Reviews: Around the World in 80 Plants by Jonathan Drori & My Garden World by Monty Don

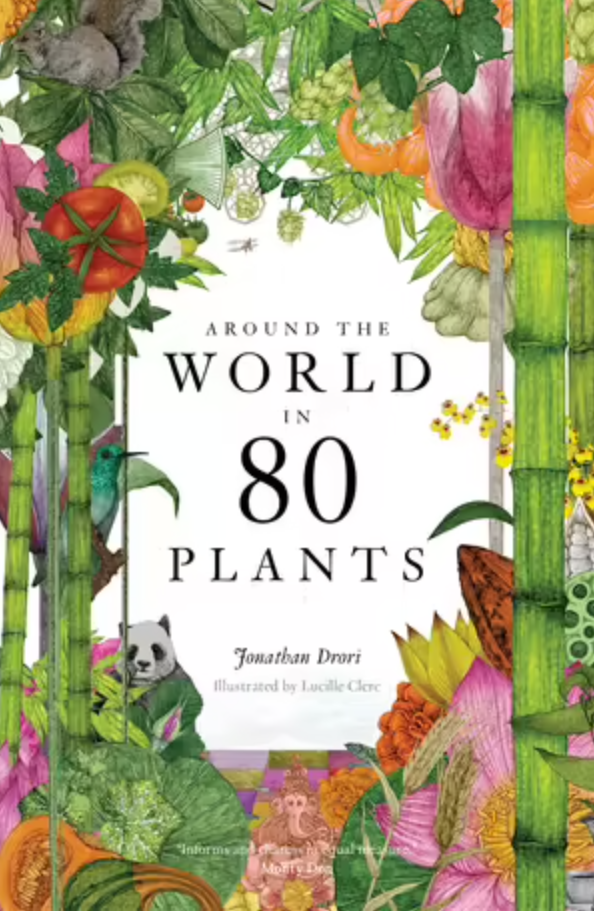

Writing last year about Jonathan Drori’s previous book, Around the World in 80 Trees, I suggested there were trees he could’ve included but didn’t and that perhaps he was working on a follow-up. Sure enough, here is Around the World in 80 Plants, and the brief is a little widened but with the same one- or two-page descriptions, and with intricate, delicate illustrations by Lucille Clerc.

As with 80 Trees, there are again plants he probably wishes he could’ve included (wheat, rice, mint?), and he says that if we are to manage to feed the world’s population we need biodiversity and must look beyond the 80 here. As it is, many of the plants that do make it into the 80 are significant for their use by humans, and some, such as the saffron crocus, now solely rely on propagation by humans to survive. It works both ways.

Unsurprisingly, the book is full of intriguing facts and etymologies. Nettles, which sting but also make good soup, like phosphate and so thrive where there is human waste and remains. Clover, in use as a rotational crop, drove European population increases in the 1750s. The name of the vegetable squash comes from a Native American word (not from their squishy properties). Nicotine takes its name from the Frenchman who introduced tobacco into France.

A surprising amount of the plants here are drugs – medicinal or so-called recreational – kava, cannabis, tobacco, poppies. Mexican yams are used to make asthma-controlling drugs. Mandrake roots, which have been historically associated with witches, contain a psychoactive substance and may be the reason witches were once associated with flying.

Other plants here are toxic, at least to humans, and, as with arums, often warn-off humans with a stench that is otherwise irresistible to insects. Licorice, which seems to attract extremes of affection and disgust, also has levels of toxicity, and if eaten every day for long periods can produce all manner of serious health problems.

Although the book is organised around individual species, Drori writes about connections, not just with humans, but also to each other, different species and to fungi, microorganisms and animals, highlighting the remarkable complexity of the plant world.

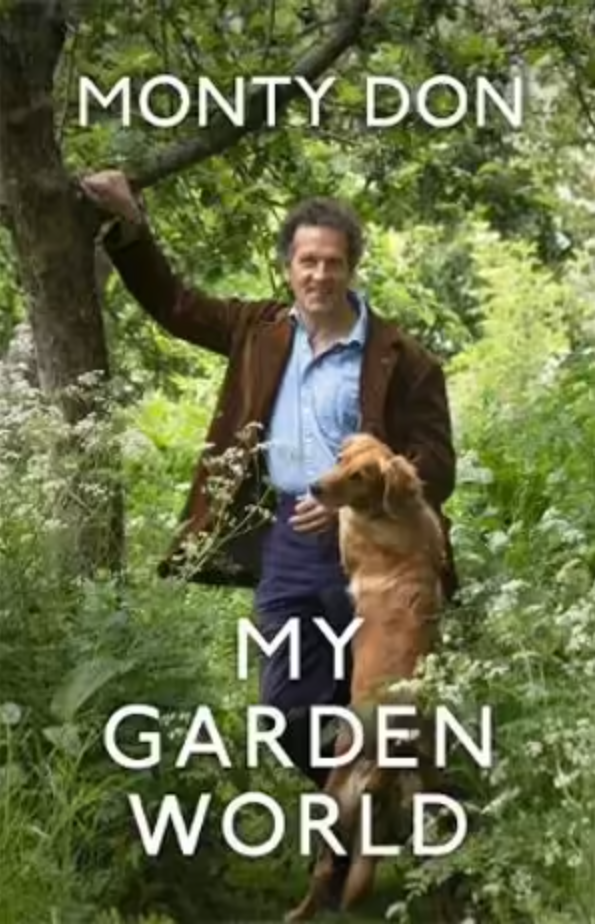

TV gardener Monty Don says he is not a ‘plantsman’, though there is lots about individual species of plants, as well as animals, in My Garden World, his diary of a year in his garden and farm. It’s not a guidebook, but from the first entry you are learning, even if the book is Brit-centric – that ‘magpie’ is a contraction of ‘Margaret Pie’, that the name ‘robin’ was not used until the twentieth century. In this he is not so much didactic as simply gently enthusiastic. He has that calm satisfaction of the keen gardener.

Don is known for his garden writing (and TV presentation), but he says he loves the wild countryside too, and he is a keen observer of its plants and animals and is careful of what he does in the garden to avoid disturbing its inhabitants. He is happy for some untidiness in the garden, if it helps the likes of hibernating frogs. Paul Bangay he is not. Neither is he a garden snob – he delights in the rare, but also likes the effect of mass plantings of common species such as the snowdrop.

On their own, the entries are like snapshots, but over-all they make a mosaic covering every corner of garden and field. And, he suggests, the act of noticing, in field and garden, helps us encourage and nurture wildlife, ultimately making the world a better place.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com