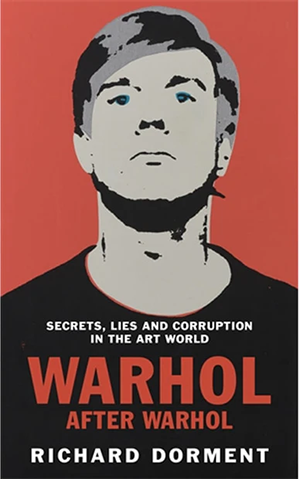

Review: Warhol after Warhol, Richard Dorment, Picador

The relationship of art to the artist and what constitutes high art are issues that became key in the work of Andy Warhol, and that sit, ironically – or appropriately – at the centre of a lawsuit that is the subject of this art-fraud thriller, which also highlights the greed and subterfuge of the art world centred in New York.

In the early 2000s a movie producer, Joe Simon, submitted two Andy Warhol paintings he was planning to sell, a small collage and a Warhol self-portrait, to the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board in New York. The board, without giving any reasons, denied authenticity and stamped the canvases ‘denied’, defacing them. There was, as it turns out, clear evidence that the collage was fake, but the self-portrait, part of a series of silkscreen prints, was more contentious.

Author Richard Dorment, an art historian and critic, was contacted by Simon, who asked for help. Dorment demurred that he was not an expert on Warhol, but he became enthralled in the case, and eventually did his own research which led to a series of articles in the New York Review of Books that were increasingly critical of the secretive board, which was linked to the Andy Warhol Foundation, and which Dorment began to suspect was up to some shady dealings in order to boost the coffers of the foundation, and the wealth of the foundation’s executors. Dorment is not an investigative journalist, he apologises, but his book reads like the work of one.

Jed Perl wrote recently in the New York Review of Books about how Warhol has become more significant than Picasso because of the move from artistic appreciation of genius to a more ironic consideration of the art world and what art is. Warhol, originally a commercial artist, brought notions of mass-produced art to high art, both in his subject matter – soup cans and movie stars – and his increasingly ‘hands-off’ methods, which included simply directing printers to make his canvasses. He liked this process as it created space for mistakes and surprises, and in not showing obvious signs of being from his own hand, exemplified Warhol’s Duchampian attitudes to what could be considered high art. Warhol later in his career was telling people he didn’t paint his own paintings.

This, in turn, makes deciding on what are authentic works difficult. The fact that the foundation, formed after his death from his assets, was worth a billion dollars in 2010 made the stakes very high.

Simon’s Red Self-Portrait was printed at Warhol’s behest, but away from his celebrated Factory studio. Although signed, the board decided it wasn’t Warhol’s own work. Simon took the board to court, in order to prove that his painting was legitimate. Other owners of similar works came forward to either support Simon’s case or complain about the authentication board’s authoritarian attitude.

Dorment argues that what emerged was that the board, in a conflict of interest, had financial motives for not only denying the authenticity of Simon’s painting, but authenticating paintings they had confiscated as fakes which the board subsequently sold as legitimate. Dorment argues that the foundation, through the board, effectively authenticated works when it suited them, i.e. when they had these works in their collection.

The court case is a tale of shark-toothed lawyers, pop stars and a murdered Russian oligarch. In Dorment’s meticulous account he, Simon and others undoubtedly were the wronged party. But it also begins to sound like very rich people fighting over overpriced art. There is some irony in this, considering the art was made by an artist who was so ambiguous about the idea of authenticity, yet obsessed with money. One wonders what Warhol would think of it all.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.