Review: Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma, Claire Dederer

I quite like the music of Ryan Adams, but his music became somewhat tainted a couple of years ago when he was caught up in the so-called cancelling of the careers of men who had sexually harassed women. I still liked the songs, especially the more recent ones, but the listening experience was complicated by the allegations (which turned out eventually to be a mix of the real and the exaggerated).

Claire Dederer’s book is about artists – mainly men – who do wrong, but it’s more about how we react as an audience when our favourite art is stained, as she puts it, by the biographies of the artists themselves.

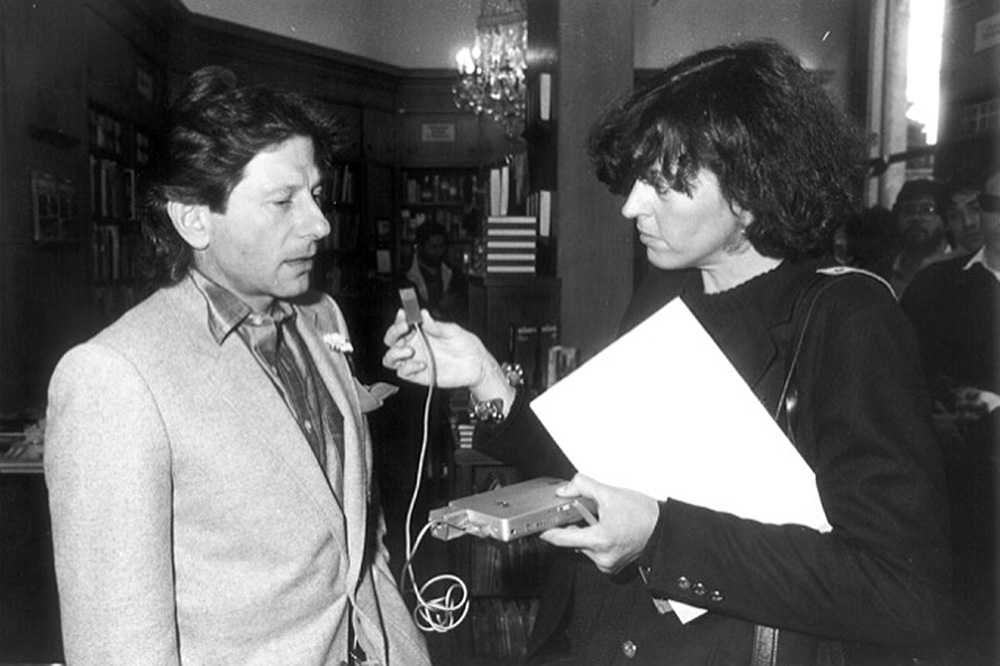

She writes that, obviously, there would be no end to it if she focussed on the bad behaviour of sports stars. Rather, she begins with film director Roman Polanski. While watching Polanski’s films recently she says the thought of his rape of an underage girl ‘hovered there’. While rationality suggested she shouldn’t watch the films, she found herself having conflicted feelings – liking the art but hating the artist.

This experience becomes extra difficult when we feel that although the artist doesn’t know us, we feel they are speaking to us. She feels ‘betrayed’ by Woody Allen because, she says, she identified with him and his (pessimistic) outlook on life, though she also notes that the film Manhattan is somewhat ‘creepy’ because of the main character’s relationship with a much younger woman, which might have been a flag for what would come later.

When discussing Allen, a male friend argued condescendingly that she should separate the art from the artist. George Michael, who, we might add, had his share of troubles but was not monstrous exactly, said essentially the same thing – that an artist’s private life should be just that. But it’s not that simple. Art is inseparable from biography. Think of black blues artists and how their experiences drove their art. (Yet there are degrees. She suggests that it might be easier to listen to [the antisemitic] Wagner than watch The Cosby Show, in the light of Bill Cosby’s crimes.)

She has some really sensible things to say about the bias of our own subjectivity. To assume that we can focus on the aesthetic only is to assume that everyone has the luxury of not being affronted if they choose not to. But if we deal with harassment constantly, we may be unable to let perpetrators off the hook just because the art is good. At the same time, we might not be able to let the good art go, even if we are repulsed by the behaviour of the artist.

As she thinks about biographies and art, Dederer winds her way towards the difficulties of balancing motherhood and career. She examines the lives of women who felt they needed to be selfish to satisfy their art. She notes that men tend to be more monstrous, but she is wary of ‘gender essentialism’. She realises that we all have monstrous tendencies of some degree, and the dilemmas raised by cancel culture are only prominent examples of having to deal with the complexities of human beings. This is what Protestants have thought of as the simultaneity of saint and sinner.

Some men are unrepentant. Woody Allen doesn’t seem to think there is anything creepy about his behaviour. Or maybe he thinks it’s in line with his tortured genius persona. Ryan Adams, on the other hand, has seen something of a revival in his career, with sold-out shows and numerous recordings. He apologised, especially to his ex-wife, and gave up drinking, which was perhaps a necessary blessing resulting from revelations of bad behaviour.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.