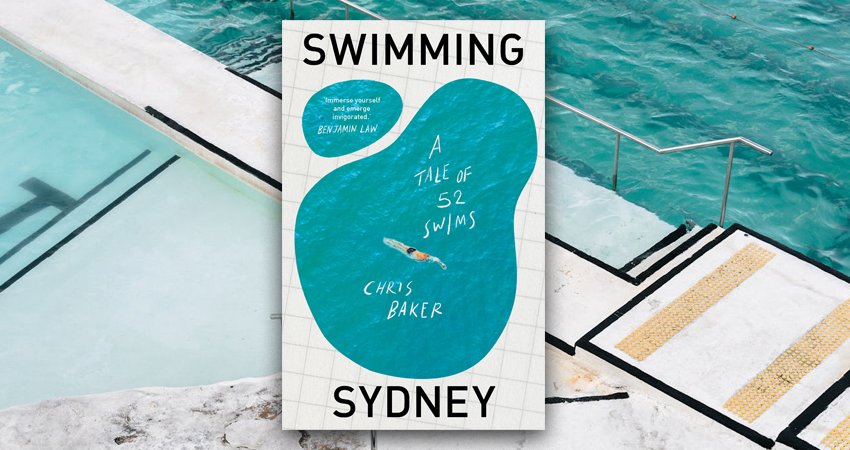

Review: Swimming Sydney, Chris Baker, Newsouth

Swimming, claims Chris Baker, is one of the biggest pleasures of living in Sydney, a city, more than most, whose identity is inseparable from the water which surrounds and penetrates it – the beaches, the harbour, the rivers, the pools. Even though many Sydneysiders don’t live by the beach, a common vision of the city is looking out over water.

In this book, Baker writes with a framework of a year of weekly swims. There is much to learn about Sydney’s history, beyond just Baker’s way of evoking the calming feel of being in the water. Swimming can be an almost mindless activity – in a good way – but swimming prompts him to think about race, gender, sexuality, class, economic inequality, illness, life and death.

Despite the disparities in wealth of its residents, water views, at least temporarily, are accessible to most. And Sydney is a city set up for outdoor swimming, whether that be prominently, at tourist hotspots like Bondi or Manly, or at the many public pools that are hidden gems, like Murray Rose Pool at Cremorne, which retains an egalitarian spirit, despite being surrounded by the art deco apartments and mansions of the wealthy, blessed by views of the Opera House, with free entry, and set in gardens. Of course, the rich can afford their own pools, but at the beach or public pool, stripped down, there is a levelling.

We are made of water; there is something primal, childlike and reassuring about swimming. It is also good for health, sending blood to the brain (perhaps because of the pressure of water on the body), helps with motor skills in the elderly and takes away tension. Water offers relief after a hot, sultry Sydney summer day, or just from the stresses of modern life. Swimming is therapy – there are swimming groups for babies, the elderly and asylum seekers. Baker repeatedly writes about the power of swimming for washing away problems.

Likely for these reasons, the city invested in pools during the depression – many public structures date from then and have a quirky and vintage charm and are beloved. Baker splashes about at Murray Rose Pool, amongst the flaunted bodies and art deco, at the Dawn Fraser Pool in Balmain amongst autumn leaves. Sydney’s pools are named, appropriately, after swimmers – there’s also the Andrew Charlton Pool and the Ian Thorpe Aquatic Centre.

Baker notes that bodies of water have differences in feel, just like places on land. They evoke memories and contain stories. He recalls the poem ‘Five Bells’, commemorating a drowning. (The poem inspired John Olsen’s mural in the Opera House.). Baker then writes about how his own grandfather drowned in Sydney Harbour under similar circumstances.

Sydney is famous for its beaches, and Baker writes about Manly, Clovelly, Bondi and Bronte, but he also swims at lesser known places, like Parsley Bay Reserve in the east, situated off the harbour as you crawl up the peninsula of South Head, a hidden gem with a suspension bridge across what looks like a river but is simply an arm of the harbour that abruptly ends (or begins) with a pale semicircle of beach.

Travel a bit further, and there is the insular community and expansive beach of Palm Beach, a drawcard for film and TV series makers. MacMasters Beach, near Gosford, is where one can feel fringed by wild bush, even though it is not far from civilization. The same goes for the south: at Royal National Park there are Garie Beach and Burning Palms. The latter is accessible only via a long walk, but recently the Figure Eight pools have become a social media sensation, meaning queues for snapshots, hundreds of examples of which are already on the internet anyway. Baker muses ironically on the shift in status, from an area which, decades ago, was a haunt of the ‘exiled poor and marginalised’.

In between the suburban pool and the wild beach are Sydney’s ocean pools. Sydney sandstone seems to lend itself well to the ocean pools, and they combine the best of both worlds – a place where one can do laps if one chooses, but where one is also more exposed to the elements, to crashing waves and sea life. At Bondi Icebergs, one of the city’s most famous, winter swimmers are equally famous for their seeming self-mortification through exposure to the frigid ocean water, but they insist on the health benefits of an icy dip.

Clovelly is the biggest of the ocean pools, with lots of sea life. Wylie’s Baths, Baker’s favourite, partly because it has resisted the slick upgrades which seem to dominate other areas of Sydney, is one of the city’s oldest. Again, it is named after a famous, competitive female swimmer.

At McIver’s Ladies Baths, it is female swimmers only, despite antidiscrimination lawsuits (one of which was beaten by fiercely aquatic nuns). Baker likes the fact that he will never swim here, because it is another example of a pool that brings community together, in what the women feel is a safe, egalitarian, nonjudgemental environment.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.