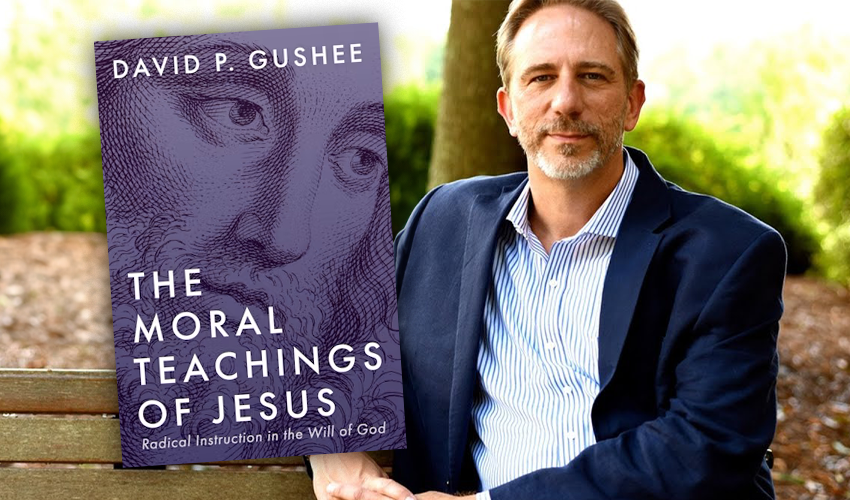

Review: The Moral Teachings of Jesus, David Gushee, Cascade Books

David Gushee is a prominent Christian ethicist who, in The Moral Teachings of Jesus, sets aside for a moment issues of atonement and other doctrines that were later developed by the early church and are a particular focus for Protestants, and concentrates on the sayings of Jesus that circulated and then were written down in the gospels, and what they say about Jesus’ moral orientation.

This moral orientation is largely contained within the phrase ‘the Kingdom of God’. Jesus suggests that status is all-consuming, and we build societies around this, instead of around generosity and care. For Jesus, an obsession with status and resulting inequalities is not the intended way of things, but an upside-down kingdom, and the Kingdom of God is a turning of this world right-way-up. This may look radical: it is a holistic approach that privileges justice, mercy, peace and love.

Of course there is a long history of commentators claiming to discover the essence of Jesus’ teaching, from Luther and Calvin to Reinhold Niebuhr to John Piper, but reading the gospels in their entirety reveals Jesus’ constant insistence on total, counter-cultural transformation – more than attending temple or church once a week. Jesus’ approach is a whole worldview, therefore it involves wholesale change. Because of this, Gushee notes, Jesus warns that his teachings are hard and only a few will tread the path. (Those who lament the loss of widespread, public acknowledgement of Christian belief might do well to remember this.) And this involves an inner moral orientation, rather than just holding particular beliefs.

Jesus’ assumption, Gushee writes, is that the whole economic system is corrupt. (And the cleansing of the Temple story indicates that religion can be complicit.) Jesus’ focus is rather on the marginalised of his day: the poor, the sick, children, women and foreigners. He teaches by example, reaching out to them, including them. He views them as worthy and recognises that societal structures cause them to be marginalised. Importantly, Jesus seems to understand that their marginalisation pushes them into behaviour frowned upon by society, whereas the rich can afford to seem to be law-abiding, while reinforcing structures that allow them to take advantage of others.

As is often noted, Jesus has much to say about money, while his followers make much effort to avoid the harsh conclusions. Gushee suggests that the story of Lazarus and the rich man – where the suffering of poor Lazarus has been ignored by the rich man in this life, and when they both die it is Lazarus, not the rich man, who is rewarded – is the culmination of Jesus’ teaching. Gushee notes how naming the homeless man but not the rich man is further evidence of Jesus’ turning the world upside-down (or right-way-up, as it were). And a further point is that Jesus’ moral teaching about wealth will be consistently ignored.

Despite the confronting nature of Jesus’ moral teaching, Gushee suggests that Jesus is consistently positive. In the Beatitudes he intensifies Jewish law (rather than discarding it), reinterpreting it to deepen it, and rather than just listing ‘thou shalt not’s, he offers ways of peacemaking and building relationships. He understands that the threat of punishment is not enough for the coming of the Kingdom.

And yet Gushee’s (and others’) reading is challenging for Protestants. Not only does he suggest that Protestants may have their own forms of legalism, but he warns that Jesus’ teaching is more sophisticated than simply grace over Jewish legalism. The point of the parable of the Pharisee and the tax collector may be, says Gushee, more complex than what Protestants think of as grace, with the tax collector, unlike the Pharisee, recognising that a complete moral turnaround is necessary. It could also be that the tax collector, unlike the Pharisee, may be realising his part in systemic inequality.

Jesus is overwhelmingly attentive to moral action; he just insists that the moral life is more than not breaking the law – it is about, in big and small ways, putting oneself second and reaching out to others. The moral of the Good Samaritan is that we can’t simply walk by when we see the suffering of our neighbours, no matter what doctrines we hold. Jesus’ version of the Golden Rule, says Gushee, is that, more than just offering like for like, Jesus challenges us to treat others well no matter their treatment of us. This takes discipline and a rejection of pride.

Related to this is Jesus’ undifferentiated welcome of others. He suggests it is not our role to judge, but God’s. (This is another lesson of the parable of Lazarus and the rich man.) We are living in a mixed, messed-up world where, importantly, good and bad is mixed within each individual. It is arrogance to think that we are good while others are bad. Encouraging moral behaviour is essential, but Jesus does this not by judging but by showing examples of kindness, humility and tolerance. And he does this to such a radical degree as to shock his hearers into recognition.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.

1 thought on “Radical Kindness, Humility and Tolerance”

Dear brethren in Christ, our hearts is spiritually touched with your encouragement reading from your website kindly please share more with us and help us with your teaching materials for they will help us in our fellowship here and win more souls to Christ Jesus we pray and request you kindly if you have Bibles to send to us that Lord will lead you to come and share the word of God with us we hope that God bless us to share more in his kingdom and pray for the orphans who I TAKE CARE OF AND worship with THEM happy to read from you in Jesus name. . PASTOR moanga KENYA