Uniting Church Minister Rev Dr. Amelia Koh Butler brings a balanced view on the marriage discussion as Australia awaits the voluntary postal vote on same-gender marriage. You can follow her regular theology driven reflections through her blog Hyphenated Faith.

Disentangling the threads of argument and obfuscation may need a bit of work at this point. The public is being told (by some) that a Government-funded plebiscite, about whether or not we should have same-gender marriage, involves a debate about Christian marriage. It does not. It is about who has access to particular legal rights in Australia. This debate is a debate for all Australians. What kinds of rights and freedoms do we expect people to enjoy in this country? Who should have access to such rights and freedoms? Are civil rights determined by popular opinion or by considered wisdom?

Religious influence?

If we were to argue for a religious view of marriage to have a determining influence on Australian law, we would be arguing that Australia is a religious state, rather than a secular nation with religious freedoms. Indeed, freedom of religion has been the foundation for settlement history in places like South Australia, where Lutherans became free settlers. Likewise, among the earliest settlers were Chinese, who were initially Confucianism or Buddhist.

If Australia is to be a religious state, then some of our taxes should go to religious organizations to provide services for the state. If not, let’s recognize the implied separation between Church and State.

First Nations?

If we cast aside colonial Christianity and migrant religions, we might ask what First Peoples in Australia have to say about marriage. This invites broader conversations about kinship and complexities of relationships with people and land. None of these deep, millennia-old understandings has been considered in the current legislative approach. What we do know is that many First Peoples live together in relationships, recognized by their communities. Indeed, the Northern Territory has strong de facto recognition, precisely because of the large number of people who have chosen not to follow the colonizers’ forms of marriage control.

At the time of a Roman Census, Joseph and Mary travelled to the town of David to be registered, primarily for Roman governance purposes. By legislation, the state controls have been used to manage populations. Work, housing, education, health-care, transport and social support systems are designed around those who are registered – at least, those who have the right to be registered. What happens when people gather informally? What happens when we do not recognize who is present and how they relate to one another?

Invisibility is de-humanizing

In 1833, the British Empire abolished slavery. In North America, slavery was progressively abolished between the late 1700’s and 1865. Abolition came at the cost of many lives and a significant Civil War. Slavery also existed in Australia. There are photographs of Aboriginal labour and Blackbirded labour (Pacific Islanders) men in chains that were forced to work, establishing colonial power and economy. We don’t talk about slavery in Australia. We like to think there are no sweat-shops or trafficked sex-slaves or Filipino farm-brides. As long as slaves are invisible, we can pretend they are not really there.

In the same way, we try not to name asylum-seekers. We try not to call them refugees. We avoid telling or hearing their stories. If they have names and stories, we might begin to recognize their humanity. We might begin to think we have a responsibility toward our fellow human beings. As long as they are nameless, we can lose them from our consciousness.

Coming out

This has been part of the “problem” recently: we have discovered people with names who can no longer be dismissed. A Prime Minister was not married to her partner – what was his name? A Senator is a mother and has a wife – surely, we cannot imagine her as a national Treasurer? Even if we can dismiss these public figures, we cannot so easily dismiss the sister or son, neighbour, parent-of-my-child’s-best-friend, work colleague or carer. We know their names. We cannot so easily forget them.

When our friends and relatives started coming out of the closet, every family “had one”. We all coped. We made jokes about quiches, interior decorating and overalls.

Humour, in all its tastelessness, allowed people to hide their insecurities behind a smirk and a giggle.

There were of course real questions. Generally, these remained unasked and unaddressed, unless it was late at night in the privacy of a lounge room over a glass of port. Such conversations were well removed from the public sphere.

Therein lies the challenge: how do we enter the public sphere? There is to be a national plebiscite. It will take the form of a non-binding postal survey, without safeguards or courtesies. Within hours of its announcement, verbal and social media abuse was normalized.

Prophesy or perish

As a religious leader, I believe there are prophetic words that should be spoken into the nation. Prophetic words speak into a community about the consequences of certain behaviours and actions. Whenever we preach or proclaim spiritual truths to the world, we are striving to use a prophetic voice. The prophetic voice may be suggestive or influential. It seeks to speak truth and wisdom. It may come across as brutally honest. However, it is not coercive. It is not the role of the prophet to cast judgement. It is the role of the prophet to remind the community of God’s Creative, Reconciling and Life-affirming characteristics and call people to adopt holy values.

- Do no harm.

This is not a self-centred approach to avoiding any harm to yourself. This is an attitude of recognizing “the other” and taking into account whether they may be harmed by your action or inaction. Allowing harm to take place leads to our own diminishment. We become less human as we de-humanize others.

- Do not judge (Do unto others as you would have them do to you)

Human beings do not get to play God. We do get to be defined and redefined by God, but not by people. Each of us is accountable for our following of God’s ways. God takes that seriously enough and doesn’t really need us to act as judges.

- Seek blessing – for yourself and others

Blessing means to call the best out of. God seeks to bless Creation (including us and others). God works toward blessing. This started with creation, continued with the reconciling work of Jesus Christ and goes on through the Spirit. Calling the best out of others involves getting to know and love them, praying for them and seeking God’s light to shine upon them.

Prophetic work acts like a wildcard because we don’t control God’s activity. Rather, we wait upon whatever God sees fit to inspire and actuate. Recognizing God’s activity as being beyond the control of humanity’s challenges the idea that Church can ever really serve the State without running into a conflict of interests.

Let’s get out of being agents of the State

I argued the same case in 2001 when a UCA Minister “illegally” married two people in Villawood Detention Centre and I was carer for the young wife during her pregnancy.

- Civil law about marriage is most certainly not Christian.

- Church involvement in state legalities is dangerous and gives a false bias toward the concept of religion and state being together on other things.

- We should not be involved when we do not agree with the state and we should be able to offer full religious rites when church and state disagree too.

- If religion and secular state are to be independent of one another, different religions may be free to recognise polygamy (as Anglicans do in Sudan and Buddhists do in parts of Asia) and they may choose to accept or reject interfaith marriages based on the kinds of vows and covenants that take place (as happens in Indonesia).

Some religious groups will choose to narrow who they bless by gender identification or sexual orientation. Some may struggle with the challenge to better understand their own community needs, where many of our groups have third gender or designated gendering.

Space for Grace

Space for Grace provides a method for community discernment. It was developed over several years among culturally and linguistically diverse leaders, seeking to find ways to stay in community relationships, despite different backgrounds and world-views.

The concept of Space for Grace is:

- Establish a common discipline of creating a “grace margin” that may take us beyond our normal boundaries of safety – this can be done with a trusted facilitator who assists in holding people to respectful behaviours.

- Form community of respectful listening, using mutual invitations to speak – allow room to listen – don’t deconstruct as if stories can be treated objectively – accept that they are subjective.

- Identify themes in common and of differences to be further explored.

- Break bread together, covenanting to keep each other’s stories as sacred.

- Continue to research together (beyond the initial subjective stories) – identify what can help people to pursue discernment while still maintaining respect

… after that, groups usually get imaginative about what they might do next. Several groups I have worked with have entered into relational covenants and made commitments about what kind of relationships they can continue to pursue.

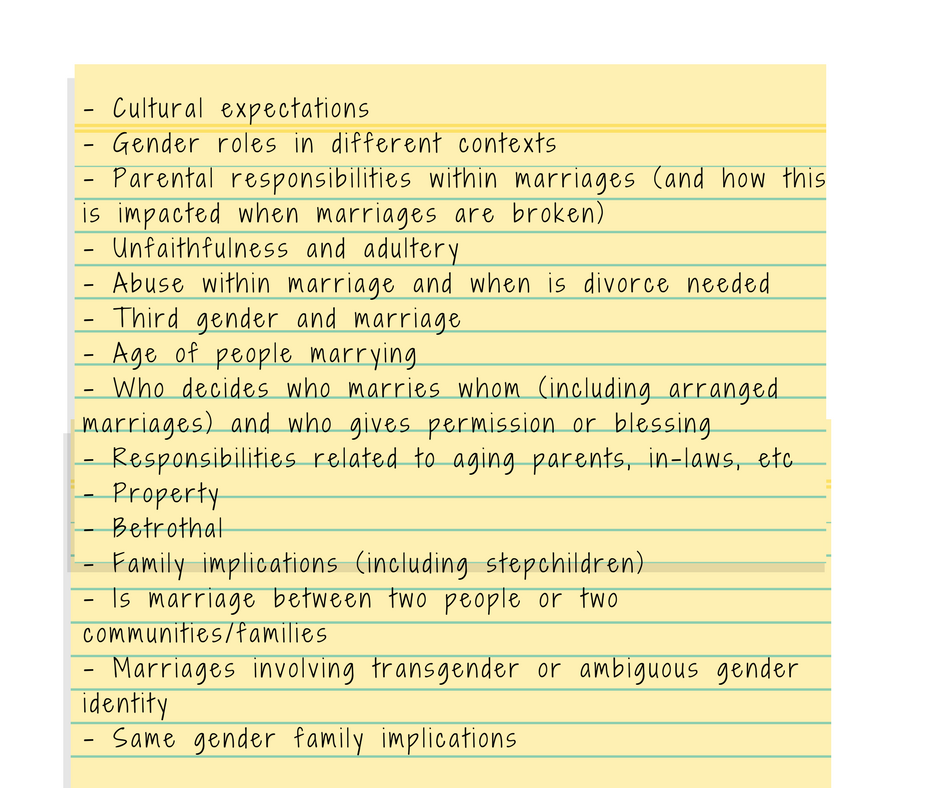

In the early Space for Grace conversations about a Christian Theology of Marriage, a very diverse group identified a range of issues to be explored:

Many of the stories shared were from people who came from countries where civil marriage was then followed by religious rites or ceremonies or blessings – e.g. Indonesia.

Indeed, the GKI Church in Indonesia had a very big conference about Same Gender Marriage a few years ago.

None of those conversations was about shutting down conversations about civil marriage.