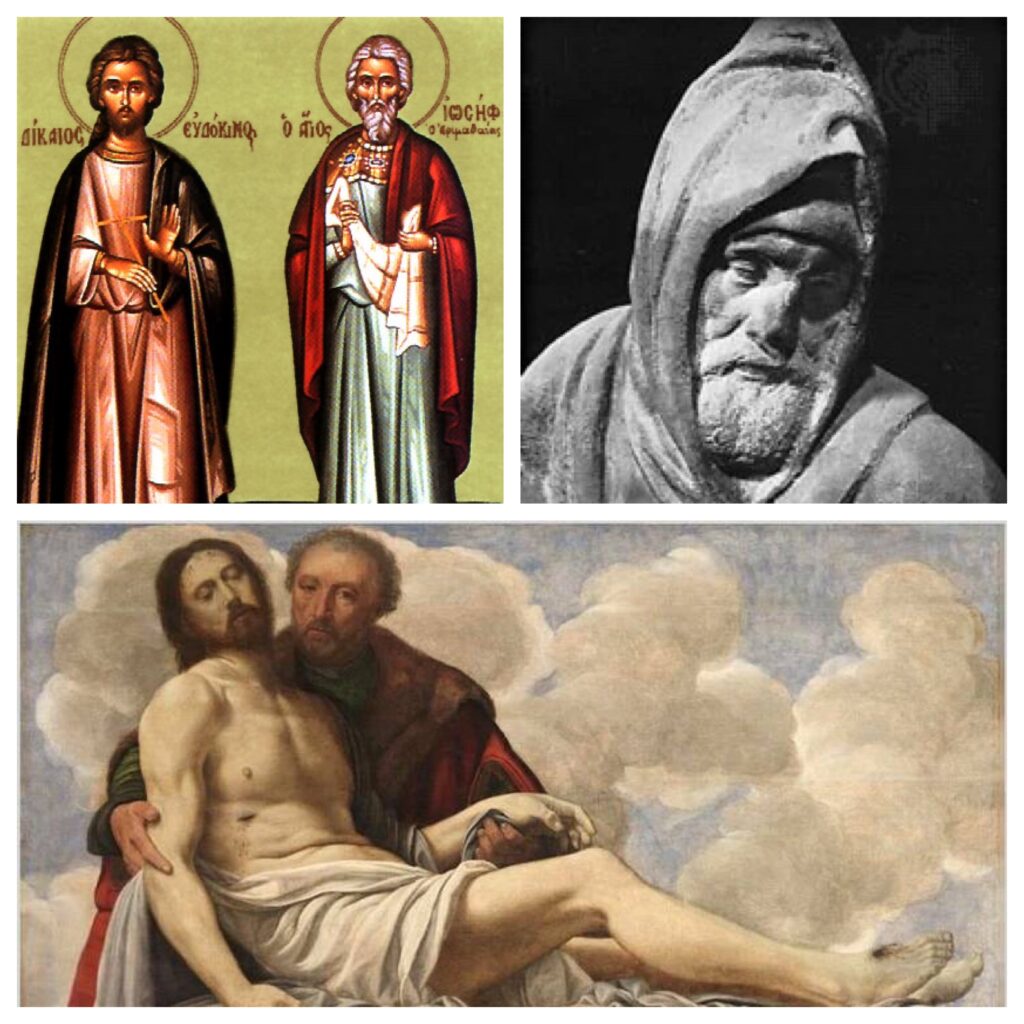

In the Uniting Church’s resource provided for worship leaders, Uniting in Worship, there is a Calendar of Commemorations, based on the cycle of annual feast days for saints in the Anglican, Catholic, and Orthodox churches—but broadened out to be much wider than this. Many days of the year are designated to remember specific people. Today is the day to remember Joseph of Arimathea—a figure best known for the scene, reported by all four Gospels, when he takes the body of Jesus from the cross and places it in a tomb.

Joseph was a common biblical name—son of Isaac, father of Jesus, amongst others. This Joseph is distinguished by his home town, Arimathea. All we know is that it was a town in Judea (Luke 23:51). It is thought it may be Ramathaim Sophim, the birthplace of Samuel (1 Sam 1:1, 19), which appears in the LXX as Greek Armathaim Sipha.

In the earliest Gospel, this Joseph is described as being both “a respected member of the council” and as one who was “waiting expectantly for the kingdom of God” (Mark 15:43). The kingdom of God is what Jesus was preaching, according to Mark (1:15; 4:11) and that is what the crowd lining the streets into Jerusalem understood him to be bringing (11:10). Mark’s report indicates that Joseph, who shares this expectation with Jesus, “bought a linen cloth, and taking down the body, wrapped it in the linen cloth, and laid it in a tomb that had been hewn out of the rock; he then rolled a stone against the door of the tomb” (Mark 15:46).

Matthew reworks this description; he is “a rich man” (rather than a member of the council) who was “a disciple of Jesus” (Matt 27:57). By contrast, Luke introduces Joseph as “a good and righteous man” (Luke 23:50), echoing the much earlier descriptions of Elizabeth and Zechariah (1:6) and Simeon (2:25).

Luke explains that Joseph, “though a member of the council, had not agreed to their plan and action” (Luke 23:50–51). Differentiating Joseph from the others in the council seems important for Luke; after all, in Luke’s account, the council had brought Jesus to Pilate, saying that “we found this man perverting our nation, forbidding us to pay taxes to the emperor, and saying that he himself is the Messiah, a king” (23:2).

When Pilate demurs, council members press the point: “he stirs up the people by teaching throughout all Judea, from Galilee where he began even to this place” (23:5). After sending Jesus to Herod (a curiously unhistorical action, given the actual governance arrangements at the time), Pilate states his belief, for a second time, that Jesus is innocent (23:4, 14), before the “the chief priests, the leaders, and the people” together agitate for the release of Barabbas (23:13, 18). Luke’s more detailed description of Joseph places him at odds with this whole sequence of events; “though a member of the council, had not agreed to their plan and action” (23:50–51).

Luke further indicates that Joseph “was waiting expectantly for the kingdom of God” (23:51), picking up on Mark’s description. In the context of Luke’s two volumes, however, this description aligns Joseph very closely with the enterprise that Jesus was engaged in; “I must proclaim the good news of the kingdom of God to the other cities also; for I was sent for this purpose”, Jesus declares (4:43); “he went on through cities and villages, proclaiming and bringing the good news of the kingdom of God” (8:1).

Jesus sends out both the twelve, and then the seventy, to proclaim the kingdom of God (9:1–2; 10:1, 9–11); he instructs his followers to pray, “your kingdom come” (11:2) and to “strive for [God’s] kingdom” (12:31); he tells. parables of the kingdom (8:10; 13:18, 20); and teaches that “the kingdom of God is among you” (17:20–21).

As Jesus draws near to Jerusalem, those travelling with him “supposed that the kingdom of God was to appear immediately” (19:11); indeed, as he enters the city, people acclaim him as “the king who comes in the name of the Lord” (19:38). At the last meal he shares with his disciples, Jesus looks to the fulfilment of the kingdom (22:14–18, 28–30), and one crucified alongside Jesus shares this hope, saying to him, “Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom” (23:42).

Jesus continues this after his death and resurrection, “appearing to them during forty days and speaking about the kingdom of God” (Acts 1:3); subsequently, key followers of Jesus proclaim the kingdom in key locations— Phillip in Samaria (8:12), Paul and Barnabas in Antioch (14:22), and Paul in Ephesus, (19:8). This was Paul’s common activity everywhere (20:25); the final picture of Paul is that he lived under house arrest in a Rome, “proclaiming the kingdom of God and teaching about the Lord Jesus Christ with all boldness and without hindrance” (28:31).

So Joseph, “waiting expectantly for the kingdom of God” (Luke 23:51), is firmly aligned with Jesus and with his followers in Luke’s Gospel. He is clearly, as Matthew reports, “a disciple of Jesus” (Matt 27:57).

In the fourth Gospel, Joseph performs the same task, requesting the body of Jesus from Pilate, and securing a safe place as the resting place for the body. He does this in conjunction with Nicodemus, “who had at first come to Jesus by night” (John 19:39). We first meet Nicodemus earlier in John’s narrative (3:1–21); at this time, he engages in what might be characterised as an appreciative enquiry with Jesus, under the cover of night (3:2), presumably so that he didn’t “out” his interest in what Jesus was teaching. It’s perhaps worth noting that Jesus spoke about “the kingdom of God” in his conversation with Nicodemus (3:3, 5)—the very same phrase that is key to the preaching of Jesus in Mark and Luke.

Some chapters later in John’s narrative, as Jesus experiences intensified opposition whilst in Jerusalem for the Festival of Booths (7:1–13), and the Pharisees and temple authorities join forces to send the temple police to arrest him (7:32), Nicodemus appears once more. The temple police return the temple, saying that they will not arrest him (7:45–46).

Nicodemus steps in; he is introduced as the one who “had gone to Jesus before, and who was one of them”—that is to say, one of the disciples (7:50). He speaks boldly: “our law does not judge people without first giving them a hearing to find out what they are doing, does it?” (7:51). The dismissive reply of the Pharisees further aligns him with Jesus; “surely you are not also from Galilee, are you?” is their rejoinder (7:52). His allegiance is clear, at least in the minds of the Pharisees, if not also the narrator of the Gospel.

Nicodemus returns a third time, after the death of Jesus, when the body of Jesus is requested by Joseph of Arimathaea, who is here,clearly identified as being “a disciple of Jesus, but secretly, for fear of the Jews” (19:38).

Joseph of Arimathea is here described as being “a disciple of Jesus, but secretly, for fear of the Judean authorities” (19:38). The fear of the Judean authorities has been a recurrent motif in John’s narrative (5:1; 7:13; 9:22; here, and 20:19). (The term I translate as “Judean authorities” is most commonly rendered as “Jews”, but this translation is too wide and does not accurately reflect the way the term is used in John’s Gospel.)

Once again, Joseph is identified as a disciple of Jesus (John 19:38; so also Matt 27:57, and, as we have argued above, that is the implication in both Mark 15 and Luke 23). Both Joseph and Nicodemus, we might presume, were numbered among the “many, even of the authorities, [who] believed in him”, but who, “because of the Pharisees, did not confess it, for fear that they would be put out of the synagogue” (12:42).

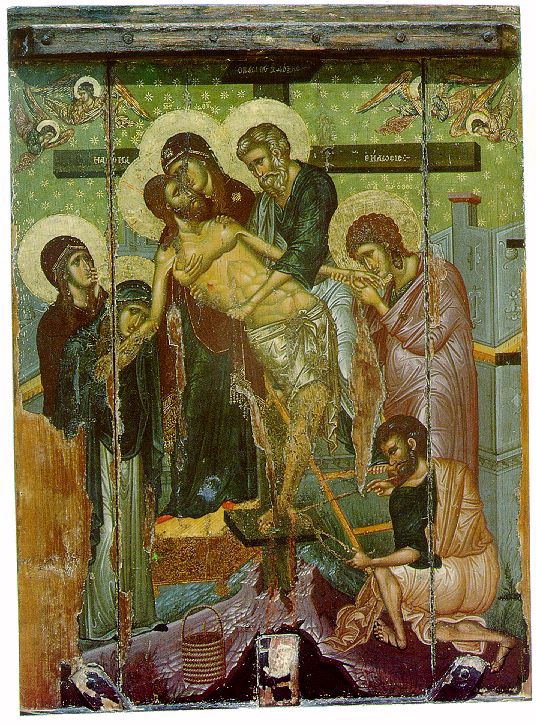

The manner in which the body of Jesus is removed from the cross into the grave, anointed with an extravagantly large amount of spices, myrrh and aloes and wrapped in linen cloths “according to the burial custom of the Jews”, and placed in a previously unused tomb (19:38–40), reflects the tender, respectful approach of these two of Jesus’s disciples.

The body of a crucified person would normally be thrown into a communal grave outside the city; all four Gospels take pains to report that this as not the fate of Jesus. The historicity of this claim must surely, however, be significantly doubted. The point of the narrative is not historical verification. The intention is to continue to attest to the significance of Jesus, acknowledged as king, given exactly the kind of extravagant funerary rites that were befitting for a king.

And that is the gift that Joseph of Arimathea offers to followers of a Jesus, even to this day: a compassionate, respectful treatment of the body of Jesus. It’s good to remember him for this, today.

Rev. Dr John Squires is Presbytery Minister (Wellbeing) for Canberra Region Presbytery and the Editor of With Love to the World. This reflection originally appeared on his blog, An Informed Faith.