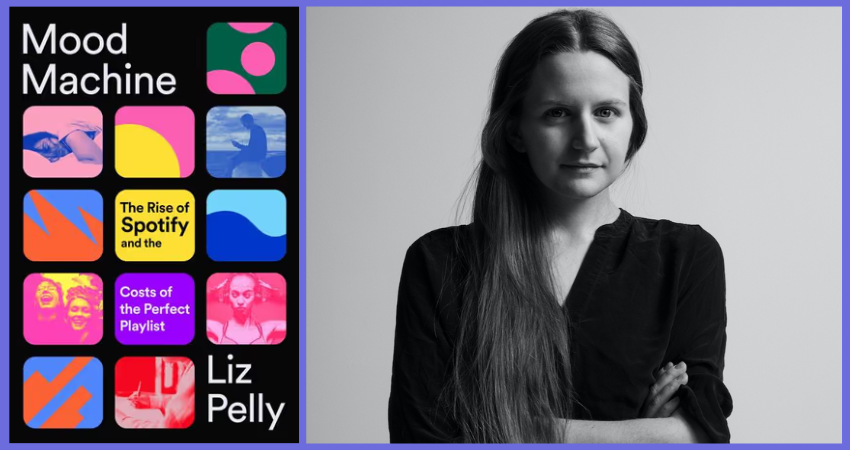

Review: Mood Machine: The Rise of Spotify and the Costs of the Perfect Playlist, Liz Pelly, Hodder & Stoughton

All the world’s music for low cost seems great for listeners, but that availability comes at a cost to artists, and listeners are being manipulated to increase the already-considerable wealth of Spotify’s founders. Liz Pelly, who is not a fan of Spotify, pulls no punches in her book, arguing that Spotify is part of a wider story of a ‘broken’ industry, and, we might add, the current online reality, where commerce is devaluing art.

Spotify’s founders, Daniel Ek and Martin Lorentzon, claimed they created Spotify, in a time of illegal file-sharing, to ‘save music’, but, counters Pelly, they had backgrounds in website building and ad technology and the evidence suggests they just wanted to make more money. They have stated that they were looking for ways to make ad money from file-sharing networks and happened to decide on music.

Initially, their idea was for a searchable music database, but then Spotify became a ‘curated’ service. Research soon suggested the majority of listeners wanted music based on context or ‘mood’ – relaxing, cleaning, exercising, partying, even sleeping. The game is to keep people listening, so Spotify plays on the self-absorbed idea that your life needs a ‘soundtrack’, and despite advertising about Spotify enabling you to discover new music, they don’t want you switching off, so the algorithms direct you to music you already know or music that is similar. This is very different to the (human) friend who might challenge you to broaden your artistic horizons.

The ’microgenre’ trend is just another way Spotify tries to personalise the listening experience, but for the benefit of the company, not the listener who is steered towards cheap content through made-up genres. And personalised curation is just a way that Spotify gets listeners to do their job for them: listeners essentially compile their own data. Furthermore, Spotify shares this data with others to create online profiles to be used in everything from job applications to more targeted marketing. Pelly is concerned about the ways that Spotify, along with other tech companies, wants to and is invading your privacy.

Ten years ago, Spotify decided that a way to make more money was to pay less royalties to record labels (who are meant to pass them on to artists). They did this by commissioning music from music production companies who made music through session musicians, labelling these ‘ghost artists’ on Spotify with fake names and biographies. This was the equivalent of changing a farmers’ market to a McDonald’s – or perhaps selling McDonald’s food at a farmers’ market. The ‘ghost artists’ were directed to churn out repetitive, simple tunes – muzak – that Spotify flooded their chill playlists with.

It gets weird: Spotify removed thousands of songs at one point because the companies making this music began using AI (trained on the products of real musicians who weren’t compensated) to make these tunes and then created bots to repeatedly listen to the music to ramp up the number of streams. This anomaly nevertheless points to something about the system.

Spotify encourages musicians to tailor their music to the audience, and to churn out music to keep listeners engaged, rather than embark on the older process of thoughtfully putting an album together over a long period. ‘Challenging’ music is not rewarded. Artists who play the Spotify game, like Billie Eilish, can make a lot of money, but most artists get next to nothing, and the system is not much better than piracy. The creation of playlists is weighted towards the big record companies, and promotion for lesser artists is promised only if they lower their already minimal returns. Since consumers are now used to cheap streaming, and Spotify has cornered the market, for independent artists, there aren’t a lot of other options, though Pelly does report, at the end of her book, on some mildly hopeful developments. (She also says there are no clear and easy answers.)

One could argue that much popular music was never capital-A Art and pop songs give listeners what they want. But the problem with the easy availability of all this music is that for musicians, the cost of a streamed song does not reflect the cost of creating the music. For listeners, the Spotify experience is further individualising us and entangling us in the web of big tech, and the result of being spoilt for choice is that we don’t place much value on the music.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.