Review: Devil House by John Darnielle

In the 1980s there was a so-called ‘Satanic panic’ – hundreds of cases of supposed physical and sexual abuse linked to Satanic cults. This was often linked to moral concerns over youth culture – violent video games, music, art, drugs. Later, many of the allegations were disproven, with blame being placed on psychotherapists dredging up repressed memories of abuse – abuse that often didn’t happen but that victims imagined through the prompting of therapy. The story was not as it seemed.

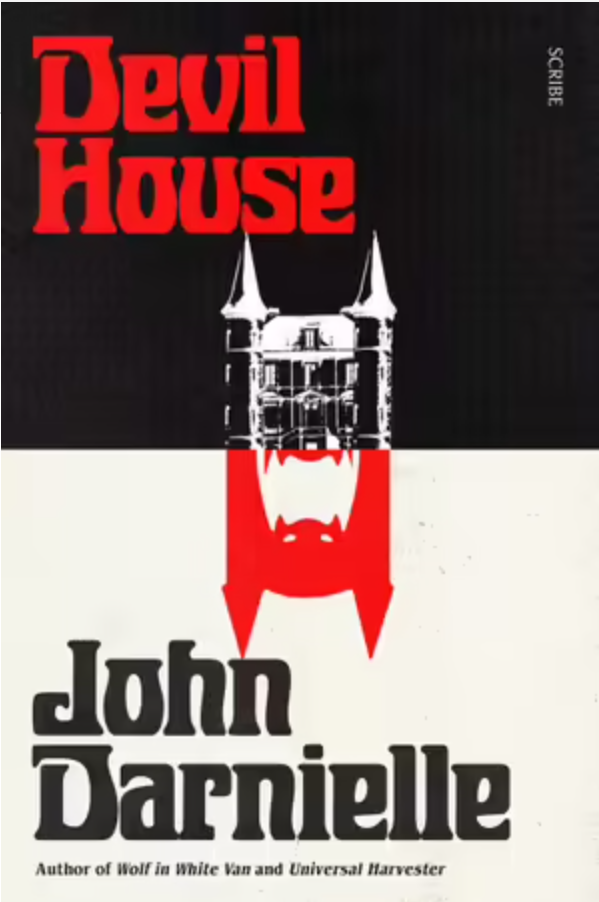

John Darnielle’s Devil House riffs on all this in a way. This is the Mountain Goats singer’s third novel, more sprawling than the last, but with a typical interest in odd and gothic themes, not to mention 80s and 90s tech and pop culture. It is a kind of fictional true crime story. Darnielle’s protagonist and narrator Gage Chandler is a Californian true crime writer who has had moderate success with his books, some of which have been turned into films. His most famous book concerns the 1980s case of a ’white witch’, in reality a respected schoolteacher who murdered two teenagers who broke into her house in self-defence, but who then went a bit over the top, let’s say, in the aftermath. Tabloid reporters seized on some minor details and portrayed her as an occultist.

We hear about this case and book as background to his latest topic, which is something of a reversal of the White Witch case – a respectable couple is killed by fringe-dwelling teens. Or so it seems. The case is unsolved.

The Devil House is a building in a run-down part of town. Previously a café, then a bookstore, by the 1980s it has become a failing X-rated video store. It is then abandoned but is frequented by a group of misfits who use it as a hang-out space, decorating it with paintings of knights, monsters, demons and the like. You can see the potential building for the misidentification of cultish tendencies.

The owner and a prospective buyer are murdered one day when they make an inspection of the building and surprise the squatters. Decades later, alerted by his editor to the potential the case has for a book, Chandler buys the house to begin what turns out to be an obsessive load of research. He rips up carpet, buys old crime scene photos online.

Being John Darnielle, he gilds the teens’ story with medieval references, and even includes a short chapter, printed in gothic script no less, that seems to have a tangential relationship to the story – a fairy story or mythical tale perhaps prompted by Chandler at one point thinking of his (and Darnielle’s) characters in medieval terms.

In Darnielle’s previous book, Universal Harvester, he played with the subjectivity of perception, alternate timelines and multiple angles. (He wrote, ‘In some versions of this story…’ and ‘a variation on this story…’) We are barely started with this new novel, and Chandler is talking about the way his story ‘could have’ gone, and about ‘wrinkles in time’, setting up expectations of multiple viewpoints and puzzles to solve.

More than just a crime story, the book is about the art of writing true crime – or any history, really – what audiences expect, how much liberty you can take with the story and characters, what angle to take, what to exclude, how there is always a danger of caricature and falsely reading motives and causes, and of simplifying into villains and heroes, dragons and knights and fair maidens. In real life, things are sometimes messy. Most times, the perpetrator is also a victim. Chandler sees himself as a truth-teller, but the aftermath of the White Witch case suggests that, like the tabloids, he is in danger of distorting and sensationalising.

In all this, the book is elevated above the coldness of much crime writing. Darnielle has sympathy for the marginalised and the victimised, the homeless and the disturbed. He is interested in issues of belonging. Where some writers would fall into characterising the relationship of the father and son in Universal Harvester as fractured, Darnielle gives it tenderness. In Devil House, there is a subtle understanding of the nature of outsiders being drawn to one another. And, as with his music, he is able to give the gruesome – and some of the story is gruesome – a comic and warm edge.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.