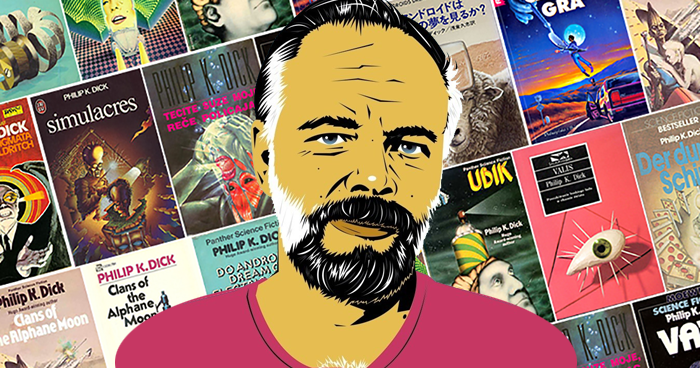

Philip K. Dick was a prolific American author, most widely recognised for his Science Fiction novels and short stories. With 44 published novels and over 120 short stories, he explores a wide variety of topics including war, alternate histories, corporate greed, corrupt governments, drug use and human nature. His works are philosophical and reflective, inviting the reader to think further on issues. He rarely has a happy ending and stories are often concluded before a final resolution, leaving one to extrapolate possible endings to the narrative. Philip K. Dick asks big questions of the human race, making his writings a fruitful conversation partner for theology.

Despite his prolific writings, his name is not a commonly recognised one. We might be more familiar with the movie and television adaptions of his stories. The cult classic Blade Runner, which centred around the humanness of artificially intelligent replicants, was based on the novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? The action-packed Minority Report was a short story of the same name questioning the nature of crime if it could be predicted. The cleverly animated dystopian A Scanner Darkly was a novel first, as was the recent television series The Man in the High Castle, which won the Hugo Award in 1963, and explores an alternate history where the Nazis and Japan win World War II. Most recently, several of his short stories have been turned into single episodes in the television anthology series Philip K. Dick’s Electric Dreams, the only adaption to bear his name. Twenty three of his works have been adapted into movies and television series. Not surprisingly, however, many of the adaptions veer away from the original stories.

One defining aspect of Dick’s works is that there are no heroes. The people that populate his stories are everyday, common people. A repair man, a shopkeeper, a common soldier returned from the war. While his stories may contain heroics, they are just as often about disturbing aspects of human nature. The repair man turns out to be from the future trying to repair an electronics unit that will brainwash humans into subservient compliance. The shopkeeper turns out to be able to control time and space but uses her ability to monopolise a group of people needing to escape a dying, poisoned world into buying her produce. The soldier is struggling with life after the war and is unsure as to the purpose of the boat he is building in his backyard, until the rain starts falling. You are left suspecting that it is an ark story.

Philip K. Dick’s characters are flawed, real, gritty. They are unashamedly human, much like so many of the Biblical characters. The Twelve Disciples are a rag-tag bunch of fishermen, tax collectors and zealots. Yet, they were used, along with multitudes of nameless followers, to change the course of human history. David, a shepherd turned king, was also an adulterer and murderer. Yet, he is called a man after God’s own heart. Saul, a Pharisee and persecutor of the church, became one of its earliest allies and has a name change to reflect the internal change. No one is excluded as a valuable character for Dick’s stories, just like no one is excluded from being able to be used in God’s loving and grace filled mission on earth.

One of the common themes in Philip K. Dick’s works is that of human nature. He asks the question, what does it truly mean to be human or, as Steven Owen Godersky clarifies, ‘What is it like not to be human?’ In Human Is, a short story that was adapted for the Electric Dreams television series, a woman struggles with an abusive and emotionally cold husband. He is dispatched to a mission off world, but he returns a changed man. His body has been possessed by an alien entity who proves to be a loving and caring partner – a far better example of a man, than the human it replaced.

In Scripture we see the perfect example of being fully human, but only in the incarnate Jesus. The one who is fully God is also fully human and displays the grace, forgiveness, compassion, and strength of character that humans are meant to strive for. Our humanity, on the other hand, is full of brokenness, failure, mistakes, and dehumanising tendencies. Christians are called to be ‘little Christs’ but there is a full awareness that this cannot be achieved through personal effort alone, but only through the work of Christ in one’s life.

Philip K. Dick’s understanding of science fiction was that it was not merely about the future, nor ultra-advanced technology. Rather, science fiction was about a fictional society that only differed from our own by a dislocating idea.

The conceptual dislocation – the new idea, in other words – must be truly new…and it must be intellectually stimulating to the reader; it must invade his mind and wake it up to the possibility of something that he had not up to then thought of.

While the Biblical message is certainly not science fiction, it does contain a conceptual dislocation, an idea truly foreign to the human mind. It contains a message of good news, of hope, of fulfilling and perfect relationship with the Creator of the universe, despite our imperfections and failings. A message which sees that Creator take on human form, dwell among us and show us a different way of living that involves loving one’s enemies, caring for the least, standing against injustice and walking with the one who is fully human.

Dr Katherine Grocott

2 thoughts on “Philip K. Dick and Scripture in Conversation”

I love science fiction and especially Philip K Dick’s Blade Runner and Minority Report. Those flawed characters and the new ways of seeing the future are fascinating and thought-provoking. The Bible certainly does at times seem like a work of mystery or science fiction, with a host of interesting and diverse characters and storylines. And the end of this epic story could also have some surprises in store as we journey to “a new heaven and a new earth,” another planet or universe even? An interesting comparison by Dr Katherine Growcott.

Dr Growcott’s article on PKD acts as both commentary and tribute. Having been collecting Phil’s work and reading it for over 40 years, I feel confident in both applauding her appreciation and in feeling that she has apprehended many of PKD’s core concerns. An avid student of theology and philosophy, Phil’s work is as yet, too complex to be embraced by a Hollywood too facile to entertain the spiritual writings of a man who had read Plato and knew of the “cave” problem, who had read French and Russian literature and who, in the Valis trilogy towards the end of his life, explores the nature of both true consciousness and true spirituality. Thank you Dr Growcott in perceiving the importance of PKD as few do.