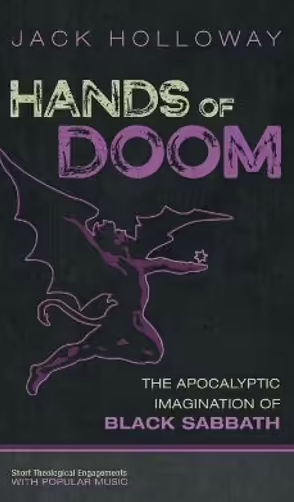

Reviews: Hands of Doom: The Apocalyptic Imagination of Black Sabbath by Jack Holloway & Bodies: Life and Death in Music by Ian Winwood

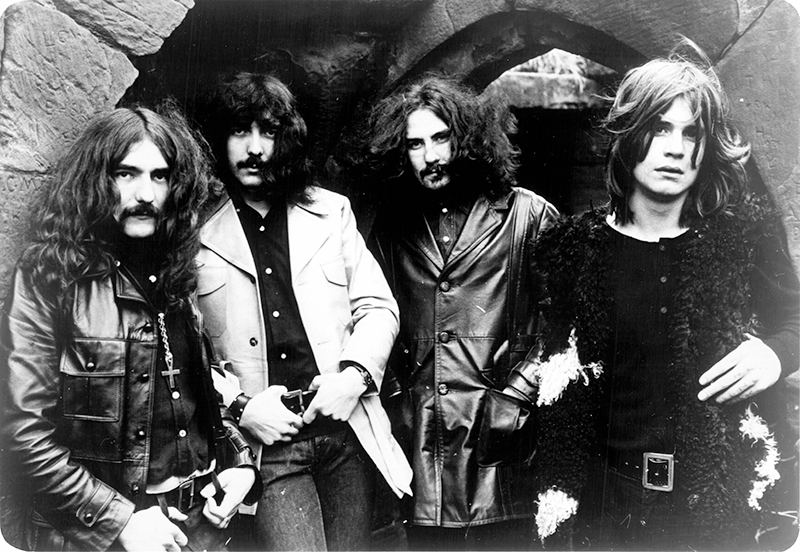

I never thought I would be reviewing a book extolling the theological virtues of Black Sabbath. They have a reputation as pioneers of doom metal, fronted by the so-called Prince of Darkness, Ozzy Osbourne, using all the tropes of metal that would later become cliché: fascinated by death, destruction, drugs and the occult.

Wisely focussing on the first few Black Sabbath albums produced in the early 1970s (before they became something of a parody of all things metal), Jack Holloway sees realism and a surprising moral streak in their music. Unlike Led Zeppelin, whose interest in the occult seemed simply part of their overall hedonism, Holloway sees Black Sabbath speaking truth to power, singing prophetically about hell on earth, in the age of Nixon, the Cold War and the Vietnam War.

Lyricist Geezer Butler compared meetings of generals and politicians to black masses. The song ‘Children of the Grave’ is about the threat of nuclear war, a theme that pops up again in Osbourne’s solo music. Coming from a working-class background, Butler additionally noted that it is the poor who always do the frontline fighting.

Holloway says Osbourne’s voice is hardly ‘pleasant’ but expresses despair at violence and hypocrisy, becoming closer to blues and protest songs than those of the heavy metal bands who would follow Black Sabbath and sound superficially like them. The songs become songs of lament, in the Old Testament fashion, with medieval hell being symbolic of a worldly hell. Failure to acknowledge pain around us is denial, says Holloway, and is unbiblical, ungodly and untruthful.

More than this, Holloway sees in the band a continuation of the tradition of biblical prophecy. Forgiveness is vital, but the Bible also contains vehement and righteous denunciation of powerful wrongdoers. There is confrontation with the realities of the world and calls for justice. The Old Testament prophets, like Black Sabbath, may have been gloomy, but confronted the real world, unlike, says Holloway, hippie culture and some elements of evangelical Christianity, which seek escapism – in the latter case, avoiding confrontation with inequality and offering instead only the balm of the afterlife. Black Sabbath may have been critical of the church (Butler is a lapsed Catholic) but this may be fair enough if we are thinking of failures to advocate for the marginalised or the sad reality of clerical scandals.

The band were often labelled Satanist but their relationship to the Satanic is more complicated than it might seem. Apparently, a group of proper Satanists who were hanging around the band decided Black Sabbath weren’t really Satanist but were just using Satanist imagery as theatre, and grumpily put a curse on them. Holloway sees Black Sabbath’s use of the figure of Satan in their lyrics as closer to the Old Testament version of the accuser, a kind of prosecuting attorney, rather than the later, medieval hoofs-and-horns Lucifer character. In the song ‘Lord of this World’ they recognise, rather than celebrate, the Devil as symbolic of the presence of evil, and its dominance, in the world, further asking ironically if those with ‘greed and pride’ would hypocritically turn to God when faced with their own mortality. Holloway links this to St Paul, making the case that Paul’s reference to the ‘Lord of this world’ is to Caesar – to those with worldly power who abuse it for their own ends.

In contrast, and astonishingly, in a song such as ‘Almost Forever’ (from their third album) there is an almost evangelical recognition of the need for repentance and rescue, with Osbourne, through Butler’s lyrics, chastising those who fall in with the wrong crowd and deny God, and singing, ‘God is the only way to love’. And Butler recognised Jesus’ role as prophet and defender of the poor. ‘Iron Man’ is supposedly about Christ.

On the other hand, Osbourne certainly exploited his wild reputation. Ian Winwood, a rock journalist, describes Osbourne sitting in the garden of his rural mansion, drooling and bragging about how easily he can procure drugs. Osbourne is notorious for drunken misdemeanours, and was, more seriously, once arrested for attempting to murder his wife. He was so drunk he couldn’t remember the incident. Holloway is not wholly uncritical, either, criticising Black Sabbath’s appropriation of Black blues culture and rock’s often glaring sexism, of which Black Sabbath are not innocent.

Winwood’s book Bodies is largely about how drugs and alcohol have laid waste, and continue to lay waste, to rock musicians. Perhaps in contrast to the outside image of glamour, he presents a sad parade of drunks and addicts travelling on tour buses, throwing money and health away. Winwood also describes his own decline into addiction. Guilty, he says, of profiting from writing about debauchery – it makes for good headlines – there may be a bit too much detail here, both about others and himself. He certainly has the gift of the gab, and the language and stories here are not for the faint-hearted.

He writes about how prolific drug and alcohol use and abuse (and much more besides) becomes normalised. Rock stars become legends for excesses that nearly kill them (see Motley Crue), and sometimes do. If they are not lionised for their outrageous behaviour, it still becomes entertainment. Winwood has plenty of examples. He describes one horrifying and sickening case of a singer he knew declining into crystal meth addiction, criminal activity and prison. Further, ‘the music business attracts people hardwired for self-destruction,’ writes Winwood. Deaths from substance abuse and suicide are more common in rock musicians.

Of course, musicians can’t dodge blame, but Winwood criticises a music industry that has profited from the image of hedonism, and that has taken little responsibility for the mental health of its charges. And ‘charges’ may be the right word, as rock musicians have typically been young, naïve, bamboozled and dazzled by sudden fame, wealth and access to drugs, access that record companies rarely curbed and mostly facilitated. Metallica – nicknamed ‘Alcoholica’ by themselves – went from teenagers to selling tens of millions of copies of albums, with no exposure to normal life, a license to do whatever they wanted, and a predictable toll on their bodies and personalities, and their record company capitalised on the band’s destructive image.

Often recognition comes too late. Jack Holloway describes how Black Sabbath, while abusing drugs themselves, were also aware of the pitfalls, and wrote about it in their songs. Winwood describes Lemmy, lead singer of Motorhead, despite having an amphetamine habit, as being ‘moral’ about drugs. He said (as if it were a revelation) that people are ‘better off’ without drugs. More interestingly, he lambasted the likes of Keith Richards and Lou Reed for glorifying drug taking and influencing other musicians to become heroin users. Winwood is sentient enough to, amongst all the other downsides, realise that his own drug use played a small part in fuelling horror and misery in the South American drug scene.

Winwood begins by writing that the rock industry is ‘systematically broken’, but two-thirds of the way through the book he decides that self-destructive lifestyles are ‘part of the fabric’. Is rock’n’roll extricable from ‘sex, drugs and rock’n’roll’? There remains a disjuncture between recognition of the music industry as an industry, with the responsibilities that entails, and a glamourisation of the rock lifestyle. Part of the problem is that rebellion and a ‘perpetual adolescence’ (as Winwood calls it) are built in. You don’t get quite the same attitude in, say, jazz or folk. A youthful honesty and idealism can be good, but in rock there is too much focus on staying young, which becomes a bit embarrassing in older rock stars and can simply mean a prolonged lack of wisdom. Rebellion can be good too, if, like Black Sabbath, you are questioning entrenched inequalities. But it can too easily become inward-looking indulgence, with destructive consequences.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.

1 thought on “Is the rock industry to blame?”

It was pretty amazing to see Ozzy and Tony Iommi close out the Birmingham Commonwealth Games with the intro to Iron Man followed by Paranoid, as among the most famous sons of their home town. These are iconic songs in modern culture. The irony in this article of a band named after the Satanic Mass having a moral message in their lyrics is quite challenging, especially in view of the appalling example they set of hedonistic lifestyles. Black Sabbath represent the deep confusion in metal culture, responding to the failure of Christianity to present a coherent moral vision.