he grabs you by the collar. He is conspiratorial, angry, excited, side-tracked. He cajoles, complains. In short, he is emotional, not disengaged. Indeed, he says, what is the point of disengagement? One needs to dive into one’s subject. (Think about it: your best science teacher was passionate about the subject, not cold and clinical.) At one point he exasperatedly says, in effect, look, if you want just the facts, I can do that too, and here they are. And he lays out some of the (extraordinary) facts of Wittgenstein’s life. But this is as much to show what is lacking in this approach to ‘explaining’ Wittgenstein.

Wittgenstein is not an immediately obvious promoter of Christianity, but beyond a reported deathbed reconciliation with the church, Wittgenstein’s subject was often God even when God was not mentioned, says Hollingworth. We can see how his philosophy relates to seeking God, if we think about how, along with Augustine, Wittgenstein argues that if we predetermine that what counts as reality is what is immediately before us, then we are likely to miss some aspects of reality, including God.

More generally, Hollingworth argues that Wittgenstein lived out a calling (in a spiritual sense), in a similar way, we might add, to how the early church showed what it believed by living out, rather than simply arguing for, those beliefs. Indeed, Hollingworth points out that Christianity consists not just of ideals, but rests on action in history. Christ was a real person, and Christianity involves primarily not believing facts but living with passion.

This is perhaps why philosophers, and people in general, are sometimes scared of Christianity. Philosophy, as Hollingworth points out in his book on Augustine, wants to draw a line under things, make definitive statements, stand back and analyse from a comfortable distance and the certainty of logic. The work of God, on the other hand, is ongoing, and he asks for commitment and action in the face of uncertainty. It is not just that Christianity proposes things hard to take as logical, but it asks us to, like Wittgenstein, live out our beliefs to the extreme in the midst of human unpredictability.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com

1 thought on “Wittgenstein and God”

Thank you very much for your account of Wittgenstein and Augustine from Miles Holingsworth ‘s books.