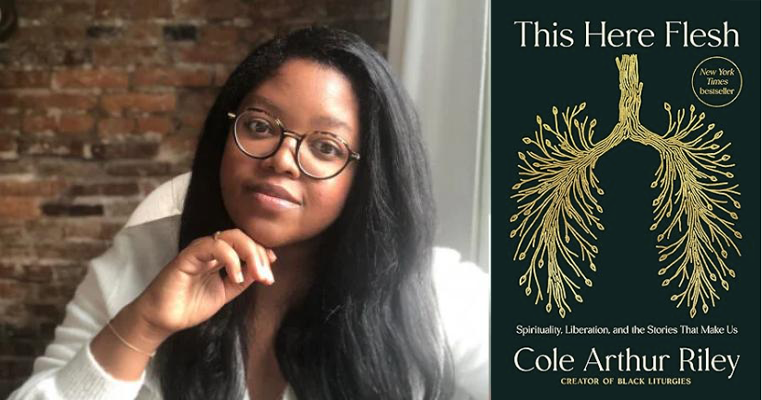

Review: This Here Flesh: Cole Arthur Riley’s Gentle Revolution

Cole Arthur Riley first shared her words with the world, anonymously, through the Black Liturgies Instagram account. Offering short, embodied liturgies that invite readers to “inhale” and “exhale” into affirmations of selfhood, divinity, and hope amid doubt, Arthur Riley draws on a wealth of Black theologians, activists, and writers as well as her own lived experience.

This same reverence for human dignity and embodied spirituality is the throughline of her debut book This Here Flesh: Spirituality, Liberation, and the Stories that Make Us. She now steps out of anonymity to share deeply personal stories from her own and her family’s lives, a rich tapestry that draws readers into the profound teachings of rest in a chronically ill body, of unravelling injustice in a Black body, of everyday wonder and the importance of lament. Arthur Riley is an expert storyteller, gently leading readers toward the truths always at the core of us, even when they are hidden by the systems that would imprison us.

This Here Flesh begins with Arthur Riley’s central principle of dignity, the unshakeable belief that dignity is something that cannot be earned but is inherent to every human being. She writes, “Our dignity may involve our doing, but it is foremost in our very being – our tears and emotions, our bodies lying in the grass, our scabs healing.” Interpreting parts of the early Genesis stories, she describes a theology of diversity in which “it is not an individual but a collective people who bear the image of God.”

Confronting a colonised conception of place, Arthur Riley considers the “mysterious entanglement” between human wellbeing and our connection to where we are. She writes, “I think it is one of the deepest evils to become a thief of place… It’s the work of people incapable of perceiving their dignity without attempting to diminish someone else’s.”

Arthur Riley describes the disconnect from her body that she has experienced in many faith spaces and how this has been used as a weapon of white supremacy. “I think whiteness knows that the more detached I am from my body, the easier that body will be to colonise and use toward whiteness’ own ends,” she writes. And so, in her spiritual work, embodiment has become a central practice. Arthur Riley argues, “We cannot get free disembodied… We may forsake the body in order to survive, but the truth is that we do so at our own peril.”

Memory is deeply important to Arthur Riley, as she weaves profound truths from the stories of her father and grandmother, and laments the collective memory lost when her ancestors were stolen from their homes and brought to the United States to be enslaved. She engages in different forms of remembrance, epitomised by the practice of Communion. “The Christian story hinges on a ceremony of communal remembrance. This should train us toward an embodied memory,” she writes.

Awe is described as a force of liberation in This Here Flesh. “Wonder requires a person not to forget themselves but to feel themselves so acutely that their connectedness to every created thing comes into focus,” Arthur Riley writes. Similarly, in her chapter on fear, she discusses its sacred potential “to mould us into people engaged in the unknown” and the compassionate way God responds to our fear. Instead of bidding us have courage, God “draws us toward fear’s essential sister, rest – a sister who is not meant to replace fear but to exist together in tension and harmony with it.” She describes how rest is not a reward but “the path that delivers us” to liberation.

For Arthur Riley, “True lament is not born from that trite sentiment that the world is bad but rather from a deep conviction that it is worthy of goodness,” and it is something in which God participates with us. The gospel story of Jesus’ rampage through the temple, overturning tables, is for her a lesson in embodied rage and its relationality. She writes, “What freedom it is to witness a God whose primary concern is not for how he makes the oppressor feel, but for feeling alongside the oppressed, and telling the truth about it.”

This Here Flesh offers a refreshing reminder that justice does not dehumanise one party in favour of another but honours the dignity of every person. Arthur Riley argues, “True justice has little concern for good and bad, and is much more interested in protecting and affirming dignity with tangible actions and repair.”

This repair is essential in the wake of injustice. She writes, “If we are to be reconciled, the offender must become disturbed by the state of their soul – a contrition that births apology not for the sake of its own forgiveness but to honour the dignity that was once at risk.” And amid the work of restoration: joy, which is both a remembrance of injustice faced and “an honouring of the liberation that has come.”

In the final chapter, Arthur Riley considers liberation “not a finality or an end point; it is an unending awakening.” She discusses the ways in which liberation is in an internal, embodied process as well as a relational one. “We do not need to pine after the power of our oppressor; we have only to long for our own power to be fully realised,” she writes. “Liberation recognises that I won’t get free by anyone else’s bondage.”

In This Here Flesh, Cole Arthur Riley invites readers into vital lessons about connectedness – to ourselves, our bodies, to creation and community, to the sacred. Her words are moving in that something within the reader is asked to shift, to change, to go deeper. It is impossible to read this book without being transformed by it, newly equipped to find hope in a world we often disregard as broken and to find compassion for our shared brokenness, knowing we all deserve better.

This Here Flesh is available for purchase in bookstores, and just this week Arthur Riley has released Black Liturgies: Prayers, Poems, and Meditations for Staying Human, which compiles and expands on much of her liturgical work on Instagram.

Gabi Cadenhead is a poet and composer, and mission worker for Christian Students Uniting at the University of Sydney.