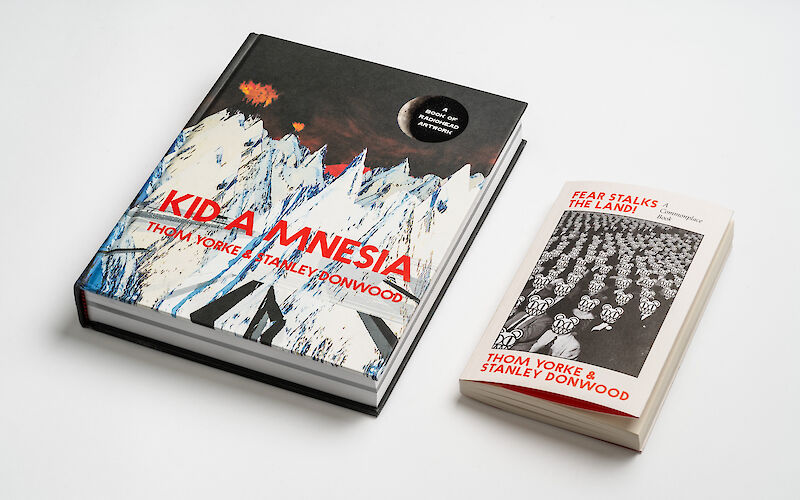

Reviews: Kid A Mnesia & Fear Stalks the Land! A Commonplace Book by Thom Yorke and Stanley Donwood,

As Stanley Donwood also points out in his other recent book of (mainly) Radiohead-related artwork, There Will Be No Quiet, the making of album visuals is integral to the overall process of music-making for Radiohead, with Donwood typically painting and drawing during the recording process – going with the flow of creativity to come up with, in parallel, artwork that reflects the music. The art is not incidental, but rather a part of a larger package, as when Yorke and Donwood gave away a satirical newspaper on the streets of London to publicise the album The King of Limbs.

Donwood is, dare I say, like a sixth member of the band, or, if that spot is already taken by producer Nigel Godrich, a seventh. Thom Yorke went to art school with Donwood, and the visual art is often collaborative – they point out how they ‘finish’ each other’s paintings or work on similar subjects simultaneously. For the albums Kid A and Amnesiac, recorded in and around 1999, they jointly worked on artwork, encouraging each other by sending each other drawings via (ye olde) fax machine.

Twenty years on, Radiohead have re-released the albums, the results of the same recording sessions, as one fat, extended package, as well as an exhibition and a couple of books. Just as the inclusion of B-sides, demos and rejected songs gives insight into the process, the two books throw a light on the development of the words and images.

In the introduction to the larger book, Kid A Mnesia, a glossy and gloomy collection, Donwood says that the pictures seem like ‘the diary scribblings of a couple of mad people’. The images were not meant to be permanent, just a part of their own, private process. The only permanency was meant to be the cover and sleeve artwork. So not all images are potentially iconic, but you are given a look into the popping up of ideas, the manipulation and creep of images until something starts to seem right – as with the music, the pushing until the light bulb comes on. And, as with iconic albums (see Beatles documentaries), there is public interest in the process, not just the result.

Part of the idea of Donwood working in the same place as the band as they were recording was to, according to Donwood, accomplish the perhaps fiendishly difficult task of trying to ‘extract what the music looked like’. (Donwood relates hilariously in There Will Be No Quiet how difficult this often was.) At the same time, Yorke and Donwood were reacting to what was around them. Yorke says he was burned-out by the enthusiastic reaction to OK Computer, and the British triumphalism of the likes of Tony Blair, Oasis and the over-blown Young British Artist movement that had infected British society, along with the new intensity of spin and surface.

Yorke describes drawing landscapes (in typically bleak fashion) as a way of dealing with creative block and exhaustion, and as a cleansing after the relentless weirdness of the world tipping over into the next millennium. Yorke says he felt assaulted by voices from terrorists to CEOs, from the chatter of contemporary life – mostly false and shallow. Donwood became obsessed with London as labyrinth – his minotaur became a weeping cartoon character. This, recall, was even before 9/11 – Radiohead had a large capacity for focusing on the half-empty glass (though there is dry humour in it). You don’t go to Radiohead for solace, but they do reflect the confusion and impotence of the age, and the question of whether art is up to the job. Yorke says the process was about searching for something true amidst all the Orwellian propaganda. Journalist Gareth Evans, in an essay tucked into the middle of the larger book, says that like the novelist Don DeLillo, Yorke was trying to find a way to stand outside to observe, while still being unavoidably within (the labyrinth).

The crudity and anger tumbled into the design reflects the music – the disillusionment comes out choked and stuttering. As music reviewers harped-on at the time of the original release of Kid A, the music had cut-and-pasted lyrics and samples, and was disjointed, reworked and processed, to emphasise texture. (This is not to say that it lacked beauty – the first two songs of Kid A are ethereal, Knives Out is pretty.) The accompanying artwork of manipulated images are crude in pixellation, but this makes them textured and abstract. (At the time Donwood was playing with burgeoning computer programs for image manipulation.)

There’s a collision of (then) new tech with repurposed old style – like the woozy jazz of Life in a Glasshouse – photocopies of blocky buildings, redrawn Piranesi labyrinths, collaged and typed over to look like government reports on the apocalypse. Then there’s the juxtaposed fire and ice landscapes, with video game mountains and ominous lack of human presence, slashed across like the corrupted result of a faulty printer, like metastasized graphs. The artwork mimics the inconsistent, mashed-up, distorted contemporary space. Yet, interestingly, Yorke says that despite all this there’s a cohesion to all the art – that process thing again, but also, I suppose, collage can become one coherent work of art from a distance.

There’s also the cartoony side – Donwood’s iconic angry bear, the minotaur from the Amnesiac cover, the odd comic strip segments, the leafless trees like wraiths (the latter a perpetual motif for Donwood), and the text-heavy posters that take a hint from advertising around 1900 but point to the vacancy of words, of phrases where meaning has been lost. And, indeed, the small paperback Fear Stalks the Land! (subtitled A Commonplace Book – a commonplace book is a traditional way of journaling wisdom) has a kind of wisdom to it, but its collection of poetry and lyrics used or discarded for the albums (embellished by black and white Yorke and Donwood scribbles) points to Yorke’s frustration with the Orwellian uses of language, how words can hide and obfuscate, here amplified by an anomalous use of footnotes.

It’s all of its time, technologically and style-wise, responding to Blair, Yugoslavia and the possibilities of the internet, but it’s also prescient and prophetic. Things haven’t exactly got better, as Donwood suggests. Just now, the fire and ice, the stark trees and red skies, remind me of Ukraine; the cartoon monsters of Putin, Trump, Erdogan and al-Assad and all the other shark-toothed politicians. Then there’s the threat of ecosystem collapses, the domination of management and ad-speak, the shouting match of Twitter. Yorke and Donwood’s exasperation remains sadly relevant. Happy reading!

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.