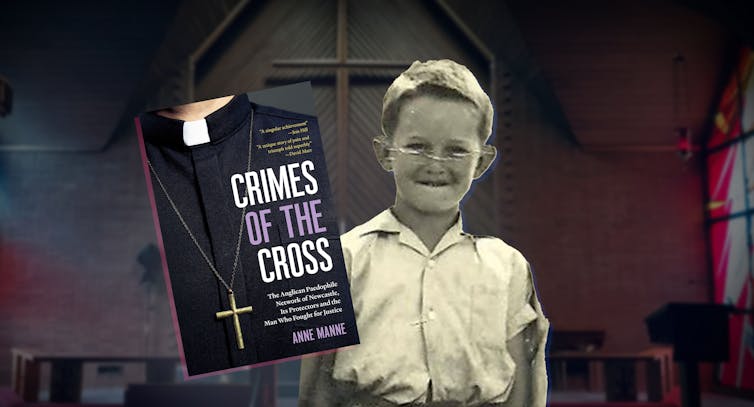

In 2017, the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse found that within the Anglican Diocese of Newcastle, priests had perpetuated crimes of abuse for at least 30 years. Serious allegations were mismanaged, misplaced or ignored. Crimes were minimised. “Abusive and predatory” behaviour was wrongly portrayed as “consensual”.

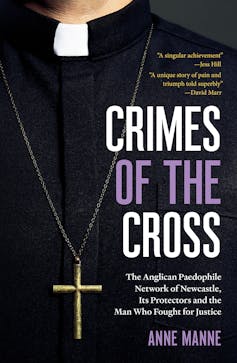

In her new book, Crimes of the Cross, journalist Anne Manne provides an intricate and compelling account of how multiple diocesan clergy and leaders covered up allegations, protected priests who were known perpetrators and failed to care for survivors.

Manne builds on the groundbreaking work of Newcastle Herald journalist Joanne McCarthy, whose investigations, starting in 2006, led to the establishment of the 2012 royal commission. Manne’s writing is informed by a variety of source materials, including interviews with McCarthy and various survivors, and evidence from the royal commission.

On the first page, Manne warns us this story is about a “sinister paedophile ring of priests demonic in their cruelty”, supported by “a ‘grey network’ of protectors”. These protectors – clergy and lay people – staffed helplines, were on professional standards committees, mismanaged or ignored complaints, and never reported criminal activity to police.

At least six priests associated with the diocese and one lay reader have been convicted of child sex offending. Other priests were identified as “prolific” abusers, but not convicted in their lifetime.

Crimes of the Cross centres the stories of survivors. Their testimonies are retold with sensitivity, although explicit and distressing detail is provided at times (including in the opening pages).

Manne’s work concentrates primarily on one survivor – Steven Smith – who, from the age of ten, was repeatedly abused by a priest, Father George Parker. This happened over five years, from 1971 to 1975 – the year Parker was transferred to nearby Gateshead, where the abuse (initially) continued.

The 1971 arrival of Parker, then aged 30, is presented as a disruption to Smith’s happy and carefree childhood. Smith told Manne his childhood summers were spent in Bush Creek, “fishing and swimming”.

Despite this, Smith told Manne his parents’ marital problems made his family vulnerable. Their life revolved around the church community. At first, Smith felt proud of Parker’s attention to him.

However, when he became an altar boy, “everything changed” and the abuse started. Assaults happened at church, in the car with Parker, driving between churches, when his mother sent him to visit the rectory, and when Parker would pull him out of school, no questions asked. Smith said he was abused “fortnightly”; he was raped “hundreds of times”. His abuse, he said, was a “kind of kidnapping”.

Manne writes:

a psychologist’s report years later stated that Steve had gone through one of the most extreme cases of sexual abuse that she had ever encountered.

Through Smith’s and other stories, Manne explores how criminals such as Parker hid behind a “mask” of priesthood, and perpetrated crimes that significantly harmed the lives of those they targeted. She shows the human cost of bad policy and delayed justice.

Smith’s personal story of surviving abuse and campaigning for justice is at the centre of the book, which is divided into five chronological parts.

Shame and fear of social isolation can prevent a survivor from disclosing abuse. “Steve was a bright spark of a kid who saw with sharp clarity the social world around him,” Manne writes.

“He knew the consequences for his mother and family should the situation be made public – shame, expulsion from the church, ostracism from the community.”

While Steve did tell his mother about the abuse in 1975 (on the way home from Gateshead), he would not report it to police until February 2000.

In the 1990s, Smith disclosed to an Anglican helpline – where he spoke to a priest, Graeme Lawrence, who would later be convicted of sexually assaulting a 15-year-old boy in 1991.

In 2000, Smith reported Parker to the police. A trial against Parker was held in 2001, but when the defence team presented an alibi for him, the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions withdrew the charges. In late 2016, the charges were reinstated. The trial was delayed as Smith gave evidence at the royal commission. Parker died in January 2017, before facing court.

Seeking justice

The second section, Team Church, describes a missed opportunity for justice. After Smith made the police report, Parker was charged and a trial was set for August 2001.

Manne recounts how diocesan staff made efforts to withhold information. For instance, staff, including Lawrence, had “exact records” of when and where clergy had been employed, as it was contained in parish yearbooks.

However, Manne notes when the detective working on the case asked for information about when Parker had been at Gateshead church, “no one in the Anglican Church told him of the existence of these records”. As as result, the detective “was preparing to frame the charges for 1974 – the wrong year”.

The case was no-billed and would not be reopened until after the royal commission.

Manne also shows how the diocese failed to provide pastoral care. Sadly, this is not uncommon in cases of abuse in church communities.

In fact, Manne suggests the well-documented failings of Catholic leaders may have worked to obscure what was happening in the Anglican diocese.

Newcastle journalist Joanne McCarthy – who was instrumental in reporting instances of abuse within Catholicism – told Manne she didn’t initially understand “how bad child sexual abuse was in the Anglican church”.

In 2016, Manne herself had been trying to get at the “inner workings of the secret, mysterious Catholic committees” who were “responsible for cover ups” when she heard about the public hearings investigating the Anglican Diocese of Newcastle.

Within the diocese, staff appeared more interested in protecting the institution than responding to survivors. Some refused to hand parish records to police. Legal representatives used aspects of Steve’s history – not disclosing to his own father, being diagnosed with mental illnesses – against him. Manne astutely notes:

It is common for survivors of child sexual abuse to suffer anxiety, depression and PTSD. Steve’s admission to a psychiatric hospital could have been interpreted as evidence he had been sexually abused. Instead, it was used to undermine his credibility. He was “mad”, it was implied, his testimony unreliable and not to be believed.

Manne suggests while Steve was “denigrated in court”, there was “a reservoir of trust and goodwill towards the church”. But this reservoir was not limitless.

Towards the end of this section, Manne’s attention shifts to the mishandling of allegations in the Anglican Diocese of Brisbane. This points to the reality that both abuse and inadequate institutional responses have been widespread.

Denying what ‘ostensibly good men’ do

While Steve’s experiences propel the book, Manne’s lens is wider. She considers how successive diocesan leaders and staff continued to mismanage complaints and to direct sympathy towards the abusing priests and the institution, rather than the many victim-survivors.

This allows Manne to clearly show the abuse perpetrated by priests was not isolated, nor random events committed by one “bad” man (or even a few bad men). Rather, there was a network of abusers and enablers, as well as systemic failures that allowed the church to become a “cover” for criminal activity. At the centre of the story, Manne states, there is “the denial of what ‘ostensibly good men’ do”.

A pivotal chapter, titled “The Wolf Hiding in Plain Sight”, uncovers the criminal activities of one of these “ostensibly good” men.

In late 2009, Manne tells us, Lawrence – by now the dean of the cathedral – was reported for sexual misconduct with an underage boy (in the early 1980s) to Michael Elliot, an ex-policeman who had been hired by the diocese to deal with sexual abuse complaints.

Lawrence, a powerful, controlling figure, had shaped diocesan culture and “groomed a whole city” for decades. Manne explains:

By grooming, a paedophile creates compliant, trusting people who simply won’t believe accusations of sexual misconduct. Presenting oneself as a very caring priest establishes the “halo effect”, a reservoir of admiration and goodwill, whereby people see the abuser as beyond reproach, enabling them to hide in plain sight. Grooming creates a network of defenders who can be mobilised when needed.

In Lawrence’s case, this mobilisation resulted in pushback against Brian Farran – the then Bishop of Newcastle – after Lawrence was defrocked in 2012 due to the sexual abuse allegations against him.

Lawrence’s supporters saw the professional standards unit, which Elliot headed, as troublemakers. Smith and Elliot received death threats, Elliot’s car and home were “repeatedly vandalised”, and his dog went missing.

Manne writes:

If you thought you were dealing with a Christian community, the death threats and intimidation, the vandalism of cars and homes, seems completely shocking. But if you reframed and realised that hidden within the church was a paedophile ring – then it became unsurprising.

Throughout, Manne demonstrates that abuse of power was a key element in the decades of criminal activity within the diocese. At the same time, recognition of survivors was slow. “For many in the church, it was easier to preserve good memories and dismiss survivors as liars.”

Why weren’t survivors believed?

The final section of the book asks important questions. Why was the abuse covered up? Why weren’t children believed? Manne’s analysis is both insightful and chilling. She reflects:

The desires of the paedophiles were heinous but simple. The cover-ups by the church hierarchy were dreadful, but you could see the logic: the protection of reputation, avoidance of scandal, fear of losing their income, houses and careers should they turn whistleblower. But the laity – what did [they] get out of it?

Why were everyday churchgoers invested in protecting the institution?

Stepping into Newcastle Cathedral, Manne finds an answer. She imagines “the tall figure of Dean Graeme Lawrence sweeping along in his white lace and gold brocade robes, and how, amid this grandeur, a congregation might feel close to God”.

So much of this story, she writes, is about “status and the pursuit of social significance”. People were invested in their image of Lawrence, she concludes. Supporting powerful figures within the church gave regular parishioners a place and purpose.

And that, she presumes, was what Lawrence wanted: “There was no better way to groom a child, their family, and community than by using the altruistic mask of a priest.”

To point out the hypocrisy and systemic failings nested within the diocese, Manne turns to the Christian parable of the Good Samaritan, which tells “the story of a person who was attacked, robbed and left half dead on the side of the road”.

In the story, two religious leaders ignore the man, while a social outsider (a Samaritan) stops, sees the injured man and provides care. Manne compares abuse survivors to the person lying beaten on the side of the road, and accuses many clergy and lay people of having “averted their eyes”, just as the leaders in the parable did.

Some, she writes:

were so focused on gaining social significance, on clawing their way up the church hierarchy, that they forgot the radical egalitarianism at the heart of the teaching of Jesus. They forgot especially what Jesus told the disciples about children.

Manne’s reading of the situation breaks my heart, but perhaps that’s the point.

As she draws her book together, she writes:

For some in the church there was a complete failure of moral imagination – an inability or refusal to acknowledge the soul murder of abuse victims. Why this blindness? The answer is terrible. Because the victims were children

In the balance of power, everything was in the favour of powerful men like Lawrence and Parker. Children, who had nothing, were silenced, ignored and shamed.

Go on fighting

Manne closes her book with a somewhat positive take: “Steve never stopped being a fighter.” She gives Smith the final words:

If something is wrong, it’s wrong. You have just got to go on fighting. Don’t ever give up.

As I reached the final pages, I was drained. I cannot begin to fathom the energy survivors such as Smith had to summon to go on fighting – in some cases for 20, 30, 40 years. Over lifetimes.

Manne’s book is certainly an emotionally difficult read, but it is also incredibly important. She highlights the lasting personal and social consequences of abuse, as well as woefully insufficient responses and victim-blaming cultures. She bears witness to the experience of survivors and to their fight for justice.

Yes, every churchgoer, every youth worker, everyone employed by a church – indeed everybody – should read this book. But read it with care (and perhaps with a friend) and pace yourselves: the story it tells is devastating.

If this article has raised issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone you know, call Lifeline on 13 11 14.

The National Sexual Assault, Family and Domestic Violence Counselling Line – 1800 RESPECT (1800 737 732) – is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week for any Australian who has experienced, or is at risk of, family and domestic violence and/or sexual assault.

Rosie Clare Shorter, Research fellow, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.