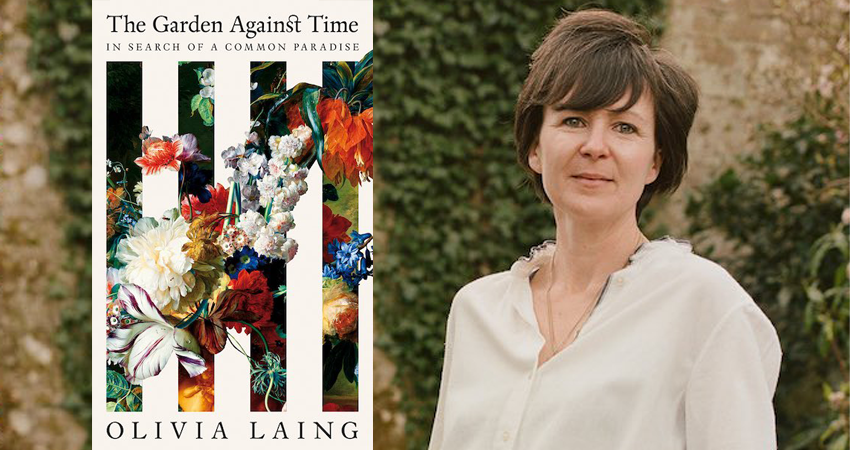

Review: The Garden Against Time, Olivia Laing, Picador

Olivia Laing and her husband, the poet Ian Patterson, bought a gorgeous, traditional English house and garden in East Anglia during the Covid pandemic. Originally the house was owned by a famous nurseryman, Mark Rumary. During lockdowns Laing carefully restored and updated the long-neglected garden, heading to a self-imposed deadline of an open garden day. She sets off in the morning with tools, pulling dead climbers off walls, digging out roots with ‘sweating and swearing’, nursing the sick, chasing out bullying weeds and directing builders as they trample beds and lay paving stones.

Laing, as well as being a writer of note, studied herbalism, and she knows a lot about plants, as well as about the history of gardens. Her restoration of the garden is exquisite, without being pristine. (An article on the garden in the UK’s House & Garden magazine can be seen here.) It’s hard to not be a little envious of her little slice of paradise. Her bourgeois idyll seems almost indulgent in times like these, but Laing is not unaware of this, and her book is about what it means to grow a garden during times of political or personal unrest, taking inspiration from artist-gardeners of the past.

There is the issue of inequality, when the kind of home she has is obviously not available to everyone, when not everyone has access to shaded and perfumed land to retreat to. Her book is about what it means to cultivate, encourage, enjoy, and how selfish this is, or not – how it may be a ‘desperate’ resistance against the negativity of the world, a little act of defiance that promotes peace and beauty and patience and keeps us sane. She writes that her garden helped her to look at time differently than in the 24-hour news cycle.

In the UK, one per cent of the population own fifty per cent of the land, a legacy of enclosures in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. That slim percentage, Laing writes, is represented visually in the paintings of the likes of Claude Lorrain and in the vast remodelling of country estates by the likes of Capability Brown. As naturalistic as these were meant to be, both featured a lack of people, particularly the folk who had been working the common land or using its resources. A further link between gardens and inequality is also the fact that some of the largest country estates were funded from the profits of slavery.

During the English Civil War, the Diggers, one of the more radical sects, rebelled against gardens as areas of privilege, and created common vegetable gardens in London. For their impudence, they were beaten up, driven off, their gardens destroyed. At the same time, another radical, John Milton, was writing about exile and gardens in his Paradise Lost, which Laing reads in between discoveries and mulching and trundling wheelbarrows. The Persian word ‘paradise’ means garden, and there is surprising detail in Milton about cultivation of garden plants. It seems that even in his mind, Milton was envisaging the act of gardening as an alternative to tumultuous times.

The poet John Clare, too, suffered from the enclosure of public landscapes, but for him the economic desolation came second to the ecological one. For Clare, enclosure created a loss of familiarity and sense of place. Clare felt a loss of a paradise where his relationship to plants had been intimate, a loss that drove him mad, in the end. From his asylum, he would write agonised letters asking after the health of any number of garden plants. The stories of Milton, the Diggers, Clare and Cedric Morris, who created a utopian artists’ enclave as a refuge from homophobia and mechanisation in the mid-twentieth century, resonate with Laing who, in her youth, participated in protests and experiments in utopian communal living, at one point living up a tree, if I recall correctly. She writes about how the polymath artist William Morris envisaged a garden as, in contrast to Capability Brown, an intimate, domestic space where appreciation not mastery is the overriding philosophy, and where art, nature and equality are inextricable.

Anyone familiar with Laing’s other books will know about her interest in the filmmaker Derek Jarman, who died of Aids and who spent his last years in a cottage on a shingle beach in the south-east of England, creating a remarkable, salt-and-other-hardships-tolerant garden. This garden, which inspires Laing in its unplanned, accumulated nature, was a refuge from Aids and homophobia, and also a refuge from a tough childhood. There is an easy symbolic connection to be made in the flowers growing from harsh shingle beach and artists like Jarman helping art to flower against the aridity of the world.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.